Earlier this week, Mohamed El-Erian was lost for words. As he wrote in the FT:

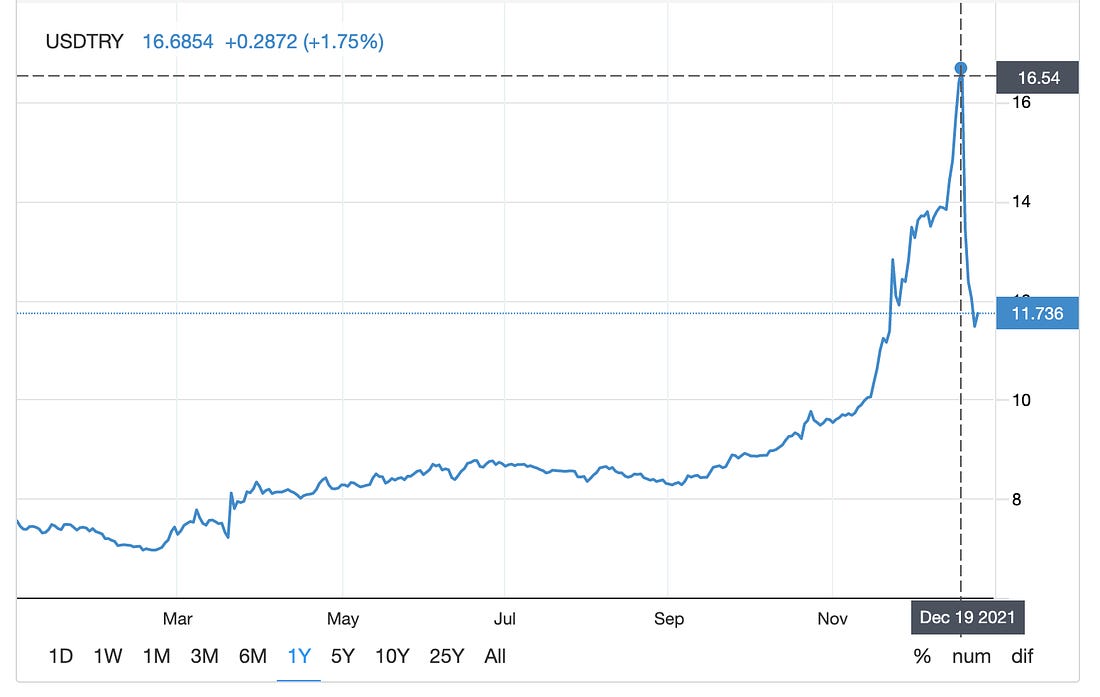

It is hard to put into words how disorderly the Turkish currency markets had become by Monday afternoon. The lira had weakened to beyond TL18 per US dollar, constituting a halving of its value in just two months.

It was the low point in the staggering run on the Turkish Lira that began in earnest in September.

***

Turkey’s financial crisis has thrown into turmoil a country that is pivotal to the Eastern Mediterranean, Western Asia and forms the boundary between the Middle East and Europe.

In recent decades, Turkey with its population of 84 million has been hailed variously as a great success story, a future home of Muslim Democracy, a democratic backslider and quasi-authoritarian regime.

Its population and relative economic success gives Turkey heft. Erdogan’s government is a power political player in the Caucasus (backing Azerbaijan v. Armenia), Syria, Iraq and Libya, to name just the most obvious theaters of its foreign policy. It also holds the key to the European refugee situation.

In an import-dependent economy, the halving of the exchange rate in a matter of months delivers a dramatic shock, driving up the price of essentials and unleashing inflation. Inflation number themselves become the object of bitter argument.

According to Al-Monitor: “Turkey’s monthly consumer inflation is expected to hit a staggering 15% in December and bring the annual rate to at least 35%. The Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) is due to release the official figures Jan. 3.” But accessing the statistical agency can be difficult for opposition politicians.

