Whether we are living through the beginning of a new inflation is uncertain. What is clear is that we are living through a great inflation debate.

I cannot think of a period in recent memory, in which there was so little agreement on likely future trends.

The uncertainty causes real anxiety for policy-makers and the public. Does it amount to a crisis of the authority of economics?

“Nobody Really Knows How the Economy Works” ran the New York Times headline a few days ago. Might this be the opening for a new and better type of analysis? I would not presume to answer that question. But this is a moment to orientate ourselves. Once again, it is a moment for second-order observation, a moment to watch the inflation-watchers.

Why is this moment producing so much controversy and debate?

First there are the issues with the data themselves. When economic disruptions happen, they unleash adjustments that make the disruptions hard to measure. It is a bitter irony. Precisely when you need them the most, the data get difficult.

All the evidence both quantitative and qualitative suggests that the actual state of the economy right now is hard to read. The situation is illegible because different parts of the economy are moving at different speeds and in different directions.

Add to this the fact, that even before the COVID crisis hit, central bank economists were struggling to make sense of what was then a world of lowflation. That uncertainty has carried over to the post-COVID world. If economists struggled to explain low inflation, they now struggle to explain price increases.

There are some commentators, of course, who are only too ready to offer explanations and remedies. Price adjustments are political, inflation is a boogey man with which to scare conservative constituencies. In Europe, in particular, inflation-fear is about.

And politics comes in different flavors. Another, novel component of the current landscape are a brilliant group of neo-Keynesian economists, who have built good connections in think tanks and the media and are skillfully seizing this opportunity to prize open chinks in the armor plates of orthodoxy.

It adds up to a complicated scene. And Chartbook is here to help.

********

I love putting together this newsletter and I love the fact that it goes out free to many readers. If you are enjoying the read and can afford to support the project, please consider signing up for one of the three subscription options.

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Subscribe now

****************

Data

At moments of structural change, it is the weighting schemes that are used to construct price indices that come under pressure. Price index numbers are based on the assumption that the proportion of spending on food, clothing, housing, travel etc remain relatively constant over time. As the FT explains, statisticians face a dilemma as to whether to hold the share of different goods in the consumption basket constant, or whether to adjust to the new circumstances. Transport spending is down, whereas other goods and services are up. Unsurprisingly, the prices for transport services are rising less fast than for everything else. If you adjust the weights to downgrade the lower level of spending on travel, you produce a higher inflation number.

This is one of the effects driving inflation above 4 percent in Germany right now. As Bloomberg explains:

For some technical background check out this NBER paper.

Of course, consumption patterns also vary interpersonally. We all have our own personal strategies for adjusting to COVID. To allow for this problem, the WSJ offered an app that allowed its readers to calculate their own price index.

It this a historic first? America’s leading business newspaper offering us a statistical app to capture our personal “inflation truth”?

Baselines

A far more elementary problem with the inflation indices than the question of weighting, is the question of the baseline that we use to measure inflation.

Following a shock like 2020, using year-on-year measures of inflation produces a long-lasting echo. The exceptionally depressed level of prices in 2020 makes for remarkable inflation readings in 2021.

As Martin Sandbu points out in a typically level-headed piece, all you have to do to eliminate this effect is to take inflation readings month on month. Measured month-on-month inflation in the United States has been decelerating since the spring of 2021.

General v. particular

A point that cannot be emphasized strongly enough is that the conventional “macro” view of inflation defines it as a “general increase in prices”. The emphasis is on the word “general”.

For conventional analysis this assumption is essential.

The point is to distinguish between the underlying causes of price increases. Is the increase in the index the result of a surge in oil prices, driven by the idiosyncratic politics of OPEC+? Or, is the index capturing a widespread increase in prices across the board? The latter might be more moderate in percentage terms, but it might well reflect a more fundamental imbalance in the economy. Macroeconomics – certainly the kitchen sink variety invoked in mainstream commentary – would likely attribute this to an excess of money in circulation, or an excess in aggregate demand, aka “running the economy hot”. Addressing inflation in this more general sense clearly requires a different remedy than addressing an OPEC production cap.

If we take this distinction between general and particular causes seriously, the sort of inflation that most lends itself to macroeconomic analysis is the kind in which all prices move together. A true (macroeconomic) inflation is one where the price index increases and this is attributable to roughly proportional increases across a large number of sub-components. An increase in the overall index associated with a surge in price dispersion is far harder to interpret.

