Watching the world watching China’s Evergrande crisis

As John Authors argues in one of his latest columns, there is little doubt that anxiety about the Evergrande crisis has been moving global markets in recent days, though there are plenty of other stories to worry about.

This latest incident is one more demonstration of the eerie fact that in the first decades of the 21st century, the trajectory of global capitalism has come to hinge on the development of China, a country ever more clearly in the grip of a one-party communist regime.

As the FT reports, even in recent months, big Western money was flowing into Evergrande.

As late as August, BlackRock bought five different Evergrande dollar bonds for its high yield funds. Across its huge portfolio, BlackRock’s total exposure runs to perhaps $400 million. As far as BlackRock is concerned that is a drop in the ocean, but it is indicative of the fact that China is a story, “you just have to be part of”.

As the FT reminds its readers: “China has long been the biggest engine of global prosperity, contributing 28 per cent of GDP growth worldwide from 2013 to 2018 — more than twice the share of the US — according to a study by the IMF.”

Watching the China watching

Not only is watching China something we have to do. We are actually at a point where how we observe China, how we stand in relation to China has come to define how we relate to the world and who we are in the eyes of others.

In other words, we not only watch China, but we watch how we watch China.

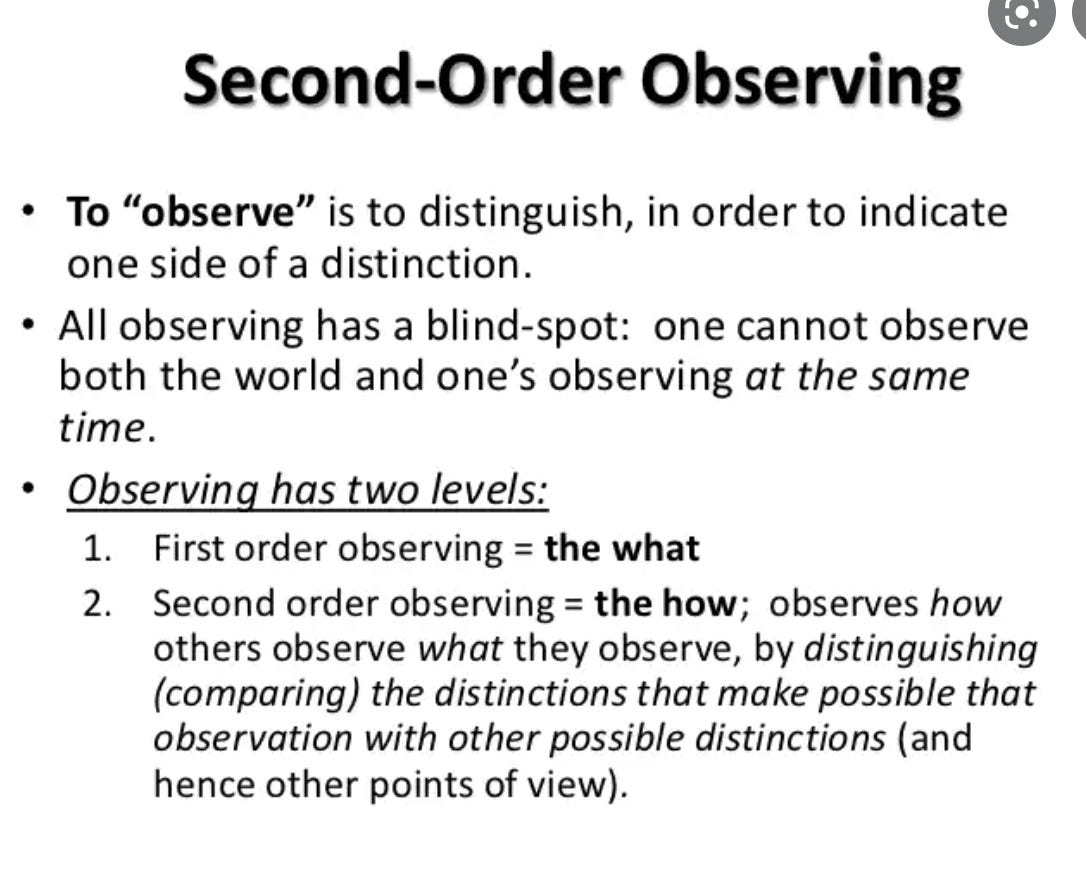

In Niklas Lumann’s terms we are in the realm of second-order observation.

