How a sudden stop threatens to compound a humanitarian and political crisis.

“It’s not the fall that kills you. It’s the sudden stop.”

Back in July I was drawn into the Afghan crisis by the shocking question: “What do you do if you can see the end of your world approaching? Do you flee? Do you resign yourself?”

One month on I fear that what we are watching is the lid of the coffin closing, the earth raining down on a society being buried alive.

There is the threat of draconian Taliban rule, but that is compounded by the economic and the financial situation facing Afghanistan in the wake of the foreign evacuation.

As I put it in a short piece published in Foreign Policy Friday: “The Taliban may threaten Afghanis’ freedom and rights, but it is the abrupt end to funding from the West that jeopardizes Afghanistan’s material survival.”

The Taliban must be held responsible for their violation of human rights, but if the Western powers treat access to Afghanistan’s foreign exchange reserves and financial aid as a means of disciplining Kabul – as was recently suggested by the G7 – it is we who are putting in jeopardy the survival of the Afghan population and what is left in Afghanistan of a modern economy.

My brilliant friend Nick Mulder (Cornell) is about to publish an important book with Yale University Press about the history and politics of sanctions.

Nick’s take on the history of sanctions is highly critical. He does a brilliant job explaining the remorseless logic of liberalism’s preeminent coercive weapon. Indeed, he places it in continuity with the logic of nuclear deterrence. It is going to be a widely debated book.

Whether you are for or against the sanctions weapon, if there was ever a case that revealed the pitiless violence of liberalism’s preeminent means of international coercion, it is Afghanistan. Not only is the majority of the Afghan population intensely vulnerable. They are amongst the poorest people on the planet. But the bit of Afghan society that has seen some economic development, was reared, educated and financially animated by the US-led coalition over the course of the twenty-year intervention. Cutting off finance to Afghanistan is not like sanctioning an autonomous, free-standing, self-sustaining society. We are deliberately throttling the life support of an organism that we in large part created and remains critically dependent on us. If the Taliban’s aim is to demodernize Afghan society then we will be doing their work for them.

At their most cynical, sanctions are a deliberate attempt to trigger an ungovernable humanitarian crisis, which will undermine Taliban authority. That would be a crime against the millions who will suffer the effects including millions of children. The only circumstance under which the sanctions serve in a more measured way as a strategic tool, is if the Taliban have discovered that they do not, in fact, want to demodernize Afghanistan, but have an interest in maintaining whatever economic development has taken place. If that is the case, it is all the more perverse for us to be the force crushing the elements of modernity that we ourselves have helped to foster.

Appeals for generous funding have been made in recent days amongst others by Saad Mohseni and by Ajmal Ahmady. We should support them.

In this newsletter I want not only to revisit some of the economic and social data that show how acutely dangerous this crisis is. I also want to make an analytical distinction between three different crises.

First there is the political crisis of Taliban conquest and seizure of power.

Then there is the looming humanitarian crisis. This results from Afghanistan’s chronic poverty compounded by war and environmental shocks. According to the World Food Program, half of Afghanistan’s population is in need of assistance. Millions of children are malnourished. The harvest in 2021 has been devastated by drought.

On top of those threats, Afghanistan’s macroeconomic situation is menacing. The bit of Afghan society that was not dependent on basic agriculture or immediately reliant on foreign aid – let us call it “urban Afghanistan” for short – lives in an economy that is fueled by foreign payments. That funding is now abruptly halted and is being made into a diplomatic weapon. The idea seems to be to release it only on condition of “good behavior” by the Taliban. The consequences for urban Afghanistan will be dire.

Before getting into the nitty gritty, it is worth taking a brief detour into history. Timothy Nunan (FU Berlin), who wrote a brilliant book on the history of rivalrous modernization projects in Afghanistan, has given us his historical perspective on the current crisis in an excellent essay in Noema.

As Nunan points out, both the common clichés about Afghanistan – medieval and/or graveyard of empires – obscure the fact that the country has, in fact, been a laboratory of modern political experimentation.

