A sketch map.

In the recovery from the COVID shock of 2020 there is a stark gap between the rapid rebound of rich countries and the slower recovery of middle-income and low-income economies. It is important to recognize this stark difference and how 2020 differs in this respect from the 2008 crisis. But dividing the world in this dualistic way, between rich and poor, sacrifices any geographical detail. We lose sight of the way the problems afflicting economies and societies in a region can compound each other.

I wrote in Chartbook 20 about the Caribbean and Central America. In commentary of late, South America has been singled out as a possible zone of interlocking crises.“Three shocks unsettle business confidence across Latin America”, warned a recent FT headline.

Regions of polycrisis might be defined succinctly as zones in which the collective trouble is worse than the sum of its parts. Think of a region where climate change brings drought or a historic hurricane that crosses borders, creating misery and refugee flows, with no safe place to go. Think of regions wracked by geopolitical tensions and local rivalries.

Alongside Latin America, another region that might be thought of in these terms, is the region that Fred Halliday once dubbed Western Asia, a region that stretches by way of Pakistan and Afghanistan, to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Turkey (figures refer to population estimates).

The aggregation population of these countries is 491 million, comparable to that of the EU (445 m) or Canada-USA-Mexico (497 m).

State borders in this region are some of the most arbitrary in the world. The Kurdish population of 40 million stretches across Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Millions of displaced people from Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq lived in improvised camps. The economies are interconnected through the use of multiple currencies, trade and infrastructure connections, particularly for energy. Climate change has inflicted simultaneous drought on Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. Altogether, the region presents a landscape of crisis more intense than anywhere else in the world.

At the Eastern end of the region, following the Western withdrawal and the Taliban takeover, Afghanistan is on the edge of catastrophe. The UNDP and the IMF are predicting that the Afghan economy may contract by 20-30 percent in a single year, an unprecedented collapse. “Nine out of 10 Afghans are expected to fall below the poverty line by next year. More than half of the 39m population require food assistance.” The G20 meeting in October agreed to take action to address the humanitarian crisis. But despite UN appeals, the foreign assets of Afghanistan to the tune of $9.6 billion remain frozen.

Today is international #GISDay. #GIS plays a critical role in all that we do.

— The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (@theIPCinfo) November 17, 2021

Behind this map of #Afghanistan, there is the work of 51 analysts, 45 analysis areas, and the #foodinsecurity status of over 41 million people. #GIS helps us get information to those who can help. pic.twitter.com/d2HAEQmYVu

All eyes were on Afghanistan at the moment of Western withdrawal, we should not avert them now that tens of millions of people have to suffer the consequences.

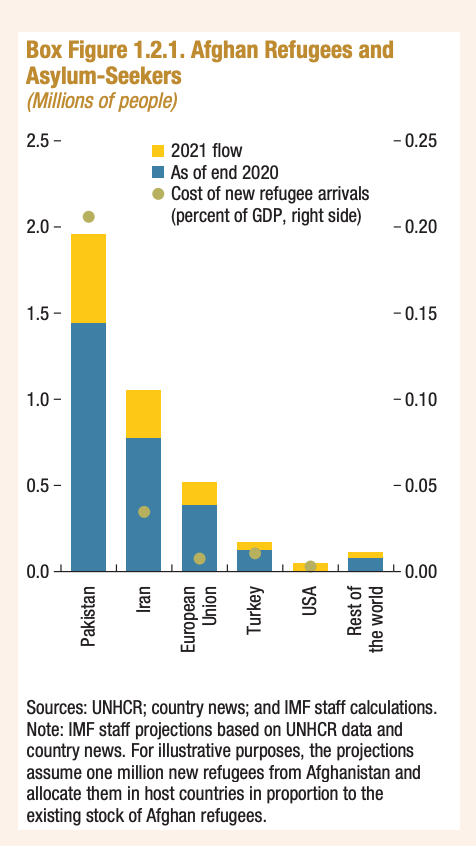

Afghanistan’s immediate neighbors will have no option. Refugees are already beginning to flood into Pakistan and Iran. These are the latest IMF estimates.