Gates locked! Turkey statistics agency doesn’t allow main opp leader @kilicdarogluk in who wanted to pay a visit following the latest official inflation numbers (21.31% for Nov) which opp claims shd be much higher pic.twitter.com/2YriU0A2PY

— Selin Girit (@selingirit) December 3, 2021

On the other hand, Turks who support embattled President Erdogan celebrated the rebound of the lira against the dollar earlier in the week by demonstratively destroying the American currency.

Dolar kıyması yapan zihniyet… Bu cehaleti ancak Erdoğan yönlendirebiliyor. Geçmiş olsun hepimize… pic.twitter.com/fBi39XsSDN

— Maaz İbrahimoğlu (@maazibrahimoglu) December 22, 2021

Behind the scenes, billions in private deposits have shifted from the unstable Lira to foreign currency deposits. The government is now trying to tempt them back.

Those with funds to move are the lucky ones. Turkey is a middle-income country, millions of citizens scrape by at very low income levels. As Middle East Eye reports: “bread prices have shot up by 25 percent in the past month alone, creating long lines of people outside subsidised bakeries owned by local municipalities. Flour prices have jumped by 300 percent in a year, while other basic items such as milk and cheese have seen a 47 percent price rise due to increasing costs.”

***

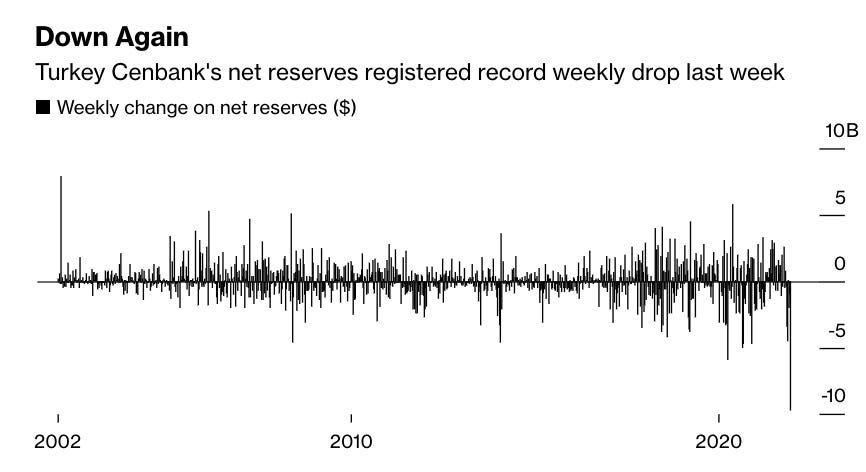

Though the Turkish central bank is secretive about its interventions, it is clear that it has been trying to stem the collapse in the Lira by selling any dollars it can get it hands on. The result is a crazy escalation in the central bank balance sheet, as the bank borrows funds to pump into the markets.

The Turkish central bank doesn’t like doing this in public or in daylight, so it has taken to making unannounced interventions overnight. For those Turks who have bet the other way, on a continuing depreciation, the sudden reversal is itself a disaster.

Source: Bloomberg

Once upon a time Brad Setser would have been filling us in on the movements in Turkey’s balance sheets. But Brad is now with US Treasury. In his stead, the brilliant Daniela Gabor has stepped up with this fantastic thread.

The one thing that the central bank is not doing is raising interest rates. This is at the heart of the entire crisis. President Erdogan does not like independent central bankers. In March 2021 he replaced Naci Ağbal who was installed in November 2020 in the midst of a previous wave of currency depreciation and was credited with pursuing a more orthodox course with Şahap Kavcıoğlu a former MP for Erdogan’s AKP.

On direct orders from President Erdogan, since August, the Turkish Central Bank has cut its policy rate by 500 basis points, from 19 percent to 14 percent. It is that remarkable decision, contrary to pressure in global markets and global economic opinion that has set the stage for the current crisis.