In Shutdown, my book on the corona crisis, I highlight the way in which the Chernobyl analogy served to cloud the outside view of events in China in January-February 2020. Wuhan, it turned out, was not a provincial town deep behind the Iron Curtain in the 1980s Soviet Union.

Today, faced with the Evergrande financial crisis what do we do? The first analogy that has been readily to hand is Lehman.

Even one of China’s leading business papers, Caixin, resorted to the Lehman analogy in its excellent “warts and all” expose on Evergrande.

The Caixin report is highly recommended. It is at least as meaty as anything published by any Western news outlet. But, as Bill Bishop points out, this headline was confined to the English edition of Caixin.

Contagion?

Of course, there are similarities between the two cases that come to mind:

Evergrande is like Lehman in that it has speculated on real estate. It has a lot of debt spread across the entire Chinese economy and Chinese society. It is opaque. It is worrying.

And the Lehman analogy, unlike the Chernobyl analogy, does at least express a sense of entanglement on our part with the events in China.

Chernobyl happened to the Soviets. Lehman happened to “us”.

But is Evergrande really Lehman? Closer examination suggests that the Evergrande crisis is not like Lehman at all.

The question of contagion is what concerns the markets. In the Evergrande case, there is some dispute between market insiders, but the majority of commentators seem to have decided that is not a Lehman-style issue.

Western observers are quick to point out that since China’s banking system is ultimately state-backed there is no real risk of panic spreading.

You might think that this was reassuring. From the aftermath of the Lehman crisis, TARP etc you could draw the conclusion that ultimately the Western banks are state-backed too and the sooner this is made explicit in a big crisis, the better. But that is not generally the gist of the Evergrande commentary.

The point is that China is different. “CCP-controlled. State-owned. Rules are different.” As Robert Armstrong succinctly puts it: “The whole point of China’s mostly self-contained financial system is that most of the debt is owed by one part of the country to another. The party is in control of all of those parts, and so the debt is, essentially, whatever the party says it is.”

This is a way, not of expanding the argument, not of turning the mirror back on the West (is debt in the West now owed by one part of the country to another?), but of shutting the train of thought down.

After all, market players in the West have other things to worry about. So long as there will not be a general meltdown that is all they need to know. Evergrande is not Lehman because China is different. Great. Time to move on.

Controlled Demolition

That quick move to dismiss contagion is convenient also because it avoid wrestling with another more unsettling difference.

The more basic difference between Lehman and Evergrande, is that crisis in China was deliberately brought about.

Unlike the disastrous chain reaction at Lehman, this is a controlled demolition, deliberately triggered by the regime.

Beijing is doing what critics have been asking China to do for a while – to deflate the housing bubble. It is doing what the West did not do in 2007-2008, i.e use regulatory intervention to manage a hard landing short of outright crash.

The backdrop as is spelled out in this excellent episode of the Odd Lots podcast with Travis Lundy, is the entanglement of the system of private property and local government finance that was created during the reform process in the 1990s.

In 1995 public finances were reorganized and the ability of local government to borrow was curtailed. That was followed in 1998 by a land management law that allowed land to be sold to private parties. Thus, local government discovered that it could finance itself by selling land and raising debts through off-balance sheet SPV that used land as collateral. Property developers became giant hoarders of land, which was then developed and sold to households who lacked other remunerative ways of investing. “So you have the local governments in bed with the real estate developers who are all kind of aligned with seeing property prices go up because they own the land banks, which they bought five years ago. And then all of the populace, you know, that’s their savings vehicle. Obviously they want the value of that saving vehicle to go up. So, no one’s really interested in seeing prices go down, except for those people who don’t have real estate already.”

