Infrastructure bill, reconciliation bill, debt ceiling

After Afghanistan, the Biden administration this weeks seems to be facing another pivotal moment over three interlocking political battles: on the infrastructure bill, the larger $3.5 trillion spending package that actually contains most of Biden’s policy agenda and the debt ceiling.

There is a worst case scenario – unlikely but not impossible – in which, by the end of October, both the infrastructure bill and the more ambitious $3.5 trillion package fail to find majorities, the government shuts down and America defaults on some part of its debt. That is unlikely, but it is not impossible.

Dramatic stuff.

But, say for sake of argument, in the last few days you had had your mind on other things – Evergrande in China, for instance, or the German election, or a day job that involved plunging back into Ken Pomeranz on the “Great Divergence” and Quinn Slobodian on the Habsburg roots of neoliberalism …. say you got to Wednesday and needed urgently to make sense of the mounting drama of fiscal politics in the United States … what would you read?

This morning I turned to two of the smartest progressive journalists and commentators I rely on to help me make sense of US politics and political economy, David Dayen at The American Prospect and Eric Levitz at New York Magazine.

Coming out of the German election coverage, the first thing that struck me in reading their reporting on the US scene, are the striking structural parallel between the two seemingly different political scenes. In the US, as in Germany, politics is now played out on a terrain involving six separate factions.

Biden and the Congressional leadership have to navigate a terrain that involves reconciling three groups within their own camp: first the progressive left, second the Congressional leadership and the bulk of the party, finally “Manchema” – the two “centrists”, Krysten Sinema and Joe Manchin – who through their refusal to fall into line behind the leadership, are holding the entire Democratic agenda hostage.

Then there is the small group of more centrist Republicans who were willing to vote for the infrastructure bill – 18 all told.

Somewhat surprisingly that group included even Mitch McConnell who normally leads the bulk of the GOP in unrelenting opposition to any Democratic party measure.

Finally, there is the Trumpite right-wing of the GOP.

Six groups in all. Familiar in outline from the geometry of European politics.

In Germany, four parties – SPD, CDU, Greens, FDP – are now entering a protracted period of haggling from which will emerge a comprehensive coalition agreement involving three of them, which will then be approved by the party members and implemented over 4 years with the Bundestag majority commanded by the government. The amount of further haggling that is necessary to legislate is minimized, as are issues of blowback from the grassroots, as in the primaries in the US. That is not to say that it is all plain sailing, especially when you consider the complexities of federal governance in Germany and the need to find a majority also in the Federal council. And then at the European level. It will take time. It took 6 months in 2017. Scholz promises a government by Christmas. But, there is a coherence and overall vision to the process.

In the US, the majorities are negotiated for each piece of legislation. Pushing policy across the deeply divided terrain involves continuous, new negotiations and a series of tactical moves.

The Biden team and the Congressional leadership have split Biden’s economic agenda – consisting of the American Jobs Plan (mainly infrastructure) and the American Families plan (more welfare and care-work orientated) – into two separate bills for which they seek to mobilize two distinct majorities.

The infrastructure package, passed in the Senate with Republican votes, is the smaller part. It only adds up to $ 1 trillion because it pairs a minimal package of new infrastructure spending – costed at about $550 billion – with routine renewal of road funding.