The degree of co-movement or dispersion within commonly-used price indices does not attract as much attention as you might expect. But it is at the heart of our current perplexity.

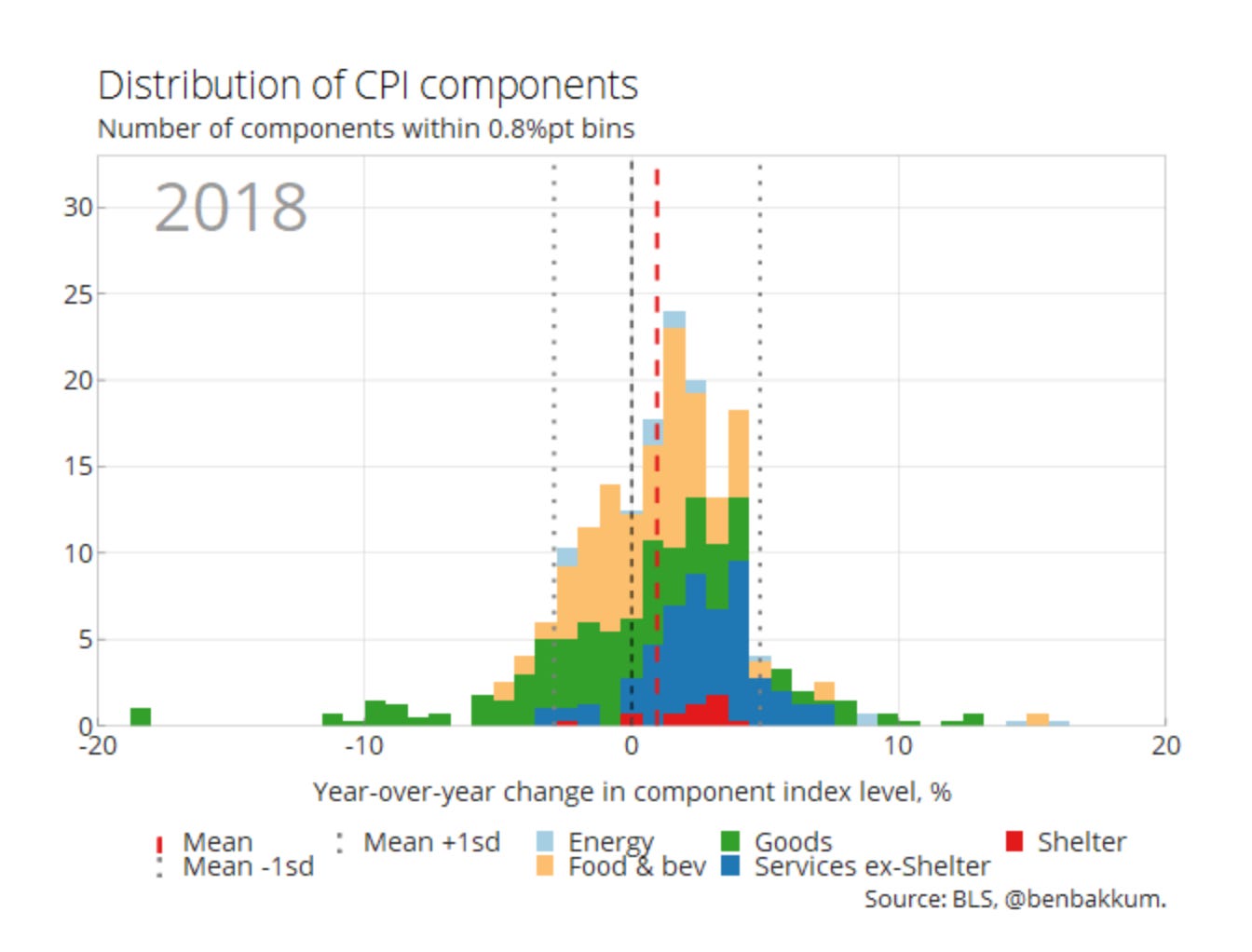

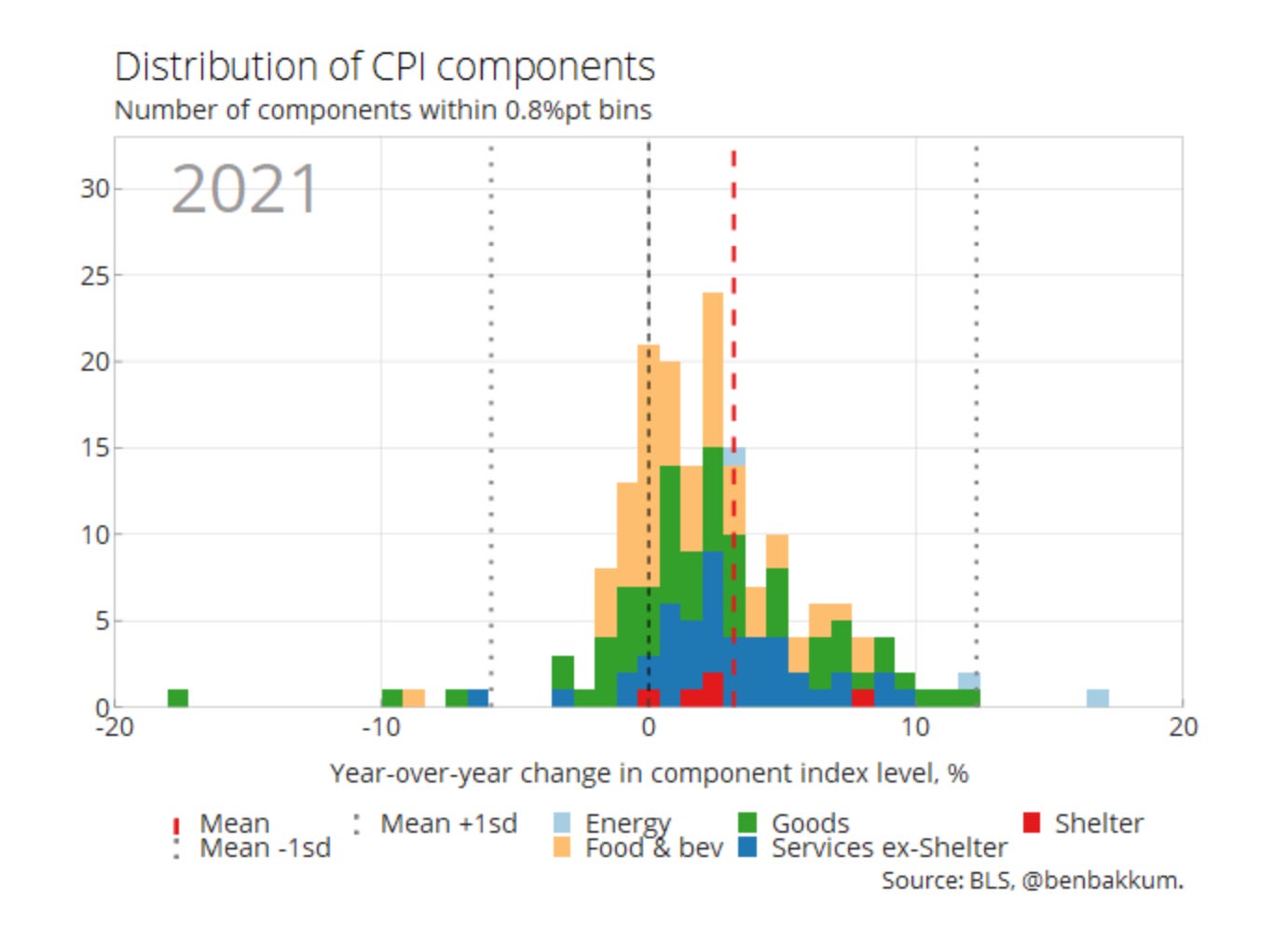

On the dispersion point, this piece by Macro Chronicles is particularly instructive. It shows a considerable increase in dispersion between early 2020 and 2021.

Not only did the average inflation rate (red dashed line) shift to the right between 2018 and 2021, but the dispersion of different inflation rates across the components of the index, as measured by standard deviation (dotted back line), increased dramatically.

There have been many excellent pieces about supply-chain obstructions, the price of lumber etc. But without doubt the most entertaining and weirdly instructive was this by Tracy Alloway on Mayonnaise inflation. You learn more than you may ever want to know about Mayonnaise, but much else besides.

What all these data issues add up to is a simple but important point.

Before getting too worked up about the inability of economists to read our current situation, we should recognize that it is, at least according to these measures, objectively hard to analyze.

Lowflation

Even before the 2020 shock, central banks were struggling to formulate a new approach to monetary policy. First the Fed in August 2020 and then the ECB issued new policy frameworks. Both of their policy moves shifted the balance of policy-making towards a more inflationary position.

