Making sense of Manchin

The New York Times headline on Saturday morning screamed:

Key to Biden’s Climate Agenda Likely to Be Cut Because of Manchin Opposition

The West Virginia Democrat told the White House he is firmly against a clean electricity program that is the muscle behind the president’s plan to battle climate change.

This is the nightmare many advocates of a progressive US climate policy have long been haunted by.

The clean electricity program that Senator Joe Manchin (WV) has turned against is the cornerstone of the Biden climate program. Driving first coal and then gas out of the US electricity system, combined with a big push on EV, were the twin mechanisms through which the administration hoped to meet its objective of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions by 50-52 relative to 2005 levels by 2030. It was always feared that Manchin might dig in on gas. It now seems that his position has hardened to one of outright opposition to any form of clean energy provision in the spending package. Without the clean electricity program it is hard to see how the United States can make good on its climate promises. Unless Manchin flips, America will go to the global climate talks at COP26 at Glasgow with nothing to offer.

Manchin is the senior senator for West Virginia, commonly described as “coal country”. He is a Democrat in a massively Trump-voting state. As the NYT reported, West Virginia’s other senator, the Republican Shelley Moore Capito, “said she was “vehemently opposed” to the clean electricity program because it is “designed to ultimately eliminate coal and natural gas from our electricity mix, and would be absolutely devastating for my state.””

The power that West Virginia’s two Senators wield is astonishing considering that the state has a total population of 1.79 million – as compared, for instance, with the New York borough of Brooklyn which numbers 2.89 million inhabitants. West Virginia’s swing votes in the Senate are another demonstration of the warped constitution that the 21st-century United States has inherited from the eighteenth century.

By way of their influence in Washington, West Virginian politicians have repeatedly stymied not just American, but global climate policy. As Lee Harris reminds us in a timely piece in American Prospect, in 1997 it was West Virginian Democrat Robert Byrd who, along with Chuck Hagel, blocked American ratification of the Kyoto climate protocol negotiated by the Clinton administration.

West Virginia’s identity is deeply tied up with coal. So too is Joe Manchin’s personal fortune. See this Guardian investigation and this hard-hitting piece in The Intercept.

But, how deep is the state’s economic dependence on fossil fuel extraction? Is Capito right? Would decarbonization be devastating for West Virginia?

Back in September Paul Krugman announced in the Times: “Dear Joe Manchin: Coal Isn’t Your State’s Future”