It is a remarkable escalation of Erdogan’s long-standing struggle with finance and capital markets. For older Turks, a crisis this severe awakens bitter memories of earlier historical moments. See this series of interviews by Middle East Eye.

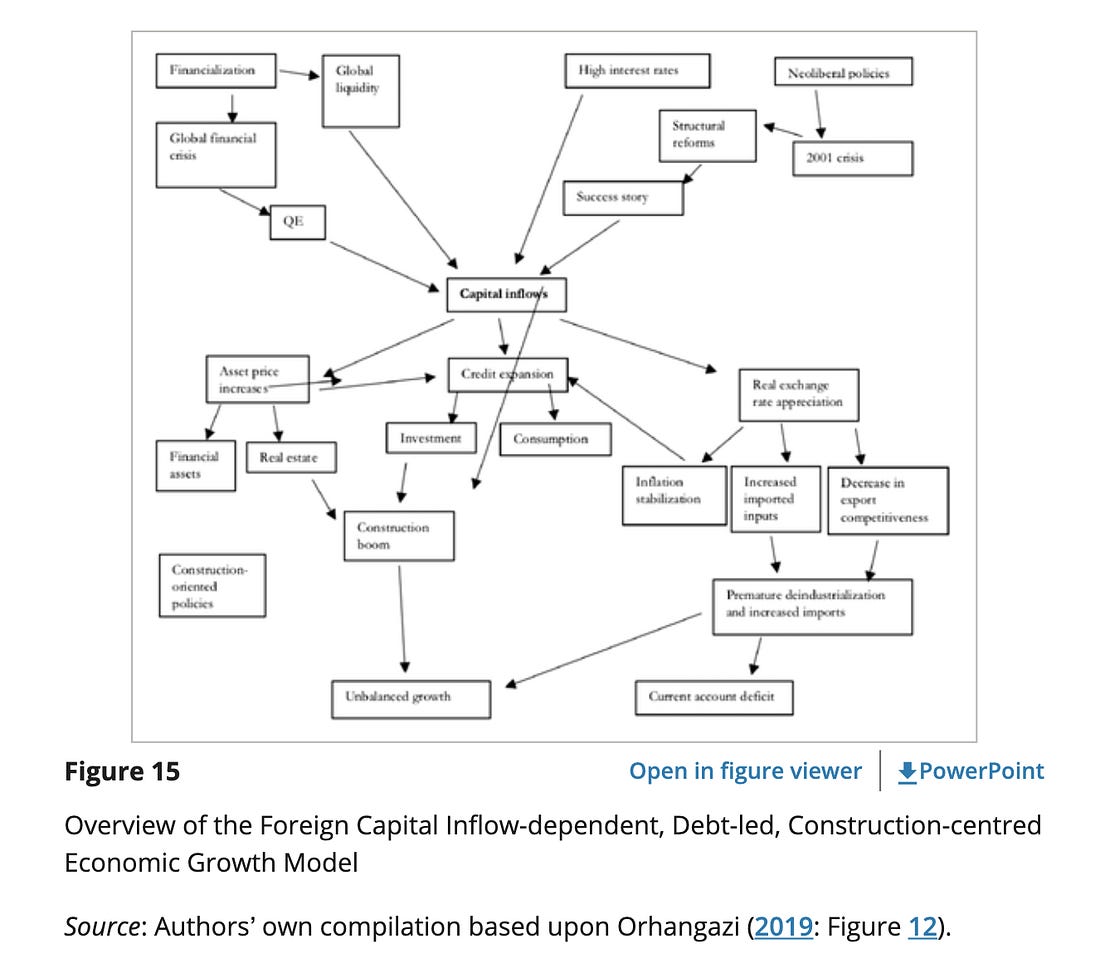

Since the early 2000s Turkey has relied heavily on foreign borrowing (mainly by the private sector) to finance large current account deficits brought on by rapid growth. As Dani Rodrik told the FT:

Erdogan had ridden a wave of capital inflows that were attracted to Turkey by slightly higher interest rate margins. “One of the myths of financial globalisation is that it enforces macro[economic] discipline,” Rodrik said, suggesting that financial markets would ensure countries ran credible and sustainable policies that attracted foreign cash. “In Turkey, it was the opposite. Turkey’s economic experiment ran much longer than it should have, thanks to the more elastic supply of finance. The economic costs will be larger as a result.”