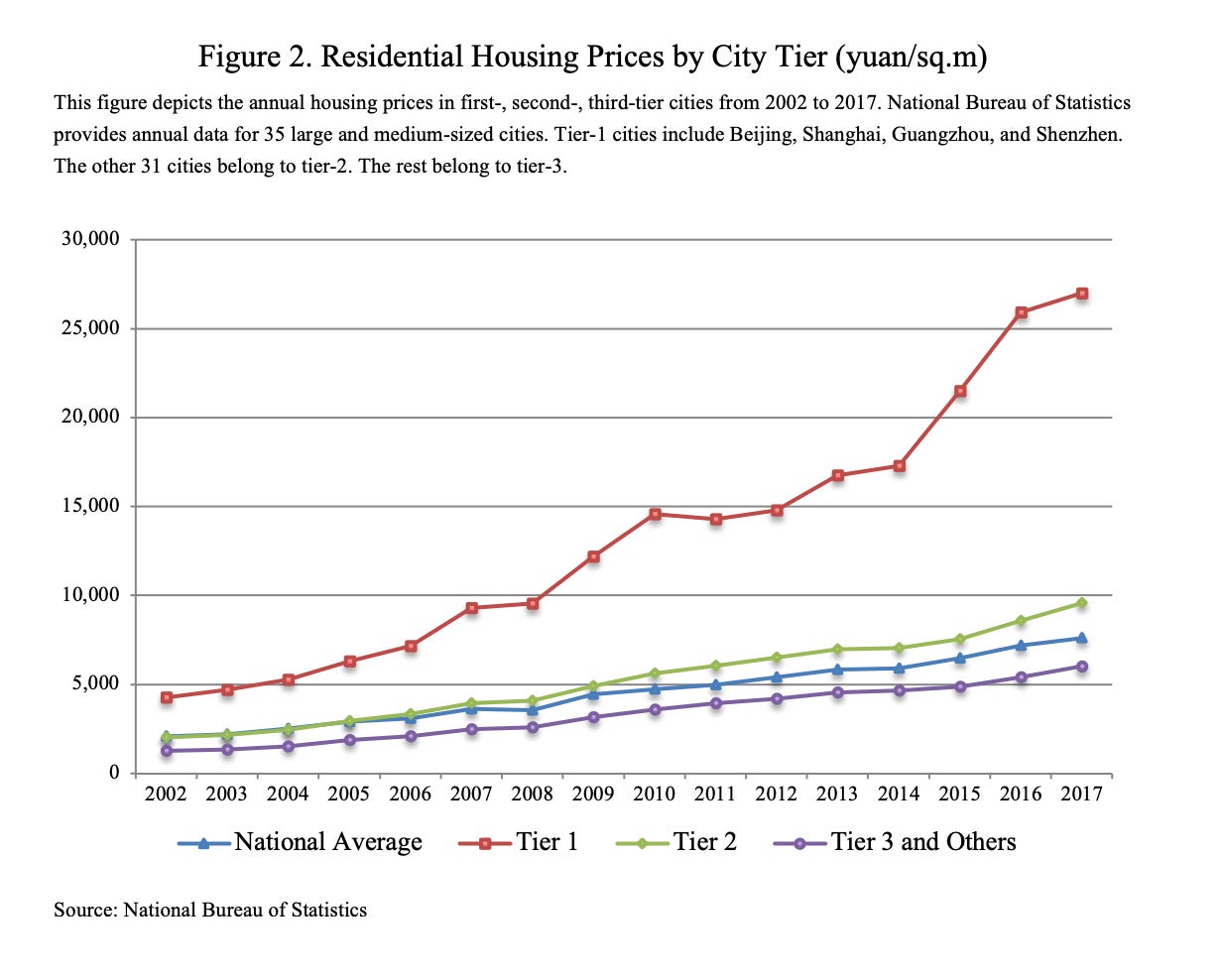

Home-ownership rates are staggeringly high in China. But, there is also a severe dispersion in property prices, which creates a two-tier system amongst property owners.

