On Nick Mulder’s new history of the interwar period.

“(W)e tried, just as the Germans tried, to make our enemies unwilling that their children should be born; we tried to bring about such a state of destitution that those children, if born at all, should be born dead.” – William Arnold-Forster, a British blockade administrator and ardent internationalist, reflecting on the World War I blockade of Germany.

Sanctions are all over the news right now. Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Russia come to mind.

Against this backdrop, Nicholas Mulder’s new book, The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (Yale), is essential reading, not just for historians.

Btw, Nick (@njtmulder) is also a great follow on twitter and, full disclosure, a close friend. What follows isn’t so much a critique as an appreciation. I’ve seen this project in many stages and I am really delighted to see what Nick has pulled off.

If you don’t trust me 😉 check out the write ups by Lawrence Freedman in Foreign Affairs and Paul Kennedy in WSJ or Henry Farrell on twitter. As Henry says:“This is going to be a debate changing book.”

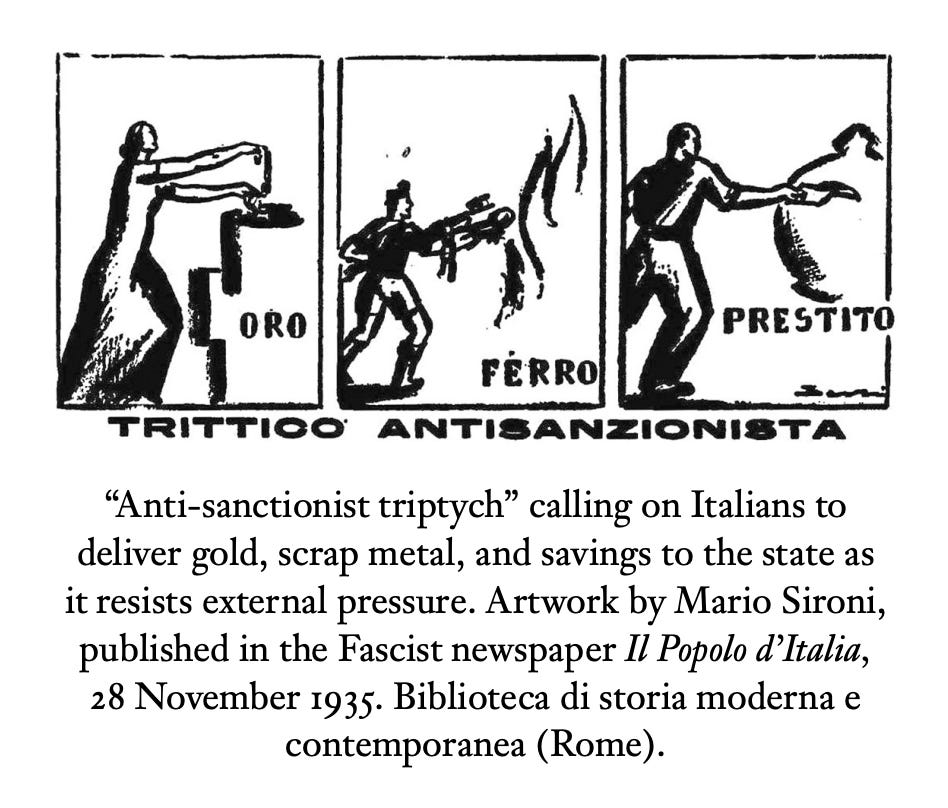

If you have any interest in political economy, international relations, interwar history, if you liked Deluge or Wages of Destruction, you should check Mulder’s book out. It’s highly original, powerfully argued, wonderfully well-written and elegantly produced by Yale UP, with lots of excellent illustrations.

As I want to emphasize in this newsletter, it ought to appeal to those interested in the history of neoliberalism and liberal economic ideas too.