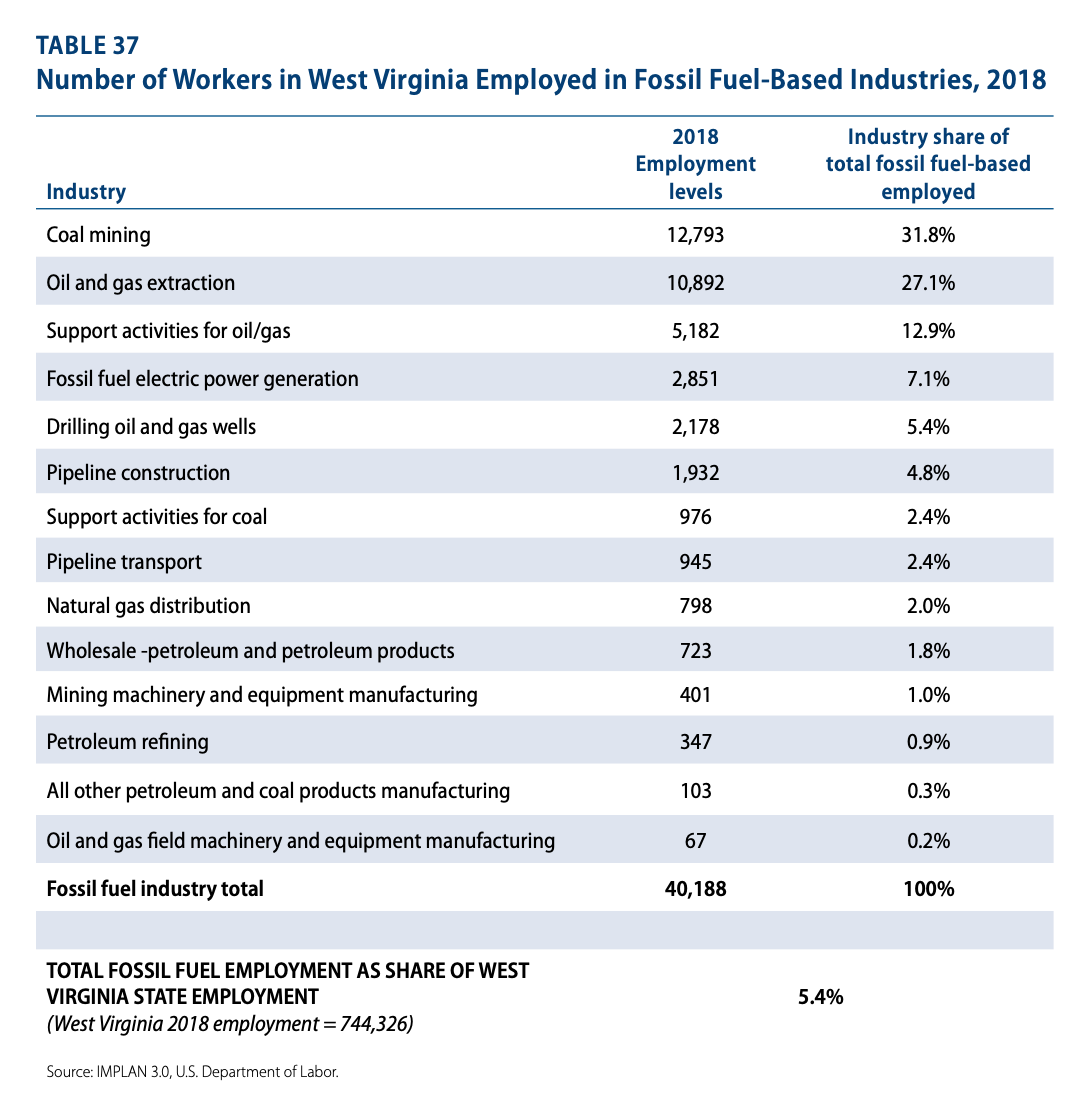

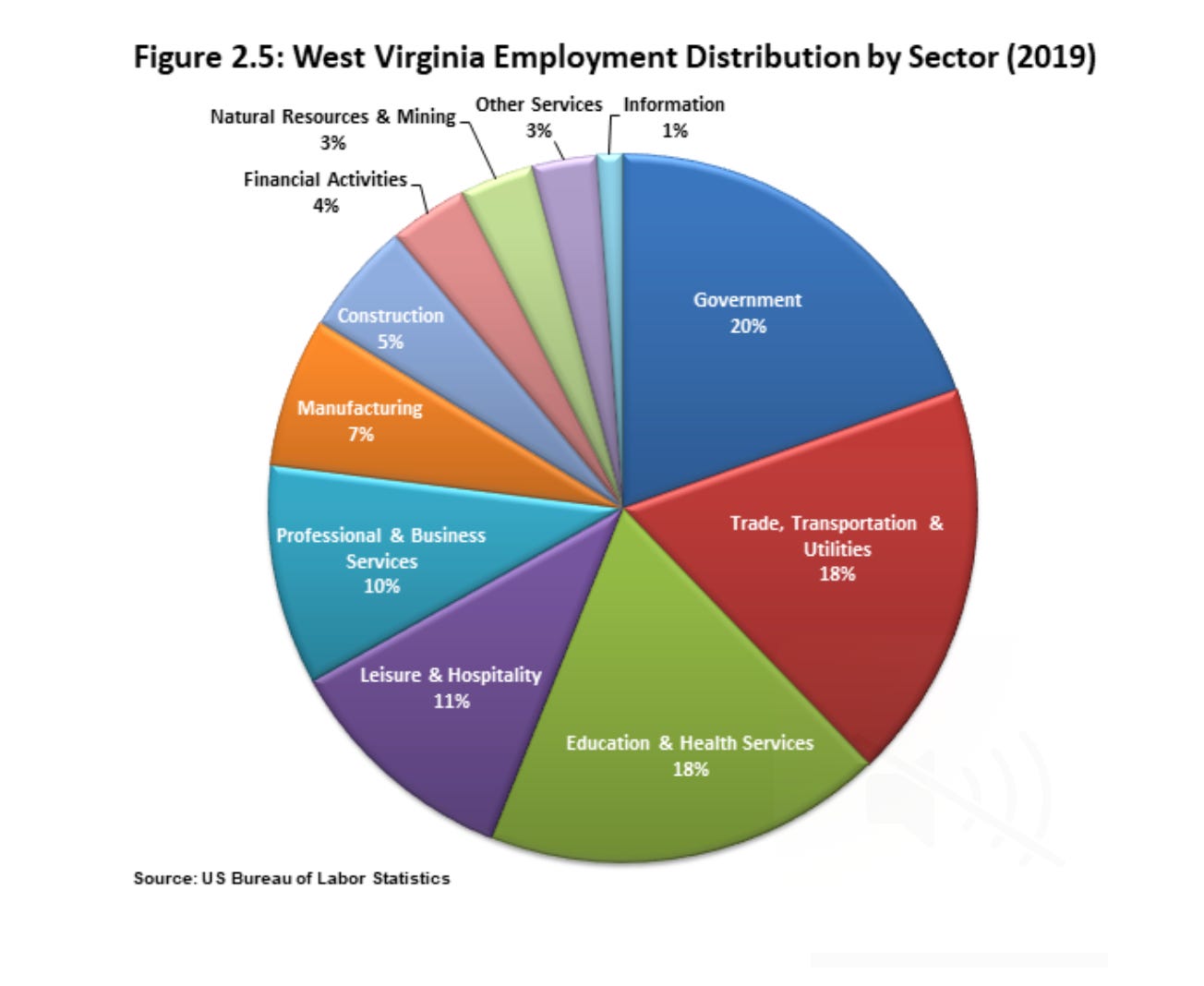

“It’s actually startling how small a role coal plays in modern West Virginia’s economy. Before the pandemic, the coal mining industry employed only around 13,000 workers, less than 2 percent of the state’s work force. Even attempts to make the number look bigger by counting jobs indirectly supported by coal suggest a state that has overwhelmingly moved on from mining. So what does the state do for a living? These days West Virginia’s biggest industry is health care, which employs more than 100,000 people (and offers many middle-class jobs).”