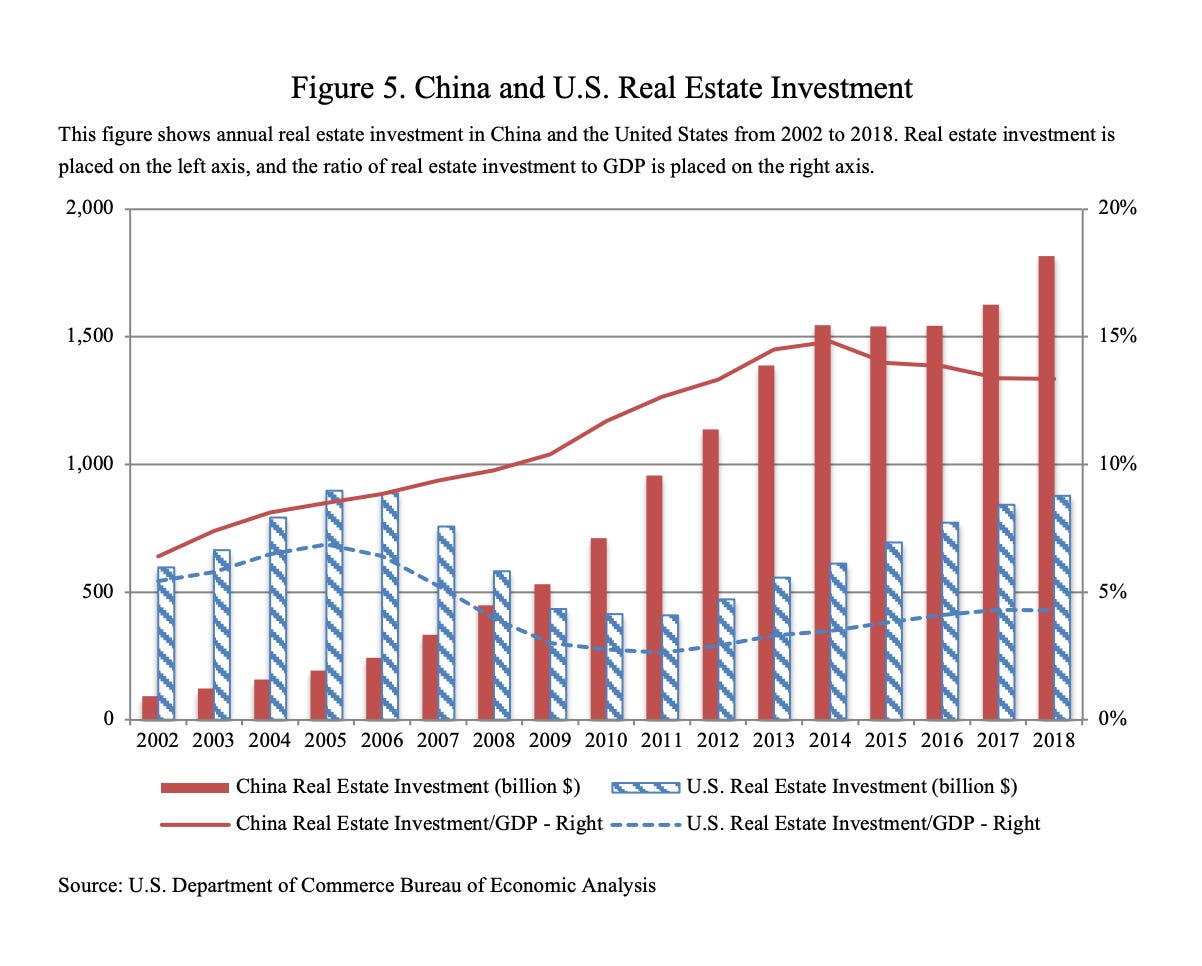

Source: Rogoff and Yang (2020)

As a private developer without direct state backing, Evergrande secured its position by being willing to invest in the second-tier cities and built a dense network of political connections there.

It was a key node in an entrenched network of capital, private interests and political connections.