One way of reading Mulder is to see his book as offering a history of another “new liberalism” to set alongside Quinn Slobodian’s rightly-celeberated history of neoliberalism, Globalists. If Slobodian showed how neoliberalism was born in central Europe out of the desire to defend capitalism against the collapse of Empire and the emergence of economic nationalism, Mulder shows us the other side of the dialectic – how aggressive nationalist drives for autarky were fueled by another new liberalism’s exorbitant schemes for weaponizing the world economy.

The crucial point to emphasize is that following World War I, the economic blockade was seen as a truly devastating weapon. Until the advent of giant fleets of heavy bombers, and atomic weapons, the blockade was a far more plausible means for striking against the enemy’s home front than airpower. All told, in World War I, aerial bombardment (by Zeppelin for example) killed perhaps two thousand civilians, the majority of them in Britain. By contrast, the Allied economic blockade, unarguably, killed hundred of thousands of civilians on the side of the Central Powers. Mulder gives 300-400,000 as a plausible figure. In the Middle East, 500,000 civilians died in blockade-induced famines.

As Mulder remarks:

Before World War II these hundreds of thousands of deaths by economic isolation were the chief man-made cause of civilian death in twentieth-century conflict

Economic warfare was a mighty weapon and the victor powers in World War I saw as it as the obvious tool through which the League of Nations would deter war and enforce peace. It was liberalism’s ultimate weapon.

This should lead to a fundamental revision of our view of the entire League project. As Mulder puts it:

The collapse of the global political and economic order in the 1930s and the outbreak of a second world war have made it easy to dismiss the League as a utopian enterprise. Many at the time and since concluded that the peace treaties were fatally flawed and that the new international institution was too weak to preserve stability. Their view, still widespread today, is that the League lacked the means to bring disturbers of peace to heel. But this was not the view of its founders, who believed they had equipped the organization with a new and powerful kind of coercive instrument for the modern world. That instrument was sanctions, described in 1919 by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson as “something more tremendous than war”: the threat was “an absolute isolation . . . that brings a nation to its senses just as suffocation removes from the individual all inclinations to fight. . . . Apply this 2 Introduction economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It is a terrible remedy. It does not cost a life outside of the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon that nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.”1 In the first decade of the League’s existence, the instrument described by Wilson was often referred to in English as “the economic weapon.”

In retrospect the economic weapon reveals itself as one of liberal internationalism’s most enduring innovations of the twentieth century and a key to understanding its paradoxical approach to war and peace.

The German legal theorist and later advisor to the Nazis, Carl Schmitt, is famous for arguing that the League and its economic weapon blurred the boundary between war and peace. The League veiled the iron first of Anglo-American hegemony in a velvet glove of commerce and morality. On the general point, Schmitt was not wrong. But, as Mulder makes clear, Schmitt was neither particularly original, nor particularly precise in making his case.

The late 1920s were marked not by a sinister liberal plot orchestrated through the League, but by a hybrid condition of transition from one political-legal order to another. The new “public” system of collective security and League sanctions was chafing against an older “private” system of limited war, neutrality, and humanitarian law. It was precisely the uneasy coexistence of these two paradigms between 1927 and 1931 that made the period’s politics so disorienting. But this was not, as Schmitt suggested, a struggle between liberalism and some anti- or non-liberal alternative; in his preference for the older separationist system, Schmitt was in fact aligned with many classical liberals and future neoliberals.98 The divide between sanctionism and neutrality expressed not a conflict between liberalism and its enemies but a clash between opposing paradigms within liberalism itself.

Certainly the deployment of economic sanctions was tied up with a more general mutation of liberalism. In the interwar period a new strain of liberalism emerged. Its preeeminent domain were the fields of technical governance, the administrative apparatus of international law, expert diplomacy, logistics and applied economics.

Long-standing traditions, such as the protection of neutrality, civilian noncombatants, private property, and food supplies, were eroded or circumscribed. Meanwhile, new practices, such as police action against aggressor states and logistical assistance to the victims of aggression, arose. All of this amounted to a major and complex transformation of the international system. Today, economic sanctions are generally regarded as an alternative to war. But for most people in the interwar period, the economic weapon was the very essence of total war.