As Krugman points out, what has run down coal in West Virginia are not liberal environmental regulations, but market forces. Meanwhile, health care as a growth industry shows the benign face of big government at work.

“Federally subsidized health care is particularly important in West Virginia, where Medicare beneficiaries are a quarter of the population, compared with only 18 percent of the nation as a whole; the state also experienced a very rapid decline in the number of uninsured after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act.”

It is easy to agree with Krugman that coal is not West Virginia’s future. But, if the matter were as simple as Krugman presents it as being, it would be truly puzzling that West Virginian politicians are as dogged in their defense of the status quo as they are.

Is the energy interest really as trivial as Krugman suggests? In trying to answer this question one descends into a bewildering mesh of politics, theory and empirics. This is itself significant. The fossil fuel lobby in West Virginia is well-defended in ideological terms. It is not a matter simply of denial. It continues to offer an entire vision of the local economy, which is inextricably tied up with fossil fuels.

The West Virginia news site that Krugman cited in support of his contention that coal was irrelevant, was actually making the opposite case. It was quoting a report commissioned by the West Virginia Coal Association from West Virginia University’s Bureau for Business and Economic Research (BBER).

I would love to learn more about the history of the BBER. The website says that it traces its history back to the 1940s. Does anyone know more? How did this regional hub of expertise get established in coal country?

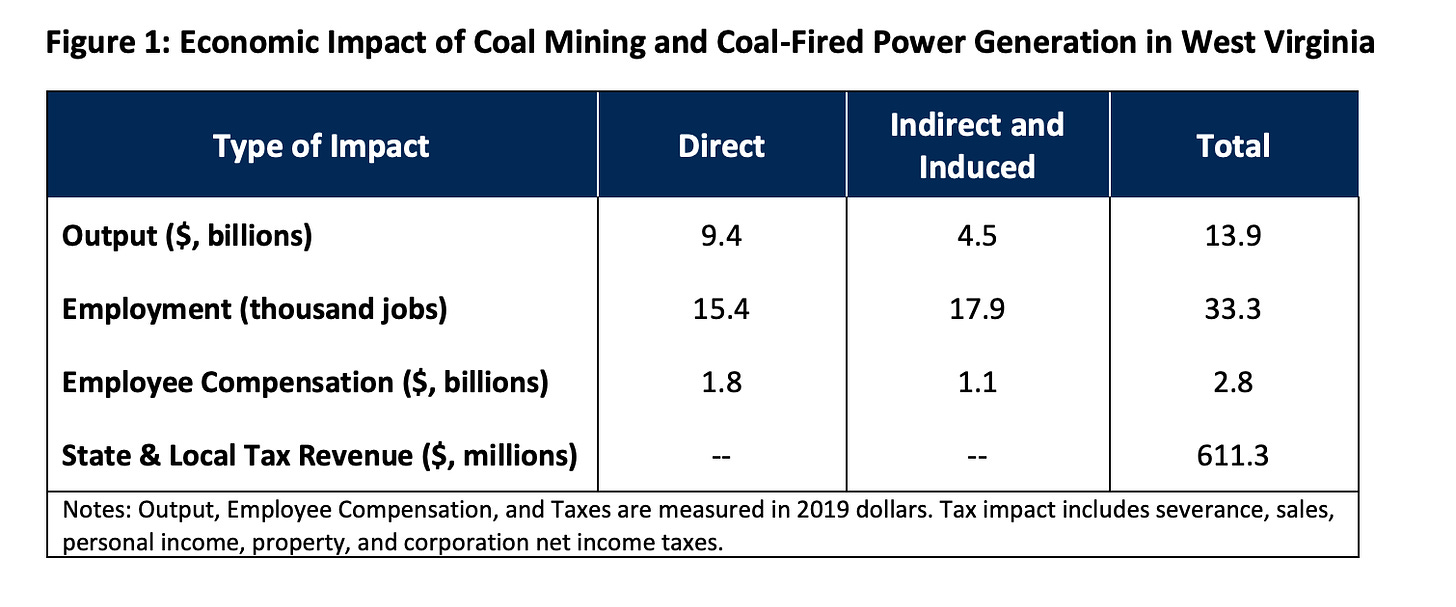

The BBER’s latest report on the coal industry’s significance for West Virginia claims “that the mining industry alone spends more than $2.1 billion on wages and coal operators generated approximately $9.1 billion in economic activity in 2019, far more than the entire general revenue budget of state government.” All told, the “combined economic impact of coal mining and coal-fired electric power generation was approximately $13.9 billion, meaning the industries supported 17 percent of the state’s total economic output or one out of every six dollars generated.”

The BBER’s commissioned report can be accessed here. The key table is the one below:

The definition of output used in this table is somewhat unclear. As Krugman suggests, the “multiplier” methodology, in which an industry is credited with supporting thousands of other jobs through its purchases of inputs from other sectors, can easily be used to generated inflated numbers. The more conservative route would simply be to compare value added in coal-mining and ancillary services with state-level GDP of $78.86 billion. Alternatively one could weigh employment and the wage bill.