In 2020 Kenneth S. Rogoff Yuanchen Yang came out with an important NBER paper summarizing the scale of the problem.

In terms of scale of investment, the Chinese real estate and construction sector is at least twice the size of its US counterpart and three times as important in relation to GDP. In cities it accounts for c. 17 percent of employment. Its share in local public revenue stands at about 1/3. Real estate accounts for c. 80 percent of household wealth in China, versus a share of around 30 percent in the US.

Strategic intent

The campaign to rein in this gigantic growth machine began in earnest in October 2017 when Xi gave his speech to the 19th Party Congress with the famous line: “houses are for living in, not for speculation”.

In November 2018 the PBoC red-flagged the huge level of debt in private property developers like Evergrande. At that point the interest rate at which Evergrande borrowed popped to 13 percent. No one could be in any doubt about its status as a high-risk business.

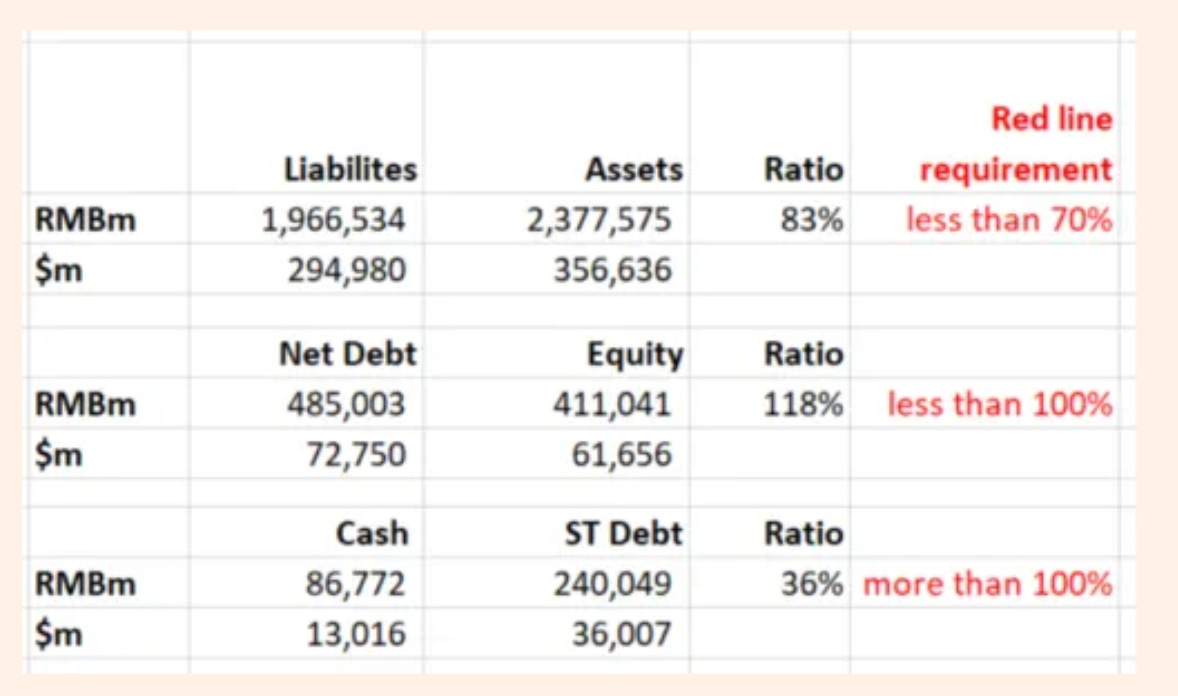

In August 2020, the Chinese regulators announced their three red lines, imposing tough new financing limits on property companies. As Robert Armstrong’s compilation makes clear, Evergrande ran foul of all three.

New funding was effectively cut off and a cat and mouse game ensued between Evergrande, its creditors and the authorities.