It is not the first time that Turkey has come under pressure. But the shock of 2021 is exceptional.

What is Erdogan’s game?

***

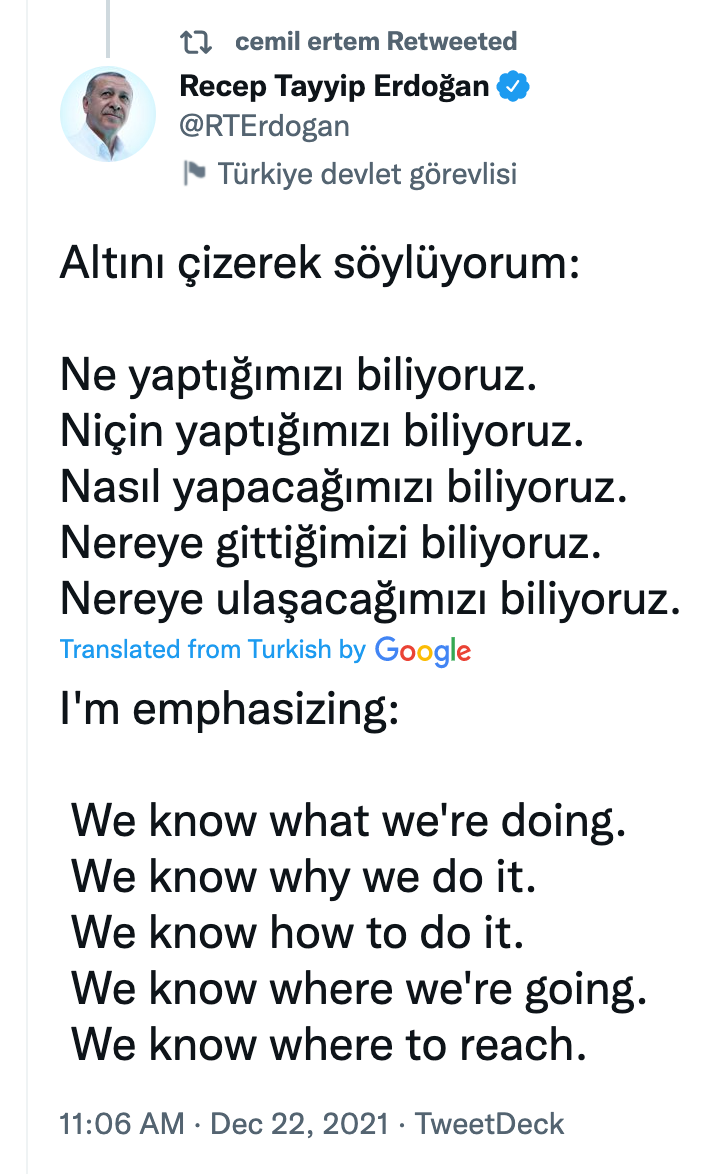

Erdogan has long cultivated an economic ideology that consists of a brew of convenient fragments of Muslim doctrine, productivism, hostility towards outside pressure. He is prone to associating any critics with external threats. As he made clear in recent weeks:

“Of course we know that price rises are causing problems in the daily lives of our people. Of course we are aware of the volatility in the exchange rate, the instability in prices and the uncertainty this creates,” he said. “But we will resist these just as we resisted tutelage, terrorist organisations, putschists and global power barons. I am telling you, there is no going back.” He attacked Tusiad, the country’s largest business association, which on Saturday urged the government to return to the “established rules of economic science” to restore stability and prevent further damage to business and the public. “Hey, Tusiad and your offspring,” he said. “I’m telling you, you have one job: investment, production, employment, growth . . . You cannot interfere in what we are doing.” The previous day, the head of Turkey’s Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges (TOBB), which represents small and medium-sized businesses and has in the past been supportive of Erdogan’s approach, warned that the financial turbulence was “worrying and negatively affecting many of our companies”. Rifat Hisarciklioglu, TOBB’s president, called on the government to take “urgent steps” to stabilise the markets and restore a more predictable environment for business. “Don’t expect anything else from me,” he said in a televised speech on Sunday night. “As a Muslim, I will continue to do whatever the religious decrees require,” he added, in a reference to prohibitions in Islam on usury.

Warring with Turkey’s secular business interests is now a key device through which Erdogan rallies his electoral troops.

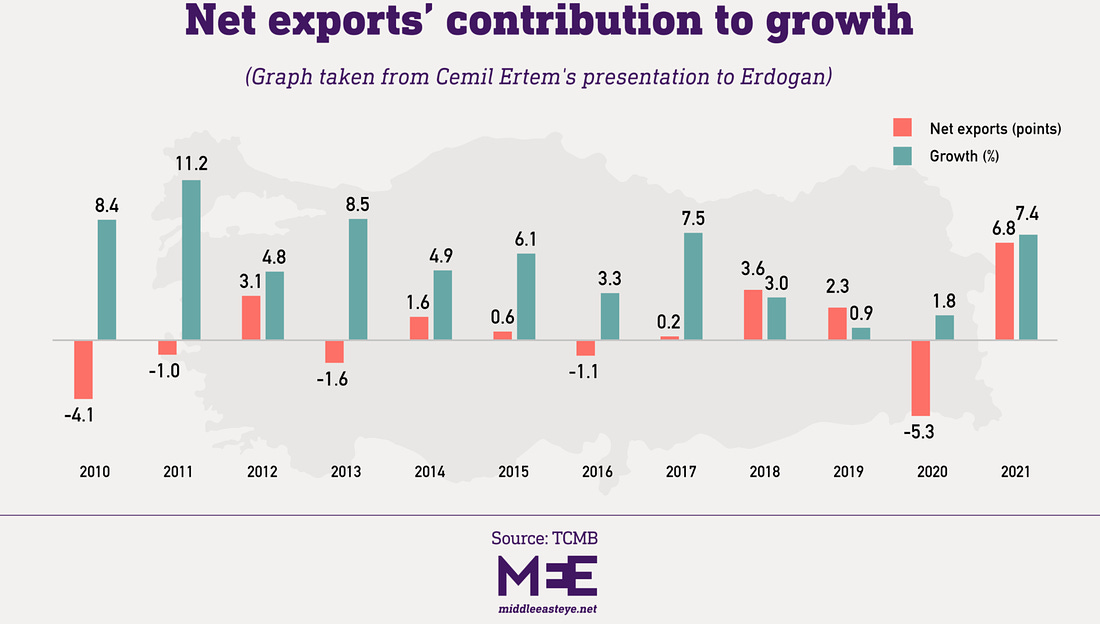

He is egged on by advisors such as Cemil Ertem who systematically promotes the idea of politico-economic autonomy. Middle East Eye has gain accessed to a briefing paper prepared by Ertem, titled “The New Economic Model: Reasons and its Benefits” that may well be exerting a significant influence at this moment.

The main message given by Ertem’s presentation is economic independence. Over and over, he emphasises that it is impossible to be economically independent while carrying out a financial policy based on high interest rates or International Monetary Fund recommendations. Ertem asserts that a policy of high interest rates has triggered a vicious circle of low exports, lower employment, high imports, growing external debt and a country with an external dependence, which again requires higher interest rates, completing a full circle. “As a result, the country is posting a high current account deficit and depending on short-term hot money inflows and raising the external debt,” he says in the presentation. “This economic model, due to its external dependency, is laying [the] ground for economic attacks.” The chief economic adviser says his new model, based on lower interest rates, will increase exports and decrease imports, leading to a current account surplus and higher growth with high employment. He believes it will make Turkish exports more competitive with a depreciated lira. “We will incentivise foreign direct investments instead of short-term hot money inflows, and stabilise the foreign finances,” Ertem says. “And that’s how we will become a stronger country that is protected from the external financial shocks.”