But even the simple question of how many workers are employed in coal-mining and related services is not uncontentious. Krugman cites a figure of only 13,000. From the following compilation put together by PERI UMass it is apparent that this does not include contractor or ancillary workers.

Source: PERI UMASS

The coal experts at the BBER count a total of 33,000 workers in coal mining and coal-fired power generation. Hard-core advocates of the coal industry go further. They cite data from the West Virginia Office of Miners Health, Safety and Training (WVOMHST) which “reports 15,440 direct coal mining jobs and 37,463 contractors, for a total of 52,903 coal industry jobs in the state”.

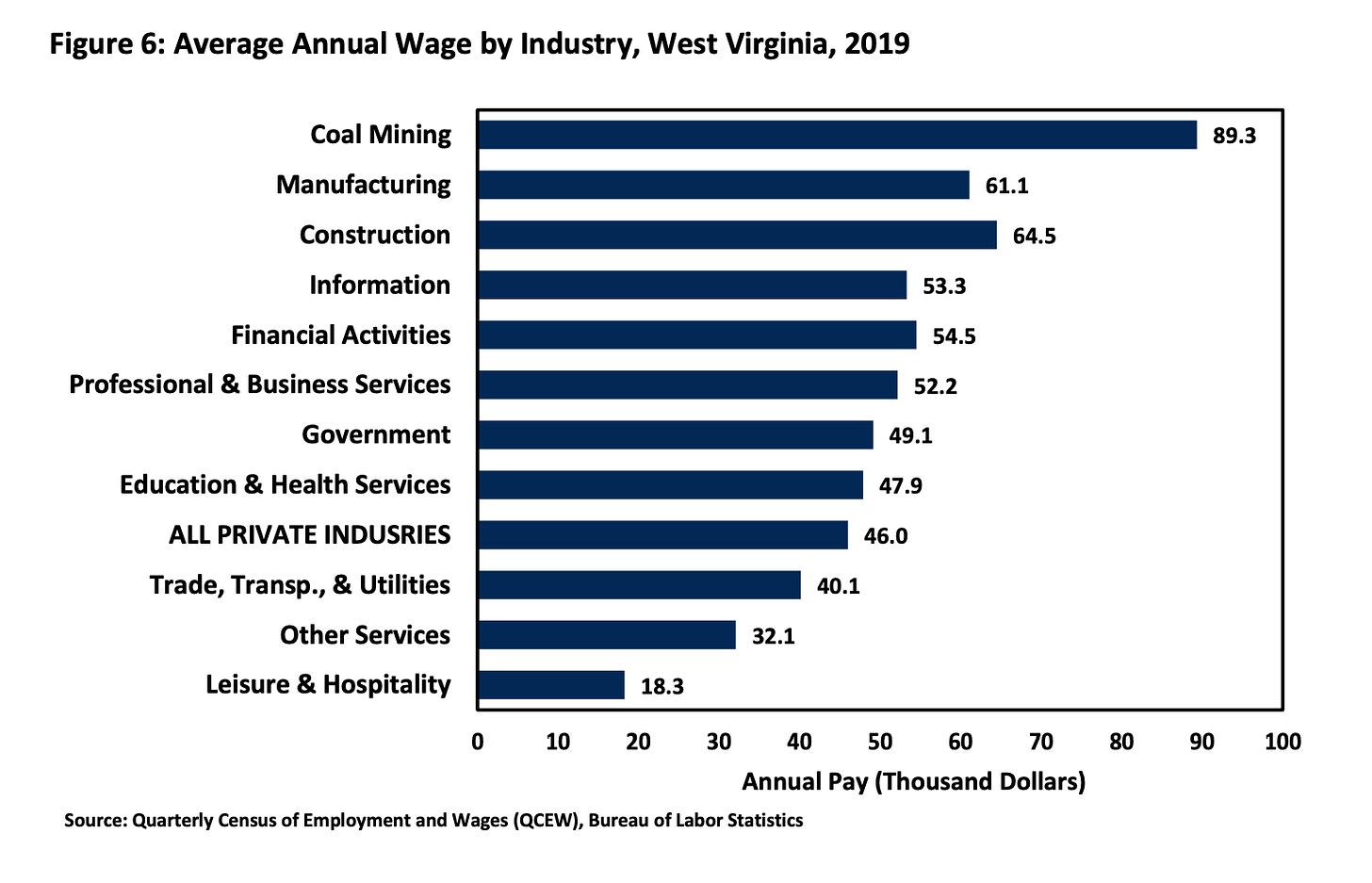

Relative to West Virginia’s pre-COVID non-farm employment of 720,000 that would imply a share of employment somewhere between 2 and 7.3 percent. That is a long way form the 17% share of output claimed by the BBER. Admittedly, the significance of the coal workforce is multiplied by the fact that they earn significantly higher wages. Again the figures vary. According to the BBER report, annual average wages in West Virginia ranged as follows.