Source: IMF

Pakistan is in no position to provide much support to the Taliban regime or to Afghan refugees. As the FT recently said:

“Pakistan’s more than 220m people were spared the worst of the coronavirus pandemic’s initial economic shock, thanks in part to the government’s policy of shorter, looser lockdowns. But they are now facing a new crisis: inflation has surged to the worst level in years, with an index tracking everyday essentials such as fuel, food and soap last week rising above 18 per cent year on year. The rupee has also tumbled to all-time lows, losing 15 per cent of its value against the dollar in six months. Officials fear a surging import bill will deplete foreign currency reserves and further destabilise the economy.”

This poses a major challenge to PM Imran Khan. He came to power in 2018 promising to end “the country’s cycles of economic instability, where high debt and low foreign currency reserves forced repeated bailouts from institutions such as the IMF. But Khan has found himself trapped in this same vicious rhythm ….”.

Since December 2017 the Pakistani rupee has devalued by half. Under Khan’s premiership the devaluation has been 30 percent.

The Taliban victory was celebrated as a victory also for Pakistan, but without strong US backing it is unclear whether Pakistan has the platform to really take advantage. China is Pakistan’s main strategic ally, but on that front too there are mounting difficulties. BRI programs, once loudly hailed, are making disappointing progress.

Apart from Pakistan, Iran is the immediate destination for most people fleeing Afghanistan. In the last few weeks it is reported that some 5,000 Afghans are entering Iran every day. Iran has the resources to cope, but it too will suffer as a result of the Afghan implosion. Since 2018 when Iran faced a dramatic intensification of US sanctions, Afghanistan has served Iran as a conduit for $5billion per annum in cash. Both the US and Iranian currencies were in widespread use in Afghanistan. “… the Iranian rial has been broadly used in western border provinces, such as Herat, Farah and Nimroz. … the Herat governor tried to ban the use of the rial in 2019, arguing that Iranian currency was entering the Afghan economy to essentially drain US dollars. However, usage of the rial has broader driving factors too. There has been extensive drug smuggling originating from Afghanistan, boosting financial exchanges between the two neighbors. Moreover, numerous Afghan border communities purchase many of their supplies inside Iran, hence the demand for the rial.” Now the Taliban have issue a ban on foreign currencies. That may help to explain why the Iranian currency, the rial, weakened as the Taliban consolidated their grip.