“Yet, the “graveyard of empires” narrative obscures as much as it illuminates. It makes Afghans bit players, rather than protagonists, to their own history. And it fails to explain why Afghanistan has been at the margins of geopolitics for much of its modern history, in particular for much of the twentieth century. The Afghans won their independence from the British in 1919, only to discover that with liberty came an end to British subsidies. New state monopolies and tariffs allowed Kabul’s rulers to gain a measure of economic self-sufficiency. Fundamentally, however, the resources inside Afghanistan’s borders could not pay for the costs of governing the space within those borders.

Thus was born the real pattern to modern Afghan history, namely that of Afghan elites appealing to foreigners to subsidize and build up the Afghan state. Afghanistan became a field onto which outsiders could project norms of statehood, development and modernity. Ottoman and Indian Muslim technocrats flocked to Afghanistan to shore up one of the Muslim world’s few independent states with constitutions, officer schools and printing presses. Like their German and Italian successors in Kabul, these foreigners sought not to conquer Afghanistan, but rather embed it in a coalition of states that could challenge the British-dominated interwar world order.

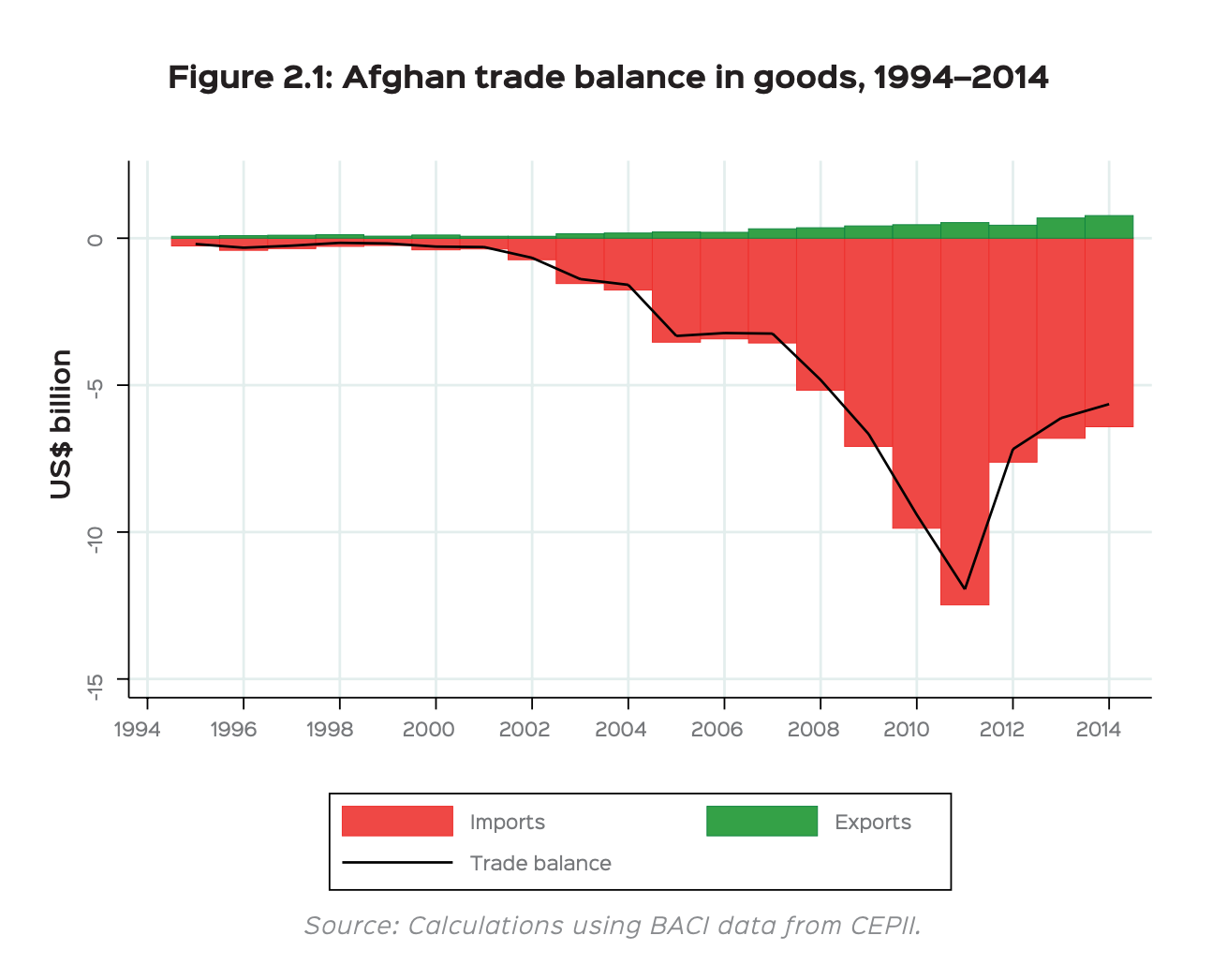

This passage really struck me because this is exactly what we see in Afghanistan’s economic balance of the last thirty years.

Source: World Bank