There can be little doubt about the overall strategic intent of the regime. As Bill Bishop remarks: “Xi set out three tough battles for the government- poverty, pollution and financial risks. Significant progress has been made on the first two, but the battle against financial risks has lagged. Perhaps Evergrande will mark a turning point in that battle, “

In an important essay for Carnegie, Michael Pettis focuses on the concerns of the regulators: “By clamping down on leverage among property developers, Beijing was hoping to accomplish at least two things. First, this measure was intended directly to address surging debt among one of the most indebted sectors in China’s economy. Second, the hope was it would help stabilize the housing market by constraining what regulators believed was one of the sources of speculative frenzy, the debt-fueled competition among developers to scoop up as much land as possible.”

For Pettis, the economist, the problem is the structure of lending: “There was very little credit differentiation in the lending markets. Banks, insurance companies, and bond funds fell over each other to lend to large, systemically important borrowers. Moral hazard, in other words, underpinned the entire credit market. That is why Chinese regulators have decided to have a showdown with creditors over Evergrande. By convincing lenders that they will no longer stand behind large Chinese borrowers, they are trying to transform the country’s financial system by making Chinese lenders more reluctant to fund nonproductive investment projects.”

As Pettis points out, Xi has accompanied the push over the summer of 2021 with a key paper in the party’s theoretical journal Qiushi on “quality growth”.

The recent focus of industrial policy on high tech and green growth fits squarely with this emphasis.

So, if we set aside the misleading analogy to the unplanned catastrophe of Lehman, and see Evergrande as an exercise of deliberate policy, the question is whether Beijing’s strategy will actually work.

Risk 1 – There are hidden issues & Beijing is not fully in control of the situation.

As Bloomberg reports: “China has left the market on tenterhooks,” said Zhou Hao, senior economist at Commerzbank AG in Singapore. “Traders can’t figure out Beijing’s thoughts on how the Evergrande crisis will be resolved and how weak the economy is allowed to be. In the near term, the PBOC will inject sufficient short-term liquidity to maintain ample cash supply.” What if the crisis-managers misjudge?

Or, as Bill Bishop remarks: “This silence looks like they are still working through the magnitude of the problem and so are not willing to make any significant statements until they have a fuller grasp of the extent of the mess and a plan to resolve it. Not comforting if that guess is correct …. As this newsletter has discussed several times, I would not be confident that the regulators have a full understanding of all the Evergrande liabilities and interconnections with other firms. Xu Jiayin has been masterful, at least until now, at obfuscating the full extent of Evergrande’s debts …. ”

Bad as this could get, if we assume that the regime can ultimately contain financial contagion, the work-out may be messy, but it is manageable.

Risk 2 Financial distress will spread

Pettis in his Carnegie essay points to a more fundamental set of difficulties. If Beijing is serious about resetting its entire financial model then it faces a huge task: “To erase the assumption of moral hazard would mean wiping out the structural underpinnings of the country’s credit markets. Financial markets, in other words, would have to undergo a major repricing of credit and a corresponding reallocation of credit risk portfolios. The problem is that there would be a vicious circularity to this process. Bankers wouldn’t know how to restructure credit portfolios until they understood what the restructured market would look like. But knowing this would require answers to questions like: Who will still be able to access credit? How much and in what form? At what prices, and what guarantees, if any, will remain? But, of course, they could only know what the restructured market would look like after they have collectively restructured their credit portfolios. Among other things, this means that individual lenders should rationally wait for all other lenders to restructure their portfolios before doing so themselves.”

This would imply a prolonged credit stop that could have disastrous effects.

Furthermore, as the credit system becomes glued up, the risks begin to spread. As Robert Armstrong remarks: “The ugliest number on Evergrande’s balance sheet is not captured in the red lines ratios at all. It is, instead, Evergrande’s Rmb951bn ($142bn) in short-term payables.” All those contractors with unpaid invoices will find themselves under financial pressure and will pass that on to their creditors.

This is what Pettis calls “financial distress”: “In finance, indirect financial distress refers to adverse changes in the behavior of stakeholders who are responding to a rising risk of insolvency, with this behavior in turn further raising the probability of insolvency. Financial distress behavior is a highly pro-cyclical process during which an incremental deterioration in credit conditions suddenly begins to accelerate, so a linear decline in credit becomes nonlinear. Which is a big deal that they do not seem fully prepared for …. ”.

