Making sense of Build Back Better

NB: As you will see from the below, this newsletter was being edited literally as Joe Manchin was killing Build Back Better on Fox TV. Gutted. Trying to figure out what comes next. Pinwheel for now …. pinwheel in the darkest colors.

Back in November, a good friend from the climate community (you know who you are) sat me down and explained how he saw the negotiations over Biden’s Build Back Better infrastructure and welfare package working. Out of that came the slow-cooked piece that appeared in the New Statesman last week.

In the New Statesman I attempt a broader assessment at what is at stake in Build Back Better. I want to focus here on the climate part which was the original motivation for the piece.

In the foreground was the haggling with the centrist Democrats Joe Manchin and Kirsten Sinema. With them it was a matter of pork, of “pay-fors”, of fiscal evaluation by the Congressional Budget Office – conventional fiscal politics in other words. It was tortuous and demoralizing to see Biden’s undersized investment program being further whittled down.

To address climate, the dereliction of infrastructure and America’s many social ills, let alone the “China challenge”, the investment program would have needed to have been hundreds of billions more per annum. For a country of America’s resources, the railway and EV-charger components are laughable. Defense spending in excess of $760 billion per annum puts everything else. This is what America is capable of if its political class actually agrees.

But for all the gloom, there was a glint of enthusiasm in my friend’s eye. Behind the scenes the people pushing Build Back Better had a secret weapon – the modeling teams working the numbers for CO2-emissions.

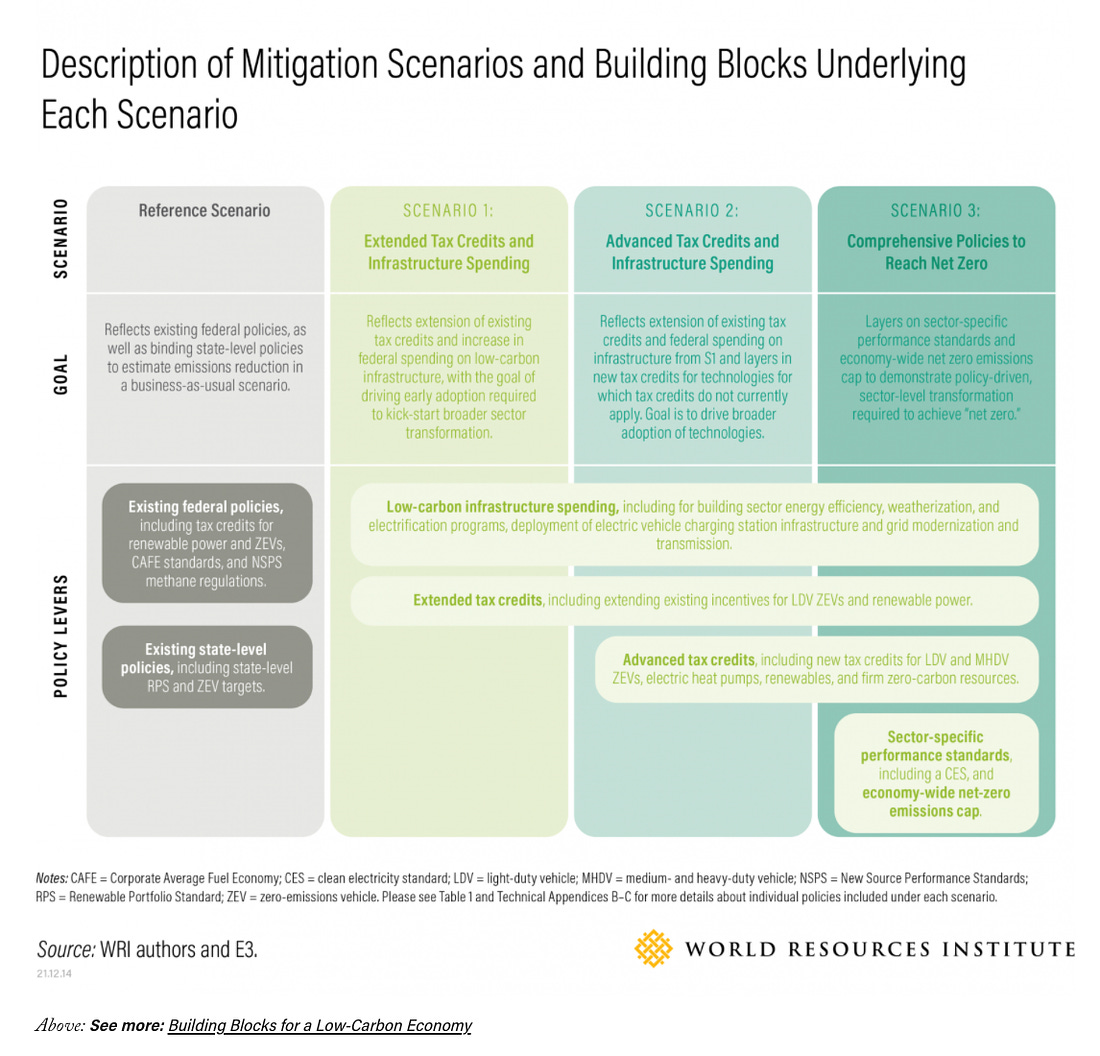

There were several of these teams. Another interlocutor named three that were particularly influential: Rhodium, Energy Innovation and the Princeton Net Zero project. WRI and E3 have also been working on the problem. There is talk of a group of staffers around Senator Chuck Schumer. When Schumer refers to “the best available data from a wide range of organizations that specialize in policy analysis”, he is, presumably, referring to this network.