This reflected the fact that neither bank had recently had much success in achieving inflation targets of 2 percent. They had tried very loose monetary policy but with little effect. They were afraid therefore of systematically biasing towards lowflation or even deflation.

As is explained in an excellent new Substack by Duncan Weldon, the central bankers will admit that they do not have a good model of inflation.

To make this point, Duncan cites a recent speech by Charles Goodhart at the annual European gathering of policy-makers at Sintra. You can see the video here.

In his typically succinct style, Goodhart laid out the problem: Neither the simple monetary theory of inflation (too much money chasing too few goods), nor the Phillips curve model (too low unemployment driving excess demand) provided much insight into persistent low inflation.

The ECB has just issued a thorough assessment of its consistent tendency to over-predict inflation.

The result, was that central bankers in practice focused less on fundamentals and more on a rather nebulous notion of inflation expectations. If businesses, consumers and workers converged on some rate of inflation that they expected, then their actions, conditioned on that belief, would likely validate that rate of inflation. So inflation control was about anchoring expectations. That in turn explains all the carefully scripted talking that central bankers do.

What to expect when you are expecting (h/t Claudia Sahm)

But how seriously should we take this somewhat circular conception of inflation as driven by inflation expectation? From inside the Fed itself it has been subject to withering criticism by Jeremy Rudd.

Rudd’s paper has taken the internet and indeed the media by storm. He is skeptical that expectations can be measured in a meaningful way or that the expectations we can measure have any meaningful relationship to inflationary processes.

For an excellent appreciation of Rudd’s intervention and its politics see this post by Claudia Sahm. As Sahm points out, Rudd and his colleagues have been warning since 2014 that the Fed does not have a robust inflation model.

“In January 2014—over seven years ago—Alan Detmeister, Jean-Philippe Laforte, and Jeremy Rudd wrote a memo to the FOMC, delivering some bad news about inflation:

The observed evolution of the empirical inflation process over time, the difficulty we [the staff] often have in explaining historical inflation developments in terms of fundamentals, and the lack of a consensus theoretical or empirical model of inflation all contribute to making our understanding of inflation dynamics—and our ability to reliably predict inflation—extremely imperfect.

Fedspeak translation: We don’t know what’s driving inflation. You don’t either. The memo also discusses why inflation expectations aren’t likely a good explanation.”

Unsurprisingly Rudd’s intervention is eliciting pushback from macroeconomists. Among the most forceful is Ricardo Reis. He offers this excellent thread on the issue.

For most surveys of expected inflation, is the median a good statistical forecaster of future inflation? Usually not.

— Ricardo Reis (@R2Rsquared) October 3, 2021

But does this mean that expected inflation does not matter to understand inflation? Absolutely not.

Forecasting is not the same as understanding, or mattering.

The jist according to Rais: inflation expectations may not be good short-term predictors. But that is not surprising. It would be naive to suggest that this makes them unimportant. And this is particularly the case when what is at stake is a regime-shift.

Watch this space!

Inflation politics

At this point, if not before, politics definitely enters the picture. We are engaged in a gigantic live experiment with an unprecedented combination of fiscal and monetary policies and a unique supply-shock. Both in the United States and Europe, the political balance is delicately poised. Unsurprisingly, passions are running high.

The message may be couched in technical language, as in this tweet, but the American Enterprise Institute wants Chairman Powell to tighten policy. From the old center of the Democratic Party, Larry Summers, who once argued for a 3-4 inflation target, has been sounding the alarm.

In Europe, and in Germany, in particular, the scare mongering has been so intense that it provoked the doughty Isabel Schnabel into a vigorous counterattack.

That a German central banker would ever launch a slide like this, calling out not just Bild, but Der Spiegel too, would once have been unthinkable.

Neo-Keynesian opportunity

What makes the current moment particularly interesting is that the inflation debate is not confined to central bank economists and the mainstream of academic economics. There are powerful voices from the neo-Keynesian left-wing, who thanks to connections forged over the last ten years (we need to talk more about the Occupy moment and the New York scene) are gaining a real hearing.

The argument is particularly interesting because it calls into question what exactly inflation is. It hones in on that all-important distinction between inflation in general and price increases in particular. In this particular moment, are we in fact dealing with inflation in general at all? Or, is what we are seeing simply the result of particular causes operating across a variety of different sectors. If the latter then the application of restrictive monetary and fiscal policies to cure it would be disastrously inefficient.