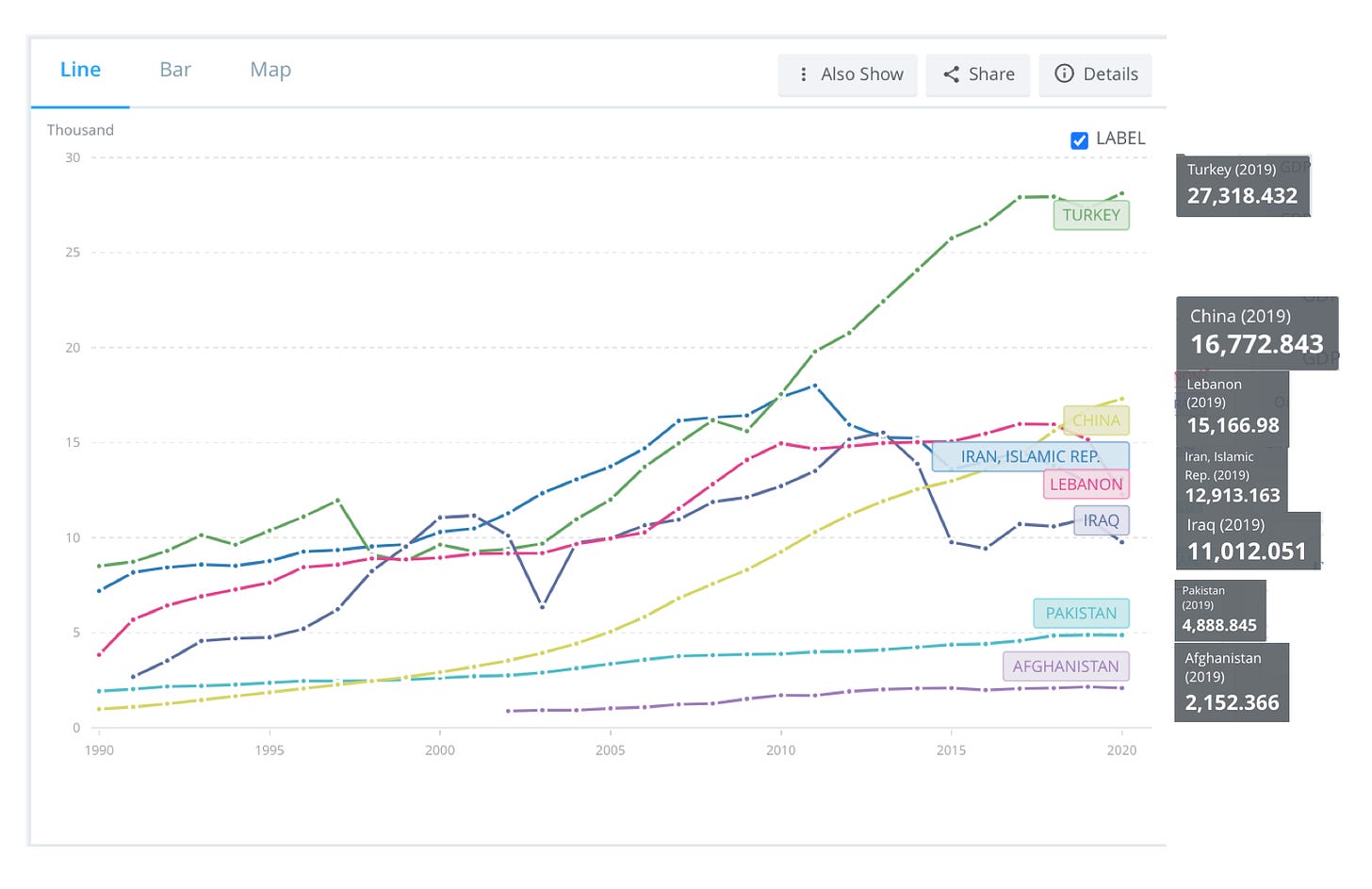

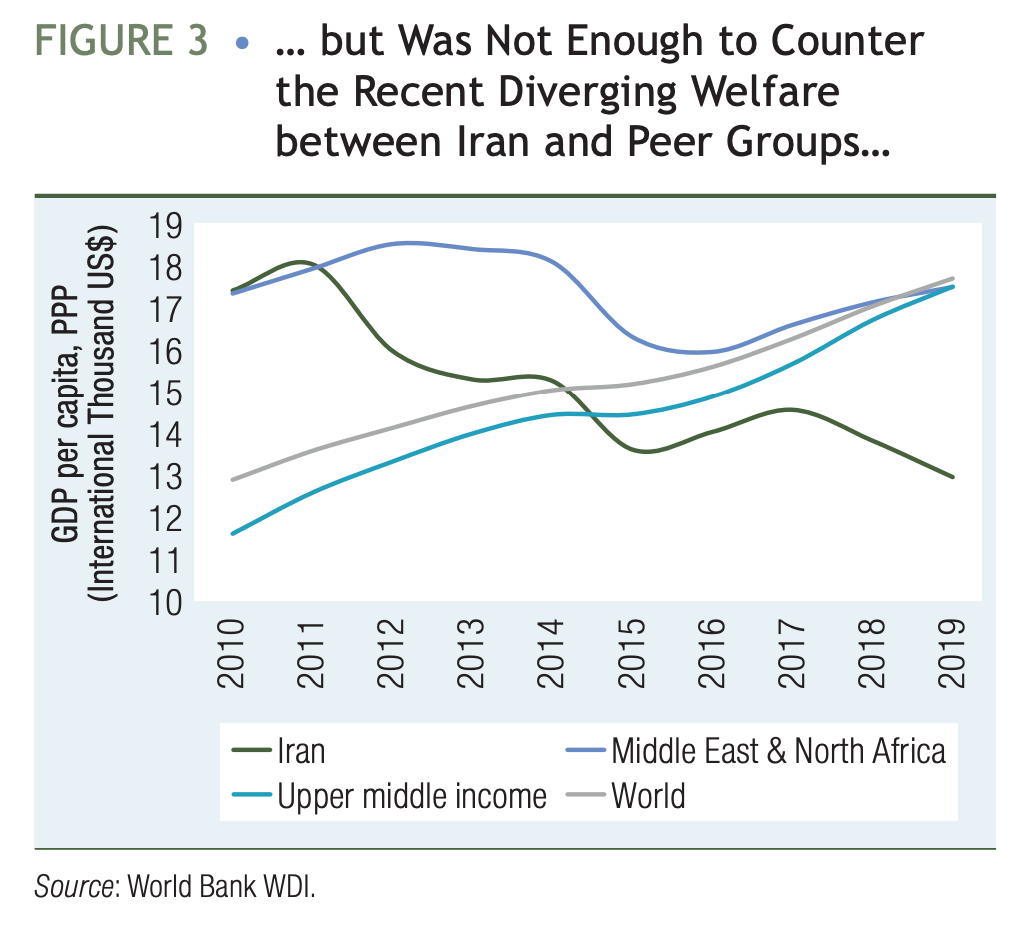

Severe as the spillover from Afghanistan to Iran may be, one should not imagine that they are in the same boat. Whereas Pakistan and Afghanistan are stuck at low levels of income. Iran is a middle-income country with a large and highly diversified economy. It is far less agrarian than Pakistan and far less dependent on oil than Iraq. A chart of PPP-adjusted GDP per capita divides Western Asia into three regions.

Given its sophistication and population of 80 million, Iran has the potential to be an economy on the scale of Turkey or Saudi Arabia, both of which are members of the G20. That it is not, is a matter of politics, geopolitics and political economy – the state-run political economy of the Islamic Republic and the dramatic pressure of sanctions. If you bring Iran’s economic development over the last decade into close up, the impact of sanctions is clear. In the summer of 2010, the Obama administration and the EU moved towards an aggressive tightening of sanctions. Within a year you can see the impact in Iran’s GDP per capita figures. The nuclear deal of 2015 brought some relief, but with the maximum pressure policy of the Trump administration from 2018 onwards the decline resumed.

Cameron and I discussed Iran’s situation on Ones and Tooze. In that discussion I made a mistake. I claimed that Iran’s population growth was rapid. It is not. It is weird. Population growth surged in the 1980s, producing a youth bulge, but it is now as low as 1 percent per annum. That bulge accounts for the chronic problem of unemployment.

The latest round of sanctions initiated by Trump have delivered a severe blow. Over the winter of 2017 the news of Trump’s new stance, combined with domestic resentment over price increases to trigger something like a comprehensive crisis of the regime. There was a shock devaluation and inflation surged. Today, at 40 percent, inflation remains the most acute economic problem facing Teheran.

As a backgrounder on the current Iranian economic situation I found this videoed conference interesting. As the speakers in this session make clear, the impact of sanctions is severe, but Iran does not face immediate collapse. Oil is an important part of the Iranian economy, it drives exports and investment and tax revenue. But even when oil prices are high, it accounts for not more than 10% of GDP. Furthermore, under the pressure of sanctions Iran has moved up the value chain. It can now export not just crude but petroleum and diesel, which gives it considerable leverage with its cash-strapped neighbors.