Afghanistan in the 1990s, during the period of warlord battles, habitually ran a trade deficit, but it was small . It was when a new elite was installed in power after 2001, with new foreign backers that the trade deficit blew out. One could hardly ask for a clearer demonstration of Nunan’s diagnosis.

Recently, the deficit has hovered somewhere between 25 and 30 percent of GDP. This is a huge imbalance, which creates a corresponding risk of a sudden stop.

To be clear, to run a trade deficit is not necessarily a bad thing, especially for a very poor country. We tend to think of imports as an economic “bad”, whereas exports are considered an economic “good”. Of course, there may be some imports that are frivolous or undesirable. Naturally it can be a source of pride if a country makes things or offers services that the world wants to buy. But it is not surprising that a poor country cannot offer these. If it could, it would not be poor. It is almost definitional of modernity that in a poor country the population’s wants should exceed their ability to satisfy them. In this sense having a trade deficit is a sign that life has a modern pulse.

International trade is not an Olympic sport in which the country with the biggest trade surplus wins the gold medal. If you are looking for an analogy it is better to think of the economy as a metabolism for which imports serve as the food or fuel. They are essential to preserving the society or economy in being. Cutting them off risks metabolic collapse, in other words a severe recession. That is what is threatening urban Afghanistan in the current moment. That economic shock comes on top of the gigantic humanitarian crisis of chronic malnourishment and poverty – amplified in recent years by the shocks of mounting civil war and drought.