J.W. Mason has spelled out the argument in an interview with Eric Levitz in New York magazine, which I have recirculated several times, and in this more technical blogpost.

One of the things that is particularly interesting about the neo-Keynesian intervention in the current situation is that they are forcing a reevaluation of the historical inflation record.

Debating inflation history.

For those anxious about inflation, the standard references point are the 1970s, when inflation in the US and other rich countries accelerated into the teens and was stopped after 1979 by harsh action by the Fed. But what if our current moment is more like the 1950s inflationary episode associated with the aftermath of World War II and the Korean war?

That question, believe it or not, has made it into the pages of the Financial Times, courtesy of the excellent column written by @rbrtrmstrng

A series of exchanges ensued in which Gabriel Mathy, Skanda Amarnath and Alex Williams outlined an argument that suggested that early 1950s experience should be seen as a reason to take a relatively relaxed view to our current situation and to reevaluate the role of price controls. There was a response by Larry Summers & Nouriel Roubini who are not reassured by the 1950s experience. And a comeback from MAW

The longer former of the neo-Keynesian argument can be found at the Employ America site.

This thread from Skanda Amaranth is instructive:

Overdue thread on the piece @rbrtrmstrng kindly featured and Larry Summers hated…from @gabriel_mathy, @vebaccount, & yours truly.

— Skanda Amarnath ( Neoliberal Sellout ) (@IrvingSwisher) September 24, 2021

Policymaking is based on flaky explanations for the 70s inflation, but they look even flakier when used to explain the 50s 1/https://t.co/SB3VThsb32 https://t.co/62Iq4kNbBQ

Piling onto the debate, Tim Barker weighs in at The History of the Present blog on the true history of Fed policy in the 1950s.

An important intervention from @_TimBarker on the political economy of the 1950s. TLDR: the Fed was hawkish on inflation far before 1979. https://t.co/PzAwCwCnvh

— David Stein (@DavidpStein) September 24, 2021

Taking up the cause, Andrew Elrod in the Boston Review argues: “So long as journalists and thinkers continue to imagine “inflation” as a monolithic historical experience, … a serious discussion of how to think about inflation will be impossible.”

To remedy this problem he offers a fascinating reconstruction of America’s inflation history since 1945, focusing on the episode in the 1950s and 1970s.

The upshot is that inflation is not always a matter of total excess demand. It can also result from sectoral mismatches of supply and demand. If this is the case then restricting aggregate demand is a blunt instrument with side effects that have scarred America’s political economy for the last fifty years.

“It is under the timorous banner of price stability that liberals have acceded to conservative demands for austerity over the last forty years of neoliberal consensus, delivering decades of skyrocketing inequality, stagnant wages, and deteriorating public services.”

“Confronting a period of instability and rising aspirations—historically accompanied by rising prices—requires nothing less than making history. Given the sheer size and influence of the politically managed public sector of our mixed economy, there is no way to pursue economic change without risking some degree of inflation. The true culprit in the winnowing of our political imaginations over the last forty years has been a bipartisan embrace of fiscal austerity and monetary contraction as the first weapons in the pursuit of price stability. … It is the insistence on depressing activity to stabilize prices before all else that has helped to disfigure our society and political life, diminishing our capacity for shaping and guiding our society’s historical development. Until we seriously consider the record of methods for controlling inflation, a future out from under these trends will be foreclosed.”

As Elrod points out, “managed economies across the globe have often resorted to a variety of other tools—temporary price freezes, selective price controls, national wage policies, and targeted investments to expand supply-chain bottlenecks—to respond to rising prices while preserving commitments to more important economic goals. Both Harry Truman and Franklin Roosevelt confronted inflation without hiking rates and tightening budgets, and there is no reason governments can’t manage their economies similarly today. ….”

How price controls help to repress inflation is clear enough. A post-Keynesian specialty is to think of investment, also, as a means of rebalancing supply and demand by easing bottlenecks in key sectors.

Meanwhile, the 1945-1950 inflation meme has spread to the UK, where Neil Shearing of Capital Economics has put out a paper on inflation in the aftermath of World War II. Someone should do an intervention on the West German experience at the same time.

Conclusion?

Does all of this resolve the question of what level of inflation to expect in 2022 and 2023? Hardly.

Personally, I remain committed to the transitory view. Above all, however, it is the process itself that we should welcome and encourage. When we talk about the politics of money this is the kind of debate we should encourage. Open in empirical, theoretical and political terms. Engaged with history in every sense of the word.