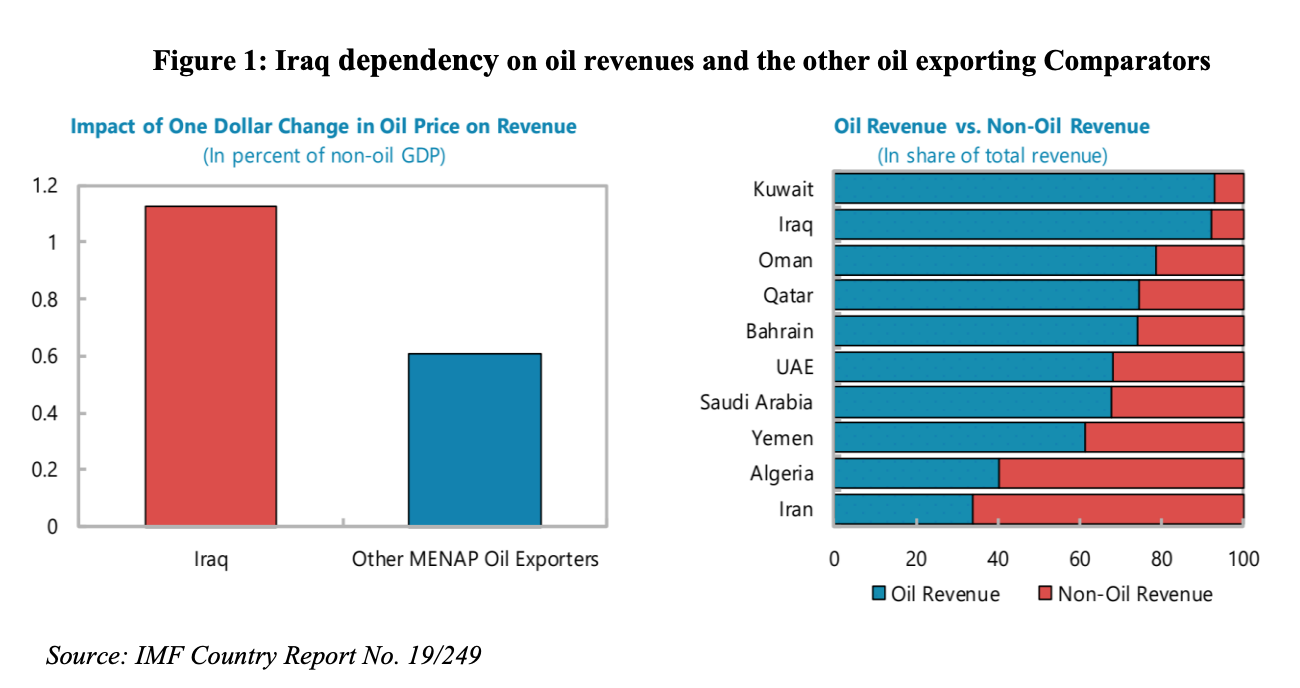

Iran, in short, is not Iraq, which is a caricature petrostate with a vastly overgrown public sector that serves as the fiefdom of rival factions, many of which also command powerful armed militias. The combination of COVID and the collapse in global oil prices triggered a moment of existential crisis in Iraq in 2020. The failed development of the last decade was cruelly exposed. The upshot was an apocalyptic assessment by a team of experts delivered in October 2020 in the form of a White paper report.