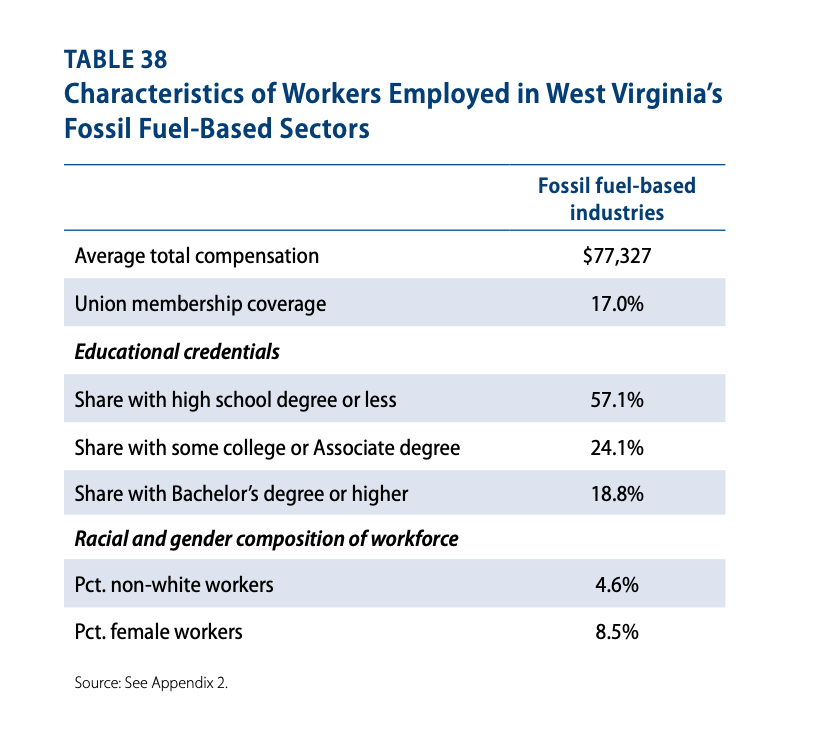

Applying these pay differentials to the range of employment figures would imply a coal share in the wage bill of between 4 and 14.3 percent. But once again one must ask, are these extremely high numbers of coal-industry wages really plausible? The UMass report on the West Virginia fossil fuel sector gives a figure for earnings of $77k.

Four things, at least, are clear. The coal sector has declined and will likely continue to decline, despite occasional upswings as in 2018-9, whether Joe Manchin wins his rearguard action or not. Secondly, the battle over coal is over more than 2 percent of the West Virginia economy. The high-side estimates would come close to one in six jobs in the state. Thirdly, it is not just coal that is at issue. Gas is no less crucial. According to the UMass study, more than half the fossil-fuel sector jobs at stake are in gas and oil. Estimates by the BBER suggest that gas adds almost as much to West Virginian gross state product as does coal. According to its somewhat opaque methodology, nearly one-third of state GDP in 2019 can be attributed to fossil fuels. This is the kind of vision of West Virginia’s economy that makes decarbonization a mortal threat.

The other thing that is clear is that though the health care sector that Krugman champions is large. It promise for the future of West Virginia is ambiguous. For one thing, it pays significantly less than the energy sector jobs that are at risk. I worry that lumping education with health care workers may be a ploy on the part of the BEER. In any case, wages in that sector are barely half those in coal.