To address this risk of spiraling credit contraction, Pettit urges rapid and decisive action: “Property purchases have fallen very quickly, and retail investors in wealth management products have already organized visible protests in many cities. Meanwhile, suppliers and contractors are reeling from potential losses, and since many of them have been paid in real estate, they are likely to try to sell these assets as quickly as possible to satisfy their own liquidity needs. This cannot help but disrupt the real estate market further. What is more, Evergrande’s 200,000 employees, not to mention hundreds of thousands of employees at other property developers and at affected upstream and downstream businesses, are probably beginning to feel fairly aggrieved. Before financial distress spreads further throughout the economy, regulators must address this as rapidly as possible by drawing very clear lines about what will and what will not be rescued so as to suppress the uncertainty Evergrande has created in the economy.”

Risk 1 is transient, risk 2 is more serious because the real estate sector is so large.

Clearly, pricking the real estate bubble is a hugely delicate political operation with vast ramifications for the economy as a whole.

The question is, can the political economy of China, not just the regime but households, regional governments etc adjust. Will other sources of growth emerge? Will the regime stick the course?

One line argues that the real estate impasse reveals deep structural difficulties connected to demography and the exhaustion of easy sources of growth.

As a piece in the FT by James Kynge and Sun Yu comments:

”China’s population is hardly growing. In 2020, only 12m babies were born, down from 14.65m a year earlier in a country of 1.4bn. The trend may well become more pronounced over the next decade as the number of women of peak childbearing age — between 22 to 35 — is due to fall by more than 30 per cent. Some experts are predicting that the birth rate could drop below 10m a year, throwing China’s population into absolute decline and further dampening demand for property. Houze Song, an analyst at Chicago-based think-tank MacroPolo, says the situation is exacerbated by the phenomenon of “shrinking cities”. After around three decades during which hundreds of millions of people left their rural villages to settle in cities, the biggest migration in human history has now dwindled to a trickle. About three quarters of the cities in China are in population decline, says Song. “A decade from now, even assuming that some people will leave for growth cities, more than 600m Chinese citizens will still live in shrinking cities.””

This is a version of the “middle-income trap” diagnosis of China’s development problems.

Another line, is that regime will not stick the course in deflating the real estate bubble, because it hurts too much. The entire system is too wedded to growth targets. These require repeated stimulus to “top up” natural growth with a discretionary policy-driven element. That is most easily done by investment and that is concentrated in real estate. This is clearly the concern of Michael Pettis, who has long been arguing that China’s growth model is unsustainable.

Similarly, Bill Bishop remarks: “Perhaps Evergrande will mark a turning point in that battle, or perhaps the problems run so deep that they will have to back off from the most stringent efforts to rein in real estate, as they have had to do after previous attempts to lance the festering economic and political boil that is PRC real estate.”

But what about a third possibility? What if it actually works?

What if, along with assertion of dominance over tech, throttling of steel industry and push to end coal finance this is actually what a shifting of economic gear looks like?

I dont have a crystal ball or the insight of the real China experts, but in watching the China watchers, it is striking how rarely this question is posed.

It is possible that Xi and the real estate bubble are different. It is possible that they mark some point of culmination. But as I argued in a piece in Noema, drawing on the work of political economists like Victor Shih, the repeated pattern of China’s development since the 1980s has been one of avoiding crisis by backing away from the brink.

Contrary to many predictions, the network of interest groups around the party in China seems, so far at least, not to produce either paralysis, or wars of attrition. Even before Xi, the regime showed a capacity to switch between growth regimes and macroeconomic settings.

And is this not the ultimate strategic aim? Is ultimate prize not the growth rate or political stability per se, but the autonomy of the regime? After all, the aim is to uphold the capacity of the CCP to shape China’s future for the next century.

A note on Chartbook

I love putting together this newsletter and I love the fact that it goes out free to many readers. But if you are enjoying the read and can afford to support the project please consider signing up for one of the three subscription options.

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.