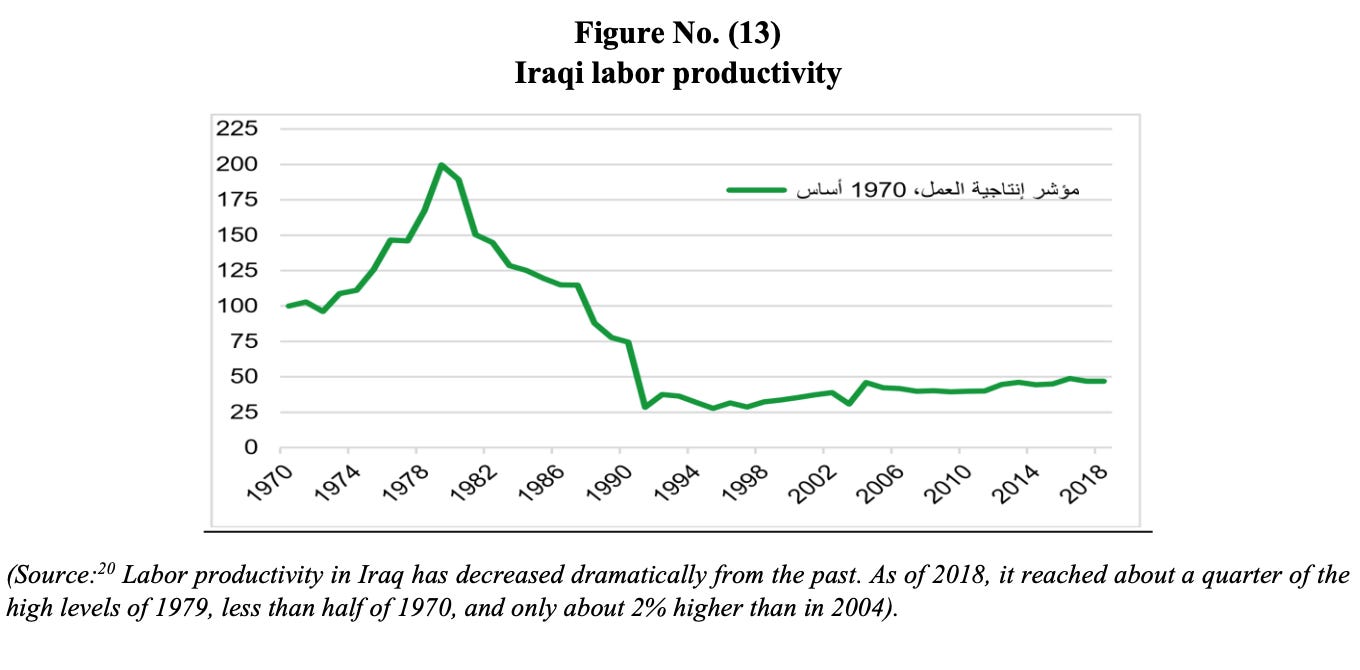

Non-oil tax revenues in Iraq amount to a laughable 1.4% of GDP, compared, for instance, to 27.8 or 30.%% in Angola or Algeria. Other than oil, Iraq has no exports to speak of. Crude oil exports account for 95 % of Iraq’s exports, compared to c. 60% for Saudi Arabia and Iran. Iraq’s labour productivity record over the last half century is one of the more shocking graphs you are ever likely to see.

A panel on Iraq’s economic situation posted to youtube in January 2021 by Chatham House delivered a remarkable sense of urgency. It is also, however, a historic document. The reform demands of the White Paper were always exorbitant and since then the immediate pressure has been lifted by the resurgence of oil revenues. The upshot of a more recent LSE panel chaired by the excellent Chloe Cornish of the FT in September 2021, was that so long as the oil revenues continue to flow, so will Iraq’s lopsided political economy limp along.

Iraq remains a disaster waiting to happen. Where this has registered most recently on Western radars is in the appalling scenes on the Belarus and Poland border. Of the 16-17000 people stuck between the two East European countries, between 7,500 to 8,000 are from the Kurdistan region of Iraq, thousands of miles to the South.

The Kurdish region of Northern Iraq (KRI) under its own government (KRG) was once a safe haven. Of its 6 million inhabitants one million are refugees mainly from other parts of Iraq but also Syria. But in recent years the KRG has faced deteriorating economic conditions forcing salary cuts for its one million civil servants and austerity. This in turn is a spillover from the national financial crisis in Baghdad, brought on in 2014 by the collapse of oil prices. This produced a 90% drop in financial transfers from the central government to the KRG. The simultaneous upsurge of ISIS and the collapse of oil prices in 2014 was a perfect storm. Added to which, KRI politics is dominated by brutal and increasingly repressive infighting between two parties: the Barzani family-led Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Talabani family-led Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Meanwhile, the SIS threat remains acute, particularly in the “disputed areas” between Erbil and Baghdad, …. According to a KRI spokesperson, most of the Kurdish migrants fleeing to Belarus hail from the “disputed areas” as well as Duhok Governorate, where conflict between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) continues.” Recent Turkish offensives against the PKK in the region have caused damage in over 800 villages in the KRI.“

The struggles across the Kurdish region of Iraq are one example of the pattern that repeats in Syria and Lebanon. Powerful external players – notably Iran and Turkey – maneuver violently for influence in zones of failed or fragile states.

Lebanon was once a safe haven in the region, but since 2018 it has been dragged down by disaster. It is hard to overstate the scale of this collapse. In the spring of 2021 the World Bank reported that: “The Lebanon financial and economic crisis is likely to rank in the top 10, possibly top three, most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century … Lebanon’s GDP plummeted from close to US$ 55 billion in 2018 to an estimated US$ 33 billion in 2020, with US$ GDP/ capita falling by around 40 percent. Such a brutal and rapid contraction is usually associated with conflicts or wars.”