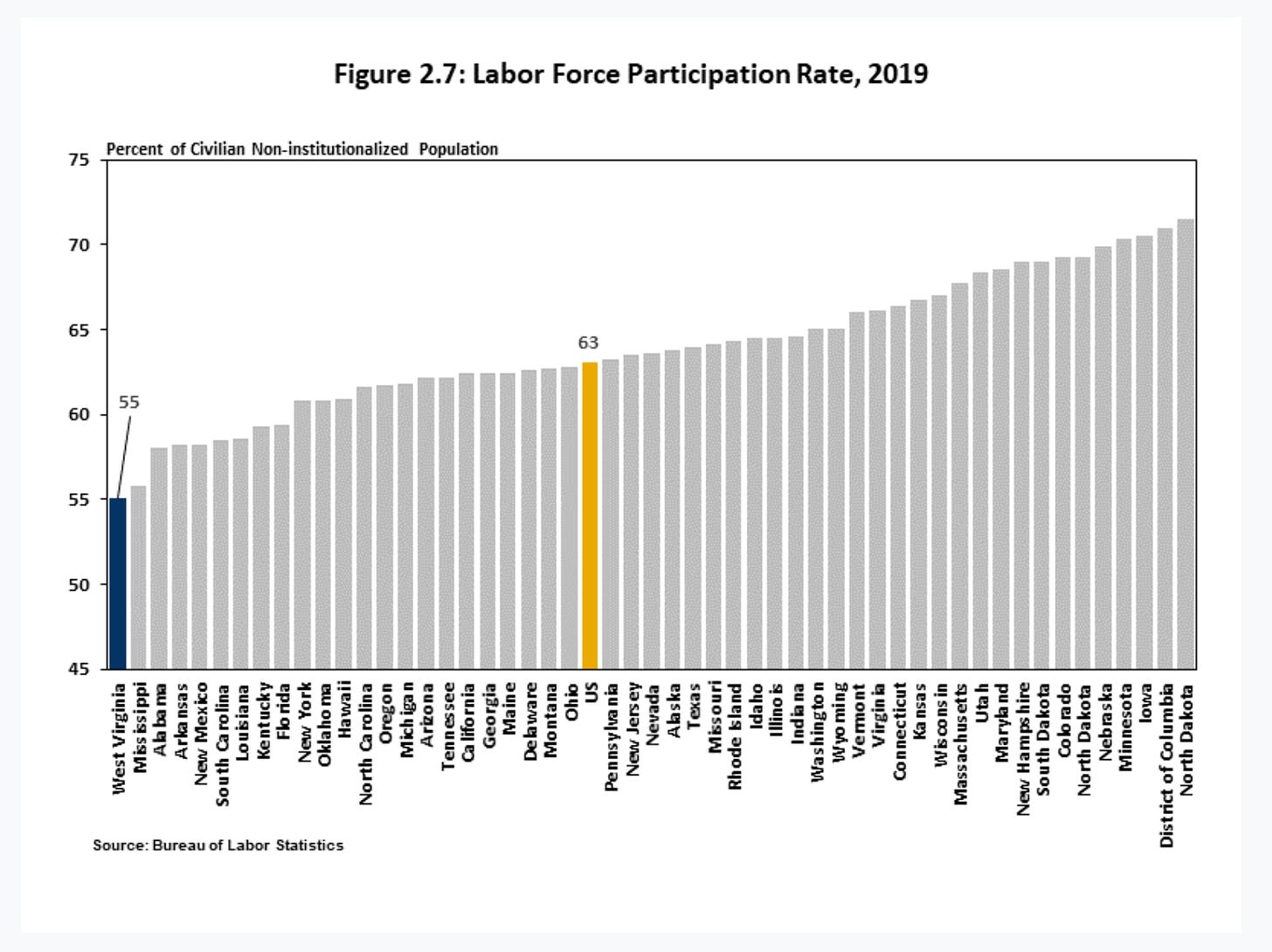

Krugman is right that health care is a larger and more dynamic employer. But one has to ask why. In the analysis of the BBER economists, the growth of the health care sector is less a bright promise of the future than a symptom of West Virginia’s economic and social distress. The large medical sector is servicing a population that is not just aging, but wracked by ill-health and an epidemic of “deaths of despair”.

As the BBER notes:

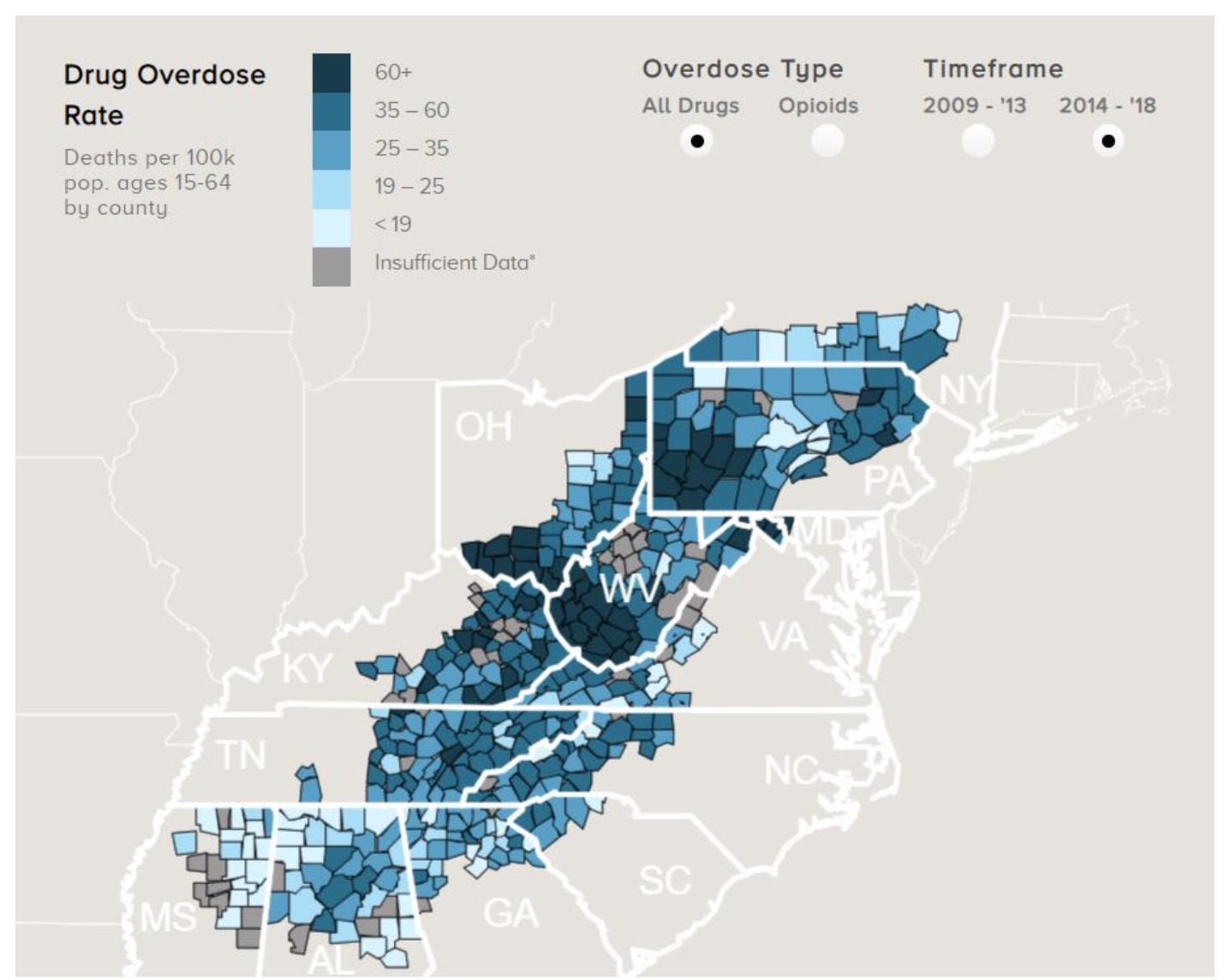

“According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), West Virginia’s age-adjusted mortality rate is the second highest among all states and also ranks among the tier of states with high incidences of heart disease, cancer and diabetes. Furthermore, behavioral or lifestyle factors that contribute to poor health outcomes such as physical activity during leisure time are among the lowest in the nation and rates of cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among the adult population are among the highest nationally. Another source of the state’s poor health outcome trends over the past decade or so has been the skyrocketing use and death from opioid overdoses. Indeed, crude mortality rates among young men – particularly those between the ages of 25 and 34 – have risen significantly. For example, even as the 25 to 34 population has shrunk by roughly 3 percent since 2012, deaths among residents in this age group has increased by nearly 17 percent ….”

West Virginia is at the heart of an epidemic that has swept Appalachia.

Source: ARC

It is not by accident that West Virginia has a labour force participation rate of 55%, the lowest in the United States.

No doubt this was not Paul Krugman’s intention, but against this backdrop it can seem almost cynical to advocate health care as the future for West Virginia’s economy.

It is good news, therefore, that a variety of coalitions have been at work trying to develop blueprints for an economic future for West Virginia that goes beyond tending to its own ailing population.

One plan has been developed by Robert Pollin at PERI UMass Amherst. It maps how an annual investment of $2-2.5 billion in renewable energy and land management sectors, would enable a gradual wind down of the West Virginia fossil fuel sector, whilst fully protecting the retirement rights of the existing workforce. The full program is here. Robert Kuttner interviewed Pollin about the plan for American Prospect.

But it is not just out of state experts who can see a different future for West Virginia. A grouping called the Appalachia Coalition has developed a blueprint for a sustainable future for the entire region from Southwestern Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Ohio and Kentucky.

Earlier in the year 100 members of Congress endorsed the so-called THRIVE resolution (Transform, Heal, and Renew by Investing in a Vibrant Economy). Under this version of the Democrat’s investment planning, West Virginia would get about four and a half billion per year, easily enough to fund a just transition in this small state.

Whereas the economists attached to the business school of West Virginia University repeatedly underscore the huge footprint of fossil fuels in the state, at the Law School the Center for Energy and Sustainable Development has worked out a glossy plan for decarbonization.

As David Roberts has outlined in an extremely helpful compilation on his Volts substack, Joe Manchin, in fact, has his own plan, the American Jobs in Energy Manufacturing Act. If he so chose, could be rolled into the larger Biden agenda, releasing tens of billions in federal spending that could be mobilized for West Virginia.

The polling evidence suggests that West Virginia voters are concerned principally not about coal, but about jobs and their long-term future. The Biden billions could secure that future, not by clinging to the old, but by investing in new jobs.

The claim that West Virginia’s economy depends on protecting coal and gas, is thus not a self-evident fact, but a strategic political and economic choice. It is a choice to double-down on a status quo which may be deeply entrenched but whose prospects are, by common consent, dwindling. It is a choice to reject the option of restructuring and new investment. Given the funds on offer, the reason that Manchin makes that choice is not so much economic, as tactical and political.