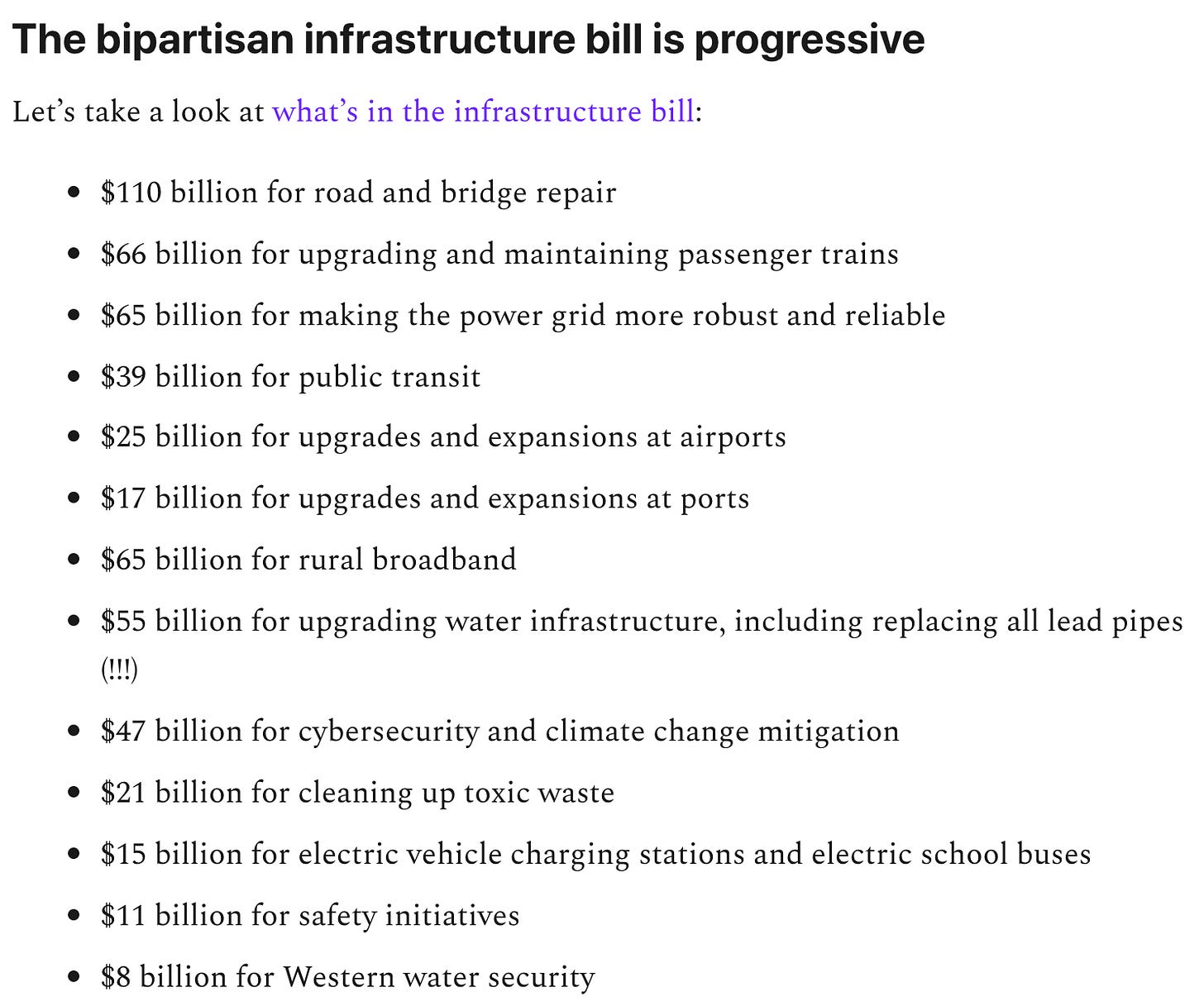

Though limited in scope, as folks like Noah Smith have emphasized, the bipartisan infrastructure bill contains some important reformist agenda items.

Noah Smith’s List:

Source: Noah Smith

They include, for instance, federal funding to take lead out of drinking water and a $100 billion for public transport. But they are modest in scale and fall far short of the reform agenda that Biden promised. They were modest enough to attract 18 Republican Senatorial votes.

To get the consent of the progressive caucus in the House to dividing the program in this way, the party leadership had to promise to link the bipartisan infrastructure bill to a much bigger $3.5 trillion package to be passed through the procedure of reconciliation on the back of the wafer-thin Democratic majority in the Senate, overriding, for this one package, the filibuster rules.

The $3.5 trillion is talked up by Pelosi et al as a historic bill. It would dramatically increase the generosity of the American welfare state. It is also talked up by Manchin and Sinema – the Democratic Party centrist holdouts – as a way of justifying their opposition. The GOP simply denounce it as socialism.

As Dayan and Levitz point out, the only people who make any sense on this are the left, who recognize the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill for what it, in fact, is: a modestly proportioned, watered-down and inadequate compromise, which remedies some of America’s most urgent problems, but comes nowhere near to matching the welfare states of other advanced economies and falls far short of what is needed to address the climate crisis.

It is less even that Biden’s original agenda, which I dissected for the New Statesman back in the spring.

It is not gigantic. Compared to the COVID life support packages it is modest in scale. Annual spending would amount to $350 billion per annum. Furthermore, much of it is covered through tax raises, so the macroeconomic impact will be modest and talk of a runaway inflation triggered by gigantic spending, is silly.

The progressives in the House are digging in to defend the $3.5 trillion, not because they are ideological, but because they are realistic. If they give their votes to the $ 1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure program, they have no reason to trust the willingness of Manchin and Sinema in the Senate, to pass an adequately sized 2nd program through reconciliation. Indeed, Manchin has made clear that he will not countenance $ 3.5 trillion. But neither he nor Sinema have been willing to name an alternative number. Settling on a number is crucial because this is a reconciliation budget bill.