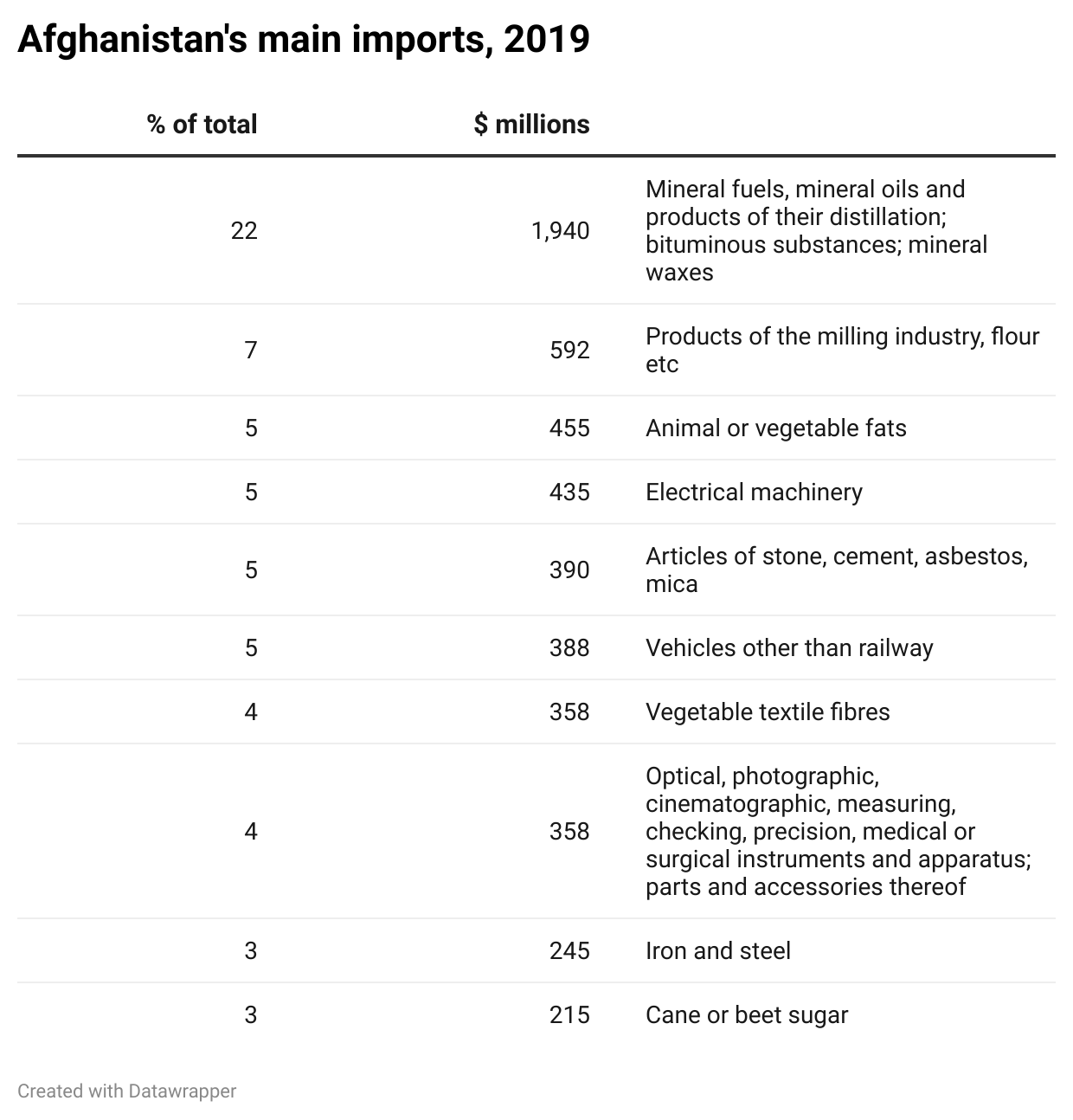

What kind of things does Afghanistan import?

Source: Trend Economy

The size of these numbers is daunting. In 2019, a year of particularly grievous trade imbalance, Afghanistan’s export earnings would have been sufficient to pay for no more than half of its bill for imports of mineral oil products and that would leave nothing to cover the rest of its needs.