If Erdogan were seriously introspective he would see that the growth model of recent decades that has sustained his own regime looks something like this one described by Özgür Orhangazi,A. Erinç Yeldan in Development and Change (2021).

It does indeed systematically promote growth through construction rather than manufacturing, agriculture and exports. But rather than these structural elements, Ertem in his advice to Erdogan apparently stresses the political and geopolitical dimensions of dependence.

Providing examples of when the lira has depreciated previously – such as during the 2013 Gezi Park protests, the 2016 coup attempt, US sanctions in 2018 over a pastor’s arrest, and in 2019 due to a Turkish military operation in Syria – Ertem argues that geopolitical developments can be used as a tool to undermine economies based on foreign dependency.

The political logic may be important because it helps to explain timing. After all, what needs to be explained is why now? Erdogan faces difficult elections in 2023 if not earlier. The geopolitical environment is difficult. The Biden administration is not friendly. The disintegration of liberal norms in economic policy is widespread. The IMF is no longer the force that it was when it brought Turkey to heal in 2001. This interview with Aybars Yanik in Birikim is interesting on this point (Google translate).

Since the local elections of 2019 Erdogan has been struggling to keep his grip on the Turkish electorate. Does the policy shift of 2021 signal a bid for redemption by way of a new strategy of “running the economy hot”.

Is the economic logic of Erdogan’s wager, as Policy Tensor suggests, to achieve a “permanent devaluation of the lira, effectively lowering unit labor costs in Turkey thereby making Turkish workers more competitive.”

Certainly the devaluations of recent years have had an effect. “exports jumped 33 percent in November, reaching $21.5bn, while the current account posted a $3.16bn surplus for October. Unemployment has also decreased, by about two percentage points, from 13.1 percent to 11.2 percent in October year-on-year. GDP grew by seven percent in the third quarter of 2021.”

But can this be sustained? If domestic inflation keeps tracks with devaluation then there is no gain in competitiveness.

With import prices soaring, the economic circumstances threaten to crush domestic demand; a recent 50 per cent rise in the minimum wage will wipe out the cost advantages of the currency depreciation, according to Tim Ash of BlueBay Asset Management. “If [Erdogan] had managed to hold [the line] when there were 10 lira to the [US] dollar, maybe they had a chance but, now inflation is out of the bag, the competitive advantage will go out of the window and we are in a devaluation inflation spiral,” Ash said.

Furthermore, for devaluation to yield dramatic benefits would require an industrial policy to back it up. The people that the FT talked to, doubt that Erdogan has any such plan.

In recent months, as Erdogan launched another easing cycle, he has reportedly cited China’s economic transformation in the wake of 1978 reforms as evidence that his model would bear fruit. But Ali Akkemik, an expert on the economies of both China and Turkey at Japan’s Yamaguchi University, said that while it was true that Beijing had devalued its currency in the 1980s and 1990s, it had implemented a clear “industrial vision” that was crucial in its transformation into the world’s second-largest economy over the course of several decades. “Turkey doesn’t have any clearly defined industrial policy,” he warned. “We don’t know what industry they’re trying to promote.” A London-based banker with expertise on both economies who asked not to be named put it more bluntly. “It is economically crazy to think that a country can build an export-oriented economy simply on the back of a trashed currency,” he said. “If that were the case, Zimbabwe would be a tech superpower.”

Nor is the political logic of Erdogan’s maneuvering as obvious as it might seem. As Atilla Yesilada, an analyst at the consultancy GlobalSource Partners, remarked: “this is not a policy that benefits any identifiable constituency, including his family . . . or his cronies”.