So the progressives in the House are threatening to block the bipartisan infrastructure bill until they get agreement on something close to the $3.5 trillion from the whole Democratic majority in the Senate.

In making this threat, the left are not trying to sabotage Biden’s Presidency, they are trying to save it from the threat coming from the centrists. The puzzle is how to explain Manchin and Sinema’s opposition to the realization of their own President’s agenda. As Politico puts it this afternoon, Biden bets it all on unlocking the Manchinema puzzle.

The polling on both parts of the Biden package are good. The proposed spending addresses obvious deficits in America’s social and economic fabric. The likely return, particularly from spending on families and childcare, is outsized. Given the proposed tax increases, the budgetary arithmetic cannot be described as irresponsible. The proposed tax rates are moderate. The GOP will denounce them as “socialism”, but they will say anything. What the Democratic party left are calling for, is much closer to the realization of the populist agenda that Trump promised but failed to deliver. The spending could easily be sold as such, by both Manchin and Sinema. Instead, they choose to join the red-baiting discourse of the GOP and to position themselves performatively against the left wing of their own party.

One conclusion is that Manchin and Sinema have been bought by donors who oppose higher taxes. Manchin, who owes his wealth to coal, clearly wants to gut the climate elements of Biden’s policy. Vanity is in play. Sinema and Manchin are garnering huge amounts of attention. For Sarah Jones at the Intelligencer, what is on display is the “bottomless emptiness” of compulsive centrism.

One is left wondering why Biden’s political operatives permit this. It is hard to imagine in the hard-boiled era of President Johnson that such disruption would have been permitted. Can it really be true that there is no way either to bribe or coerce these two Senators into falling into line? No skeletons in their closets? No pet project they need funding for? Where are the political dark arts when you need them?

If the Democrats are hobbled over the spending packages, the situation with regard to the debt ceiling is even more frustrating. The debt ceiling itself is an artifact of American politics that goes back to World War I.

Until 1917, debts were authorized by Congress for specific purposes. During World War I, Congress instead set a ceiling and did not require specific authorization for the purpose of debt. In short, the initial intention was enabling of government. In recent decades, the debt ceiling has instead become a political weapon.

It was used twice against Obama – in 2011 and 2013. McConnell has now made clear that he intends to force the Democrats to find a way around him. The Republicans will give the Democrats no votes. Pelosi this week tried to muscle her way around both the Democratic Party left and the Republicans, forcing them to back a measure that would tie the debt ceiling to the road-funding component of the bipartisan infrastructure package. That backfired.

As Dayen notes:

“Democrats can pass a debt limit hike with 50 votes through budget reconciliation. It’s just a bit of a pain to do it, because they didn’t put the debt limit in the original budget resolution instructions.” It also exposes them to ambush by the Republicans who might “boycott a key Budget Committee hearing so they can get the fix on the calendar.”

Other more radical options have been ruled out, such as having the Treasury mint a large denomination platinum coin, or simply ruling that “default on public debt as unconstitutional, which, given the 14th amendment, it arguably is.”

Clearly, the Democrats could “could just end the legislative filibuster anytime they want and repeal the debt limit” or they could pass by reconciliation a measure that simply sets the debt limit at whatever the national debt is.

“If McConnell is telling Democrats to fix the debt limit on their own, they should actually fix it by eliminating it.”

In the end, it is likely that deals will be done. It is likely that the infrastructure bill will pass, plus all or part of the $ 3.5 trillion package. It likely also that the debt ceiling will be raised and America will avoid default. But it is hair-raising. And it will become more so as we enter the full intensity of the mid-terms in 2022.

It is also clear that what is emerging is, in no way, a transformative program. It is important. It is progressive. Little of it would be happening but for the imagination of the left and its dogged determination. But what is emerging lacks the scale and the institutional ambition to be transformative.

As Levitz points out, in institutional terms, Biden is a step back even from the modest ambition of the Obama Presidency. He is not attempting a comprehensive fix on the environment, or a major health care reform. The shock of 2020 has not added a comprehensive reform program for unemployment insurance to the agenda.

One of the reasons why the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill is so crucial is that is seen by the labour movement as the best hope of making progress on the PRO Act proposals to strengthen the power of collective bargaining.

As one lawyer for the employer side put it: “These are cataclysmic questions of the most fundamental policy that have gargantuan implications for … this country. And this type of fundamental policy change is being done using a backdoor approach.”

One may disagree with the spirit of his remarks, but on substance it is hard not to agree. The question is of course why. And that question points us back to the 6 factions in American politics and the power play between them.