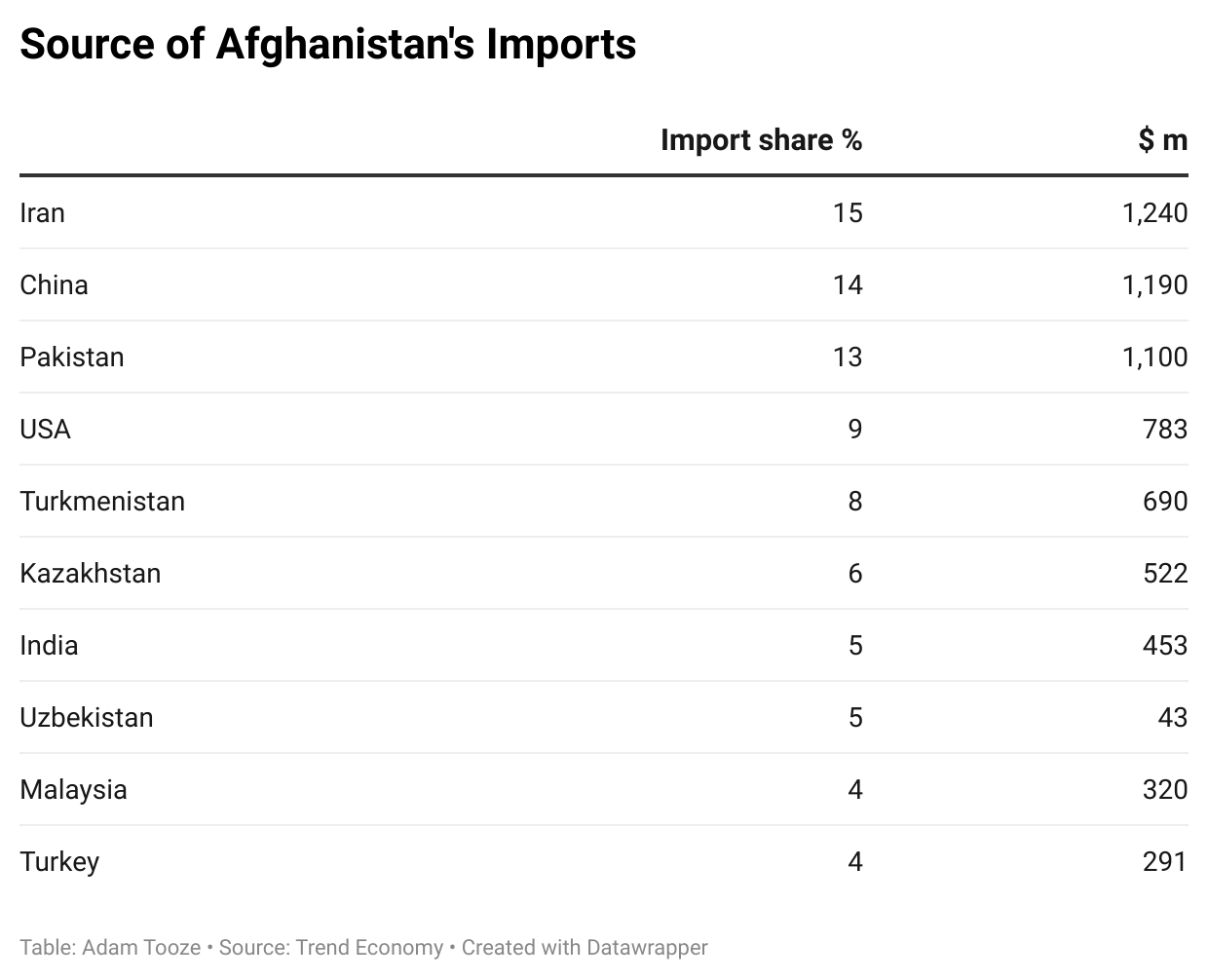

Where do Afghanistan’s imports come from?

Iran is, presumably, the main source of petroleum products.

Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbors are critical as suppliers of food (flour) and electricity. 70 percent of Afghanistan’s electrical power is imported and the annual bill comes to around $270 million. Without that power, the lights literally go out.

In Afghanistan, where it has generally been too dangerous to conduct a door to door census, we estimate the pace of urban development by counting lightbulbs from space. Specks of light shining in the dark suggest that roughly 10 million people live in Afghanistan’s cities.

What foreign funds have been covering is the yawning gap between the foreign inputs to Afghanistan’s rapidly growing society and what it is able to pay for with its very limited exports of gold and agricultural produce.