Financial incontinence on an epic scale, corruption, factional infighting, macroeconomic imbalances suspended in mid air, Lebanon’s economy, borders on the surreal. But the effects on the ground are devastating. A society once fabled for its wealth and cosmopolitan culture has been reduced to hunger and acute shortages of essentials. And the situation is getting worse by the week.

In November, the near total collapse of the electricity supply have forced the US and the World Bank to stitch together an emergency program to supply Lebanon, once the financial and cultural powerhouse of the region, with gas from Egypt and electricity from Jordan.

The embarrassment for Washington is that to build a rescue platform for Lebanon it is hard to avoid going through Syria, itself in ruins following a decade of brutal armed struggle. Since 2018 the fighting in Syria has calmed, but the economic situation is disastrous. It reached a peak of intensity in 2020 when the announcement of a new wave of Congressionally-backed sanctions – “the summer of Ceasar” – triggered a panicked devaluation of the Syrian currency. The impact of the new wave of sanctions is unclear, but the collapse of the currency, on top of the COVID shock dramatically increased the pressure on the Syrian population. It was, as one particularly compelling report put it, a perfect storm.

As the Assad regime tightens its grip, the battle for influence continues. Iran spent between $20 and $30 billion backing his regime during the decade of armed conflict and would like to see a return on its investment. But Iran is hobbled by sanctions and lacks the cash to compete with Assad’s new friends in the Gulf. As Amwaj comments: “UAE’s entry as a regional economic giant into the Syrian market will push Iran further to the sideline, considering actions like Abu Dhabi’s promise to build a solar plant near Damascus”.

In Syria, the last remaining resistance stronghold is the starving and freezing enclave in Idlib, home to about 4.4 million people, about half of them refugees. About 75 percent of Idlib province residents are in need of humanitarian assistance. Their one land-connection to the outside world is the Bab al-Hawa border crossing to Turkey, effectively controlled by the Islamist HTS.”

In 2019 as the Lebanese economic crisis escalated, the Syrian pound began to collapse, destablizing Idlib’s precarious economy. In the summer 2020, in search of a financial lifebelt, the Islamists introduced the Turkish lira as the new currency throughout Idlib province. They did so just in time to avoid the precipitate collapse of the Syrian currency following the US sanctions announcement. As a result, prices in Idlib province did stabilize for eighteen months, only for disaster to strike again, this time from across the border to the North.

In 2021 Erdogan, Turkey’s capricious President embarked on his latest confrontation with the financial markets and Idlib’s Turkish currency anchor was torn loose. When the Turkish lira was introduced as a means of payment in Idlib in 2020, the exchange rate was 6.8 lira for one US dollar. As of December 1 2021 it had crashed to 12.9 lira. The result was a savage spike in living costs as the price of imported fuel surged.

Turkey’s rollercoaster financial ride through 2021 is the clincher in the crisis narrative of Western Asia. Turkey is a major geopolitical player (in Libya, Syria, Iraq, Azerbaijan-Georgia). It is a contender in Eastern mediterranean energy politics. It is the key to one of Europe’s refugee crises. It is a major regional power. Its destabilization would have huge regional implications.

But amidst all the crisis talk we also have to put Turkey’s situation in perspective. Since its last major financial crisis in 2001, Turkey’s per capita income, in PPP adjusted terms, has tripled. That remarkable growth is the foundation for Erdogan’s legitimacy. It is also that track record that has given Turkey’s its financial staying power. Seemingly, no matter what Erdogan does, the investors ultimately come back. Since 2018 Erdogan has been flirting with disaster. The question for the months ahead is whether this time Erdogan has gone too far. Inflation in Turkey is accelerating. There has been a huge shock to imports that will generate a current account surplus but also inflict pain on the population. Can Erdogan survive once again?

***

I am acutely aware that a survey like this cannot really do justice to the complexity and drama of the terrain it surveys. The drama and complexity of this region is mind-blowing. In the mean time, a scrapbook may be helpful in orientating ourselves in the flow of daily events. It provides a framework for thinking about the interconnectedness that defines major world regions. It may help to focus our attention on the extraordinarily acute crises facing the populations of Afghanistan and Lebanon, the responsibility of the United States and its sanctions policies in Syria and Iran, and the responsibility more generally of richer and more capable states to act where necessary to relieve humanitarian disaster.