If populist, democratic economic nationalism was one of neoliberalism’s enemies, this other new liberalism, was another. Economic sanctions were the weapons of experts.

As Mulder remarks, sanctions and blockade were a new kind of war, an expert, bureaucratic war.

Sanctions were attractive not just because of their potential power, but also because they were easy to use for their handlers. Their coercive power was administered not out of the cockpit of a bomber or through the breech of a cannon but from behind a mahogany desk. Sanctions, an American commentator argued, were special because their “field of operations is not a visible terrain; but a force is exerted just the same.”

If, as Keynes remarked in the famous cameo at the beginning of the Economic Consequences of the Peace, in the halcyon days before 1914 an English gentleman could, from the comfort of his bed, order up the produce of the world. That same English gentleman, wielding the heft of the City of London and the global reach of the Royal Navy, could, later that same day, deny those same products to the civilian population of any enemy power.

Nor were interwar liberals hy about describing the awesome effects of this new means of coercion. As Mulder astutely points out, talking up the devastating effects of economic warfare was part of the deterrence strategy.

A nation put under comprehensive blockade was on the road to social collapse. The experience of material isolation left its mark on society for decades afterward, as the effects of poor health, hunger, and malnutrition were transmitted to unborn generations. Weakened mothers gave birth to underdeveloped and stunted children.4 The economic weapon thereby cast a long-lasting socio-economic and biological shadow over targeted societies, not unlike radioactive fallout.

None of this was a shameful secret. Nor was it, for the advocates of League sanctions, an argument against their favorite new weapon. Comprehensive devastation of the home front was the point. Crimes against peace were the ultimate crime in international law. Economic sanctions were the appropriate answer.

The inescapable question is, did the threat of sanctions work?

Against smaller states, Mulder argues, sanctions could claim a degree of effectiveness. They helped to deter aggression and make arbitration seem more attractive. Against the backdrop of the 1920s, when the threats of the world economy were tightly woven and the future looked bright, the elites of Germany, Italy and Japan also saw their interests aligned with the West. But, as Mulder argues in a brilliant concluding section, once the Great Depression struck, the League regime unfolded a perverse logic. The threat of economic sanctions justified moves towards radical economic nationalism, programs of autarky and ultimately warlike aggression in pursuit of the kind of Lebensraum that could withstand the global economic might of the United States and the French and British Empires.

It was not by accident that Hitler’s Germany launched its Four Year Plan in 1936, in the wake of the application of League sanctions to Mussolini.

To both Berlin and Tokyo, territorial expansion became a way to enhance self-reliance, mobilize popular support, and retain strategic independence. Conquest appeared as an avenue of escape from the anxiety of living under the Damoclean sword of international blockade. Over time, the seeming inevitability of economic war prompted both Adolf Hitler and the Japanese leadership to secure resources by any means available. The internationalist search for more effective sanctions and the ultra-nationalist search for autarky thereby became locked in an escalatory spiral

The result was paradoxical, in one particularly brilliant passage Mulder quotes Luigi Einaudi, the famous Italian liberal economist from an article of 1937, in which Einaudi pointed out that contemporary usage conflated two different notions, “autarchy” and “autarky.”

The ancient Greek term autarchy, he pointed out, derived from the words αὐτός (self) and ἀρχή (rule). It had been used by Stoic philosophers to denote independence, a political state of self-rule, or a psychological condition of self-command. This concept was distinct from autarky, which combined αὐτός with the verb ἀρκέω (to suffice) and entailed material self-sufficiency

The insurgent states of the 1930s were able to attain neither.

Since none of these three countries—united after 1936–1937 through the Anti-Comintern Pact—was self-sufficient in crucial raw materials, their search for immunity against blockade strengthened their inclination toward territorial conquest. As their strategic ambitions grew, the threat and application of new sanctions only increased the urgency of securing resources at all costs. Economic pressure, meant to restrain aggressive expansion, now began to accelerate it.