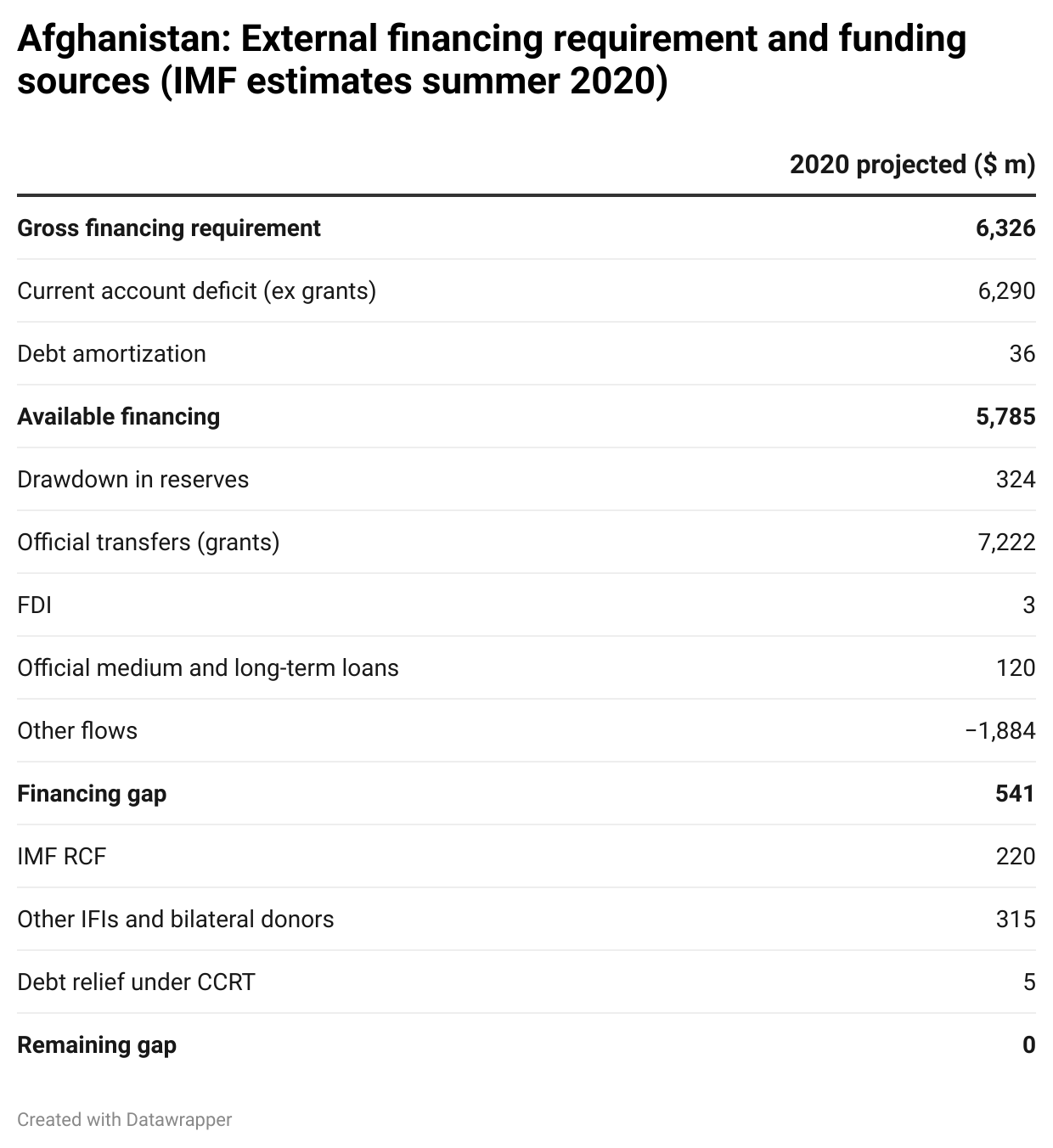

Earlier this year the IMF prepared this estimate of Afghanistan’s foreign funding needs and how they would be met.

The key items in this balance are the current account deficit of $6290 m (in Afghanistan’s case largely identical with the trade deficit) and the official transfers (grants) of $7222 m.

If that $ 7 billion in funding is cut off, it will not be Taliban oppression alone, but a dramatic economic collapse that will bring life as Afghans have known it in recent years, to a halt.