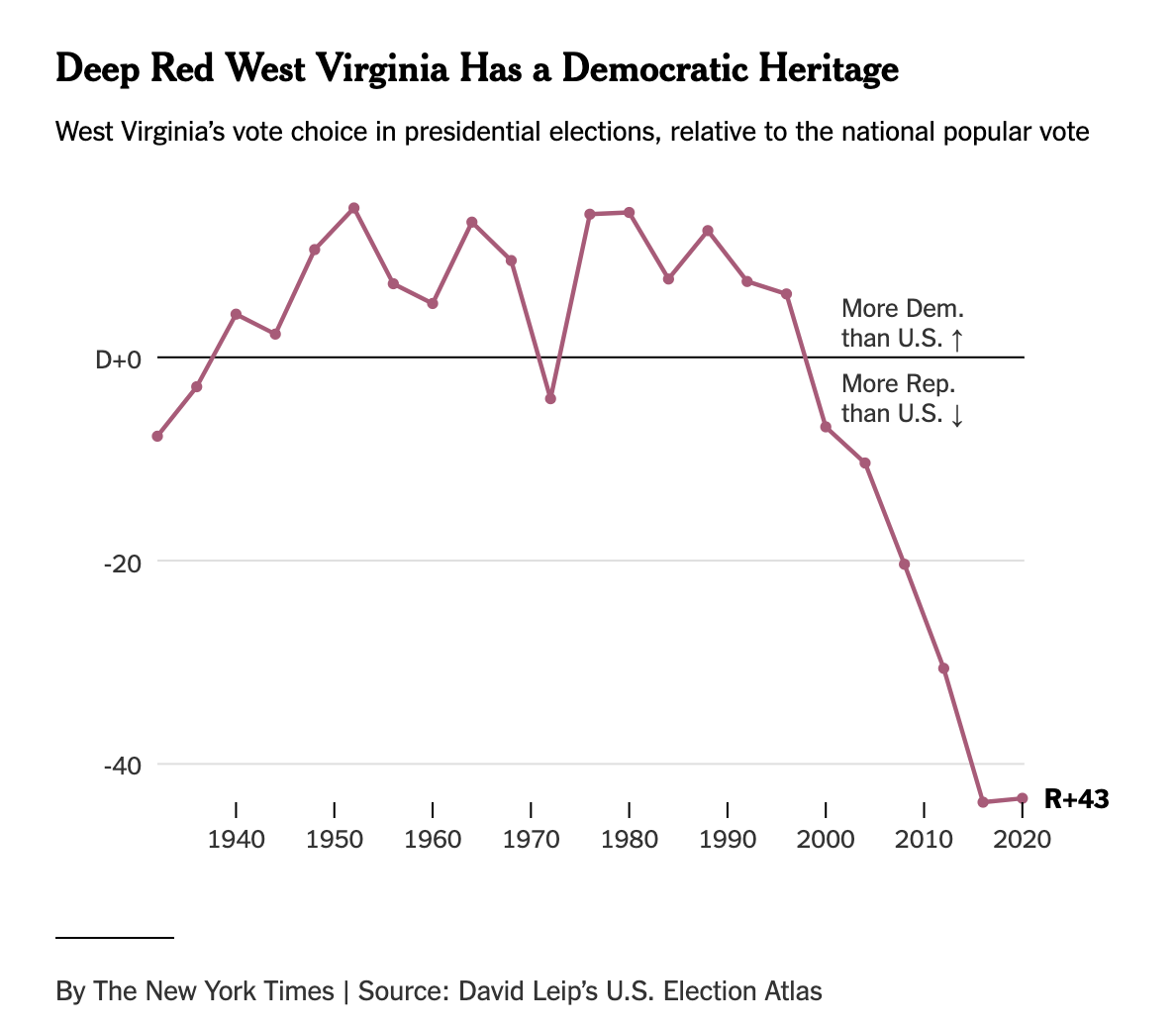

Manchin lives dangerously as a Democrat in a deeply red state, where to be tarred with the brush of woke liberalism is a political death sentence.

Manchin’s strategy of running as a Democrat but tacking away from the liberal agenda seems like a textbook demonstration of the kind of “popularist” tactics advocated by controversial political advisor David Shor.

For smart introductions to the popularist debate check out this by Eric Levitz and this excellent piece by Ezra Klein.

Shor argues that Democrats make a fatal mistake in taking on policy choices that appeal to liberal educated voters at the expense of working-class voters. As Klein reports:

Shor showed me, as an example, a set of environmental talking points he’d tested, in which the ones that mentioned climate change performed worst. “Very liberal white people care way more about climate change than anyone else,” he said. “So when you talk about climate change, you sound like a weird, very liberal white person. This is why policy issues matter more than people realize. It’s not that voters have these very specific policy preferences. It’s that the policies you choose to talk about paints a picture of what kind of person you are.”

True or not, this certainly is the lens through which much of the New York Times coverage frames the Manchin story. This, for instance, is how Nate Cohn describes Manchin’s political position:

Yet Mr. Manchin’s unique ability to survive in West Virginia is the last vestige of the state’s once-reliable New Deal Democratic tradition, dating to old industrial-era fights over workers’ wages, rights and safety. It was one of the most reliably Democratic states of the second half of the 20th century, voting in defeat for Adlai Stevenson in 1952, Hubert Humphrey, Jimmy Carter in 1980 and Michael Dukakis. The so-called Republican “Southern strategy” yielded no inroads there.

But Democrats began to lose their grip on the state during the 1990s, at least at the presidential level. In a way, West Virginia voters have been thwarting progressive hopes ever since. The promise of a new progressive, governing majority always rested on the assumption that the Democrats would retain enough support among white, working-class voters, especially in the places where New Deal labor liberalism ran the strongest. They did not.

By the late 1990s, the old New Deal labor Democrats no longer defined the party nationally. And when in conflict, the party’s growing left-liberal wing prevailed over working-class interests: New environmental regulations hurt West Virginia’s already faltering coal industry; new gun control laws put Democrat at odds with an electorate where most voting households own a gun (in the 2018 exit polls, 78 percent of voters said someone in their household owned a gun).

So, on this telling, what is at stake in Manchin’s stand, is less the economics of fossil fuels or the costs and benefits of decarbonization for West Virginia, but the trajectory of party political and class realignment. It is that history that persuades Manchin to cling to the totems of coal and gas, whilst rejecting billions in investment. As the senior representative of one of the poorest states in the Union, he declares himself to be the last bastion against a new culture of entitlement. As Jamelle Bouie concludes it is a “dispute over values as much as — or even more than — a dispute over policy.” Ironically, what an enquiry into the West Virginia roadblock exposes is less the defining importance of actual producer interests – insofar as we can measure them – than the perverse grip of conservative “producerist” ideology over American politics.