And material shortage, all too easily, could be reinterpreted through the lens of racial ideology. For Göring it was a small step from remarking that 1914–1918 Germany had possessed “insufficient counter-measures”, to warning industrialists: “Imagine only that we would no longer obtain any Swedish iron ore, if it should fall into Jewish hands!” As I argued in Wages of Destruction, the culmination of this politico-ideological-economic-grand-strategic maelstrom was Hitler’s infamous address to the Reichstag on 30 January 1939, where he linked Germany’s economic difficulties, shortages of hard currency, the prospect of world war (with the United States) to a lethal threat to European Jewry.

As Mulder remarks:

In this pattern of “temporal claustrophobia,” desperate decisions for conquest brought into being the economic pressure that the Nazis were trying to escape, causing greater problems of supply that propelled the regime forward to its inevitable defeat and destruction.138

But the chain of action and reaction did not stop there. The drive to war on the part of the insurgents, in turn, triggered a further twist in the dialectic.

On top of the punitive deployment of the economic weapon, the Allied bloc turned back in 1939 to the idea of the “positive economic weapon” – concerted economic cooperation and mutual aid, as a crucial factor in organizing world power. This, for Mulder, is the road not taken in the interwar period. Not the threat of devastation, but the promise of large-scale economic and financial support for those under threat of aggression. The giant Lend Lease program of 1941 was the logical result of that belated realization.

Whether it worked or not in deterring war, Mulder leaves us in no doubt that the emergence of the economic in World War I shaped the modern world down to the present day. The continuities to the present, however, are not straight forward.

Mulder’s brilliant book ends with an appropriately ironic historical reflection.

By 1945, the material conditions existed in which the idea of ending aggression could acquire real teeth. For the first time, a sizable group of states was able and willing not just to chastise transgressors, but also to organize resources for solidarity. At its head stood the United States, the workshop of the world, its main aid provider, and the rising sanctions wielding state. In light of its interwar opposition to sanctionism, the U.S. emergence in this role was a remarkable historical reversal.168

On its face, the new world order meant a complete defeat for any notion of neutrality.

As the British interwar liberal, Kenworthy remarked in 1944:

“in these days, first of all of totalitarian war, and then of war against robber States such as Germany and Japan, the conception of neutrality has largely disappeared. You cannot have neutrals any longer in the old sense in the future, and we shall not have won this war in the political sense if we do not succeed in establishing a system after the war by which in the case of a new aggression or new outburst of lawlessness no neutrals remain.”164 The classical era of neutrality had indeed ended, and with it, the way that war and peace had functioned in the international order.165 In the coming era of superpower conflict, the end of neutrality put the independence of small countries back into question. Economic warfare created, in the words of the blockade’s main historian, “a world fit, or fit only, for belligerents to live in.”166

But in the wake of the horrors of strategic bombing, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in the new regime of the United Nations, the original cognitive shock of the 1920s was largely forgotten. The debates of the interwar period were dismissed or denied. The UN embargoes and Cold War–era sanctions came to be seen as a

benign alternative to atomic war, an enlightened overcoming of the past. Yet the economic weapon was an interwar creation that was carried over into the postwar world by power politics. What had changed after 1945 was that a novel group of nations had come to agree on a new institutional framework for its use. The history of sanctions also changed in character. Between the wars it had been a predominantly Euro-American affair in which the non-Western world was peripherally involved. For the rest of the century, it would be a global practice in which American power was dominant, while the socialist Eastern bloc and newly independent states in the Third World both resisted and appropriated the tools of economic pressure.

What overall lessons should we draw? I will leave you to buy and read the book to find out!

You will not be disappointed. It is a fascinating work. Mulder has written more than a technical monograph. By way of the economic weapon he offers us a new vision of the first half of the twentieth century.

***

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. Voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, pick one of the options here.