What economists call a “sudden stop” can befall any economy heavily dependent on external funding to support a large trade deficit. “Export triumphalism” aside, this is in fact the main reason to worry about running a large trade deficit. A sudden stop can be extremely painful and destabilizing. It is the simplest way to think about the economic crisis that felled the Weimar Republic in the early 1930s.

This sudden stop is distinct from Afghanistan’s chronic poverty and the humanitarian crises triggered by civil conflict and drought of recent months. But though it may be distinct, the economic and financial crisis will interact with and compound those other problems.

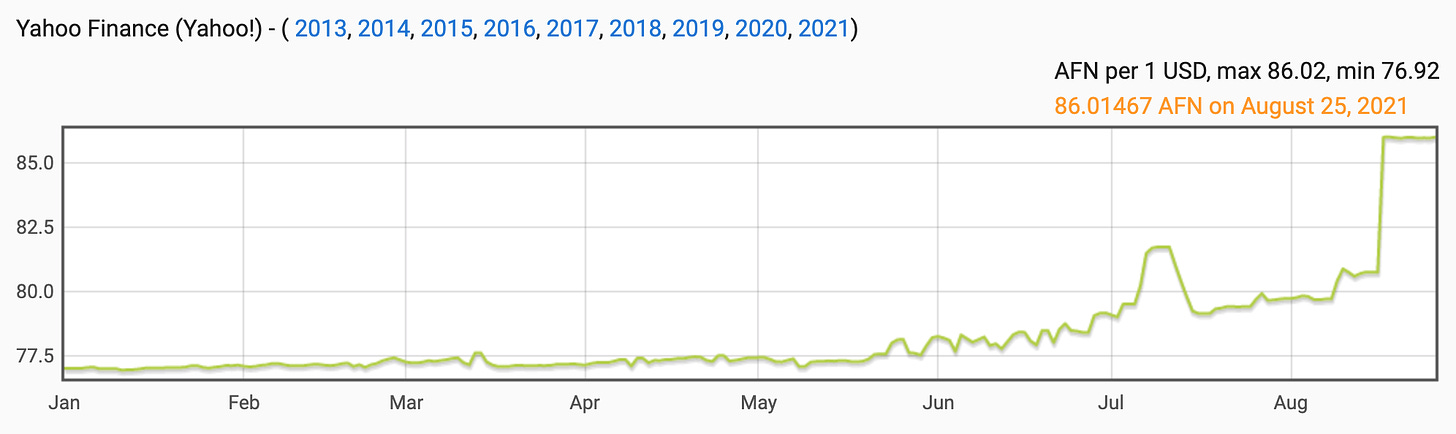

One of the critical linkages is the exchange rate. Afghans, at least in the cities, are acutely aware of their country’s precarious financial situation. The banks have been closed for more than a week. Western Union has closed its offices, shutting off flows of remittances that normally account for 4 percent of Afghan GDP. The US authorities halted the last shipment of cash dollars to Afghanistan ten days ago and the outgoing central bank governor and his staff did their best to concentrate what currency they could lay their hands on in Kabul. The Afghani banking system will likely be subject to panic attacks.

The obvious precautionary response to a situation of impending doom is to sell Afghani and buy whatever dollars are to be had. The Afghani plunged on August 17. Since then it is not moved much. This is surprising. I imagine that not much currency trading is going on in Kabul right now. Certainly, one would expect further deterioration in months ahead. And if we can figure that out, so can the currency traders in Afghanistan. So, it may happen fast.

Source: Free currency rates

A dramatic depreciation in the currency is an alarming prospect because it raises the price of imports and stokes inflation, unleashing a struggle for survival between more and less well-off Afghans.

Acute famines generally result from shortages of food triggering a scramble for necessities, speculation and spikes in food prices, which kill the poorest. Those are the elements we can already see at work in Afghanistan.