If there are other key groups involved that I have not mentioned, I apologize. I would love to hear about their work and to assemble a map of this complex of modeling and analytic project. A project for 2022.

I am sure there is a lot more one could say about the different models they use and their implications. But I want to focus here on the political implications.

What they have been doing, through all the Congressional haggling, is to score each of the revised versions of the bill, as they come down from Capitol Hill, with a view to keeping the overall package in line with the climate objectives of the Biden administration. Above all this has involved replacing sticks with carrots. When Manchin strikes a penalty you add in an inducement to speed up the EV-transition.

The upshot, as the WRI has most recently confirmed, is that so long as the basic provisions of Build Back Better make it through the Senate, there is enough there to give the Biden administration a fighting chance of keeping the US on course for a 50 percent emissions reduction relative to 2005 by 2030.

Energy and CO2 emissions modeling have helped to guide the rearguard action. In the context of the broader discussions about the emergence of a new paradigm in economic policy in 2021, this seems to me to be a significant point.

Often the tendency is to assume that new concepts and ideas in economic policy take the stage when a progressive policy program is on the front foot. That, I think, was the tone of the discussion earlier in the year that accompanied the inauguration of the Biden administration. Indeed, the hope was that with new ideas one might actually gain political momentum. Novelty and innovation build energy and momentum. Its a caricature, perhaps, but I think that was the vibe around the association between MMT and the Green New Deal.

What we are seeing in the context of the “Build Back Better”-fight is a different theory of change. New types of knowledge are being brought to bear on the policy-process, but as part of a rearguard action, to save what can be saved.

The scoring of fiscal policy on the basis of CO2 emissions rather than votes in Congress, impact on the Federal deficit, output gaps or GDP, strikes me as a remarkable innovation.

The idea of doing a green stimulus has been around at least since 2007 and the birth of the first Green New Deal. A lot of modeling has been done on the energy transition. But this is something different: blow by blow negotiation of fiscal policy guided by CO2 scoring with a view to achieving a particular target for emissions reductions within a given timeframe. This is much closer to output gap calculations, or conventional fiscal rules, but with CO2 rather than percentages of GDP as the basic metric.

I’m going to call this a historic first.

I think the idea came to me because I had been teaching a segment in my “Capitalism and Democracy” class on the so-called “Keynesian revolution in government” during the 1940s. One of the key issues in that debate about British and American government is: when does fiscal policy become subordinated to a clearly macroeconomic logic?

The historiography is quite technical and seems to have died down on the UK side about thirty years ago. One good summary for the UK side is by Rollings (1988). For the US William J. Barber’s Design within Disorder is a useful overview.

It is parochial in its focus on the Anglosphere. Planners in Goering’s Four Year Plan were doing output gap estimates at the latest by 1938.

It should not be confused with the broader debate about the “invention of the economy” as an object of government, which to my mind predates the “Keynesian revolution in government” by at least two decades.

But there is no doubt, that as far as fiscal policy in the US and the UK is concerned, the 1940s brought major institutional and conceptual changes. And what is striking, is that the Keynesian revolution in government, particularly in the UK, was innovation on the defensive.

One might think that a Keynesian revolution in government, one in which Keynes himself participated, would have been all about full employment and fiscal stimulus. In fact, in the 1940s it was all about how best to achieve to inflation control.

In the UK, the 1941 budget, marked the first attempt to estimate and manage aggregate demand in order to reduce inflationary pressure. In 1947 the UK Labour government used Keynesian analysis to justify its austerity budget to control inflation. The Economic Section headed by the Keynesian James Meade, argued that price subsidies should be cut. In the short-run that might result in price increases but by reducing macroeconomic imbalance it would help to reduce inflationary pressure in the medium-term.

So strong was the emphasis on inflation-control that if you take the true message of Keynesianism to be the argument for budget deficits to stimulate aggregate demand for the sake of ensuring full employment, you might ask in the British case, whether the Keynesian revolution ever happened. That was Jim Tomlinson’s skeptical view.

In climate terms, how would we feel, if we were using energy and CO2 models to gauge the impact of investing in a large fleet of coal-fired power stations? That is the situation of climate activists when it comes to India or China, not the US or the EU.

Of course, you could take the view that Build Back Better is billed as a climate measure, so it is unsurprising that it is scored in climate terms. We will have to see whether the CO2 approach will generalize to other policy domains, assuming, of course, that the Biden administration gets to pass any further legislation.

It will be interesting to see, also, whether the kind of CO2 analysis of fiscal policy put into action in the US begins to operate in Europe as well.

It is an interesting test of how far the climate governance framework is truly becoming hegemonic. Will CO2 metrics become as omnipresent as GDP currently is?

In the mean time, the general point stands. When we are looking for innovation in economic policy, hard-fought rearguard actions should be as interesting as the moments when history appears to lurch forward.

After all, when do you have to think most carefully about how to get what you want? When you have a big blank canvas and and unlimited budget? Or when you are trying to dance in a phone booth?

***

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.