Some businesses are gaining from the slide in the currency. “Most of the companies listed on the Borsa Istanbul are benefiting from the weak lira,” said Selim Kunter, an equities analyst at the Istanbul-based Ak Yatirim. He pointed to publicly listed airlines, defence groups, carmakers and chemicals producers as companies that enjoy foreign currency-denominated revenues and Turkish lira-denominated staffing costs. …. “Erdogan is prioritising exporters over households,” said Jason Tuvey of the consultancy Capital Economics. “If you think about his support base, it doesn’t really make sense at all.” Many big exporters have also been critical of the currency volatility, which they say makes it difficult to price their products and plan ahead. Tusiad, a group representing large industrial companies that account for 85 per cent of Turkey’s foreign trade, excluding energy, has warned that what the business world needs most is stability. Musiad, a business association with close links to the ruling party, recently added its voice to the disquiet in a rare critique of the president’s approach. “A businessman needs to know what the exchange rate will be in two to three months’ time and how much it will rise,”

Even the construction sector, the usual beneficiary of AKP largesse has begun to complain. The high cost of raw materials is hurting them.

Erdogan simply “doesn’t have a game plan”, Yesilada said, pointing to the fact that Turkish authorities have spent several billion dollars defending the lira in recent weeks while simultaneously praising the virtues of a cheap currency. “We can discuss it for hours. None of it makes sense,” said Yesilada. “There isn’t any logic.”

***

Over the course of this week there has been a period of stabilization. The exchange rate was oversold. As the IIF’s Robin Brooks insists, the lira was spectacularly undervalued relative to its fair value. Turkey’s hard currency bonds still enjoy considerable market support.

To achieve stabilization, Erdogan’s government has launched an innovative scheme to drive deposits back into lira bank accounts. As the Middle East Eye explains:

Turk Dolar: The new tool, labelled the “Turkish dollar” by some on social media, offers a solution to this problem: if investors convert their foreign currencies into lira and deposit them in a savings account with a certain term of maturity, Turkey’s treasury guarantees that it will get the same return as forex markets. And if the forex markets drop below the official interest rates, the investor will still get an official interest rate return.

The result has been to produce a significant lira rally. But it also risks having perverse effects.

“In effect, all this just increases dollarisation, as the deposit base either is in FX or now FX linked,” Tim Ash, a senior strategist at London-based BlueBay Asset Management, said. “And the public purse picks up the bill. Arguably dollarisation shifts from the private to public sector.”

A similar scheme adopted in the 1970s helped to fuel a disastrous inflation. “Baris Soydan, a prominent Turkish journalist, said in a column on Tuesday that the idea was initially brought back by officials in 2018, but they quickly abandoned it because of possible and deep ramifications on the treasury.”

El Erian in the FT opined that it may buy Ankara some time. But what it will need to do is precisely what Erdogan is not committed to doing i.e. “

The government can help this process by credibly signalling that the latest measures are not an end in themselves but rather a bridge to a more comprehensive set of policies. This would include explicit rate hikes by the central bank which, at this point, are still necessary but no longer sufficient. Turkey will also need to seek other internal anchors, such as a tightening of fiscal policy, and perhaps also external ones, such as agreement on an IMF programme that provides both funding and external validations. All this will need to be done while avoiding the understandable temptation of capital controls that would undermine a historically powerful, and still impactful open growth model that, both economically and financially, exploits Turkey’s many “competitive edges”.”

Rather than beating about the bush, Barry Eichengreen simply concludes that Turkey is now en route to hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation, of course, has two ingredients. First, money creation that fuels inflation. Second, and critically, inflation that fuels money creation. Erdoğan’s deposit guarantee adds this second element. The Turkish Treasury is not going to be able to sell bonds to finance its deposit scheme. It will have to rely on central bank credit … Although there are alternatives to the high-inflation scenario, none is happy.

***

The answer from Erdogan himself?