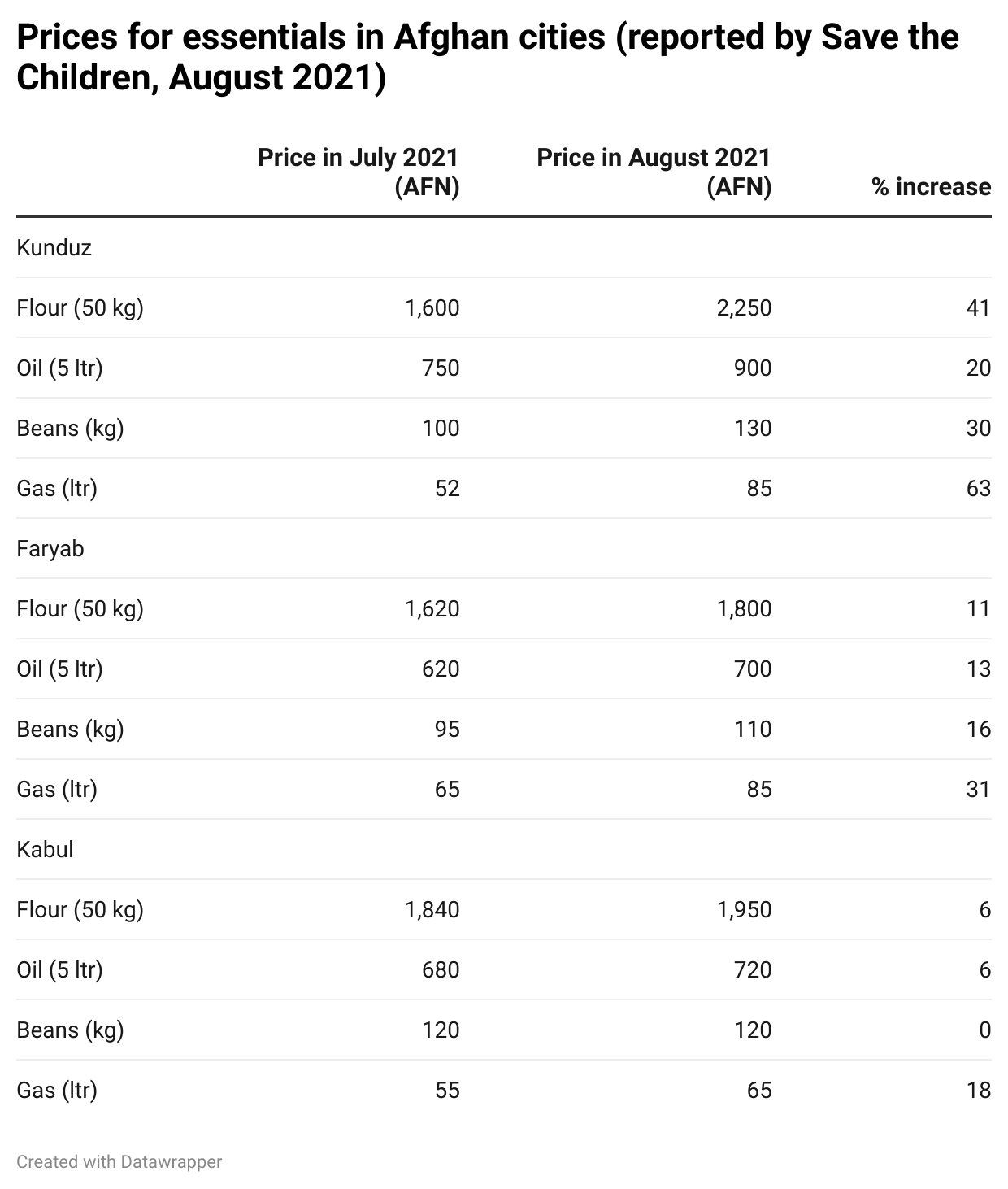

On August 26 the charity Save the Children reported the following figures for price increases from its staff in cities across the country.

As the charity added: “A survey of 630 newly displaced families in Kabul, carried out by Save the Children earlier this month, already found that all of the families had run up debts in order to buy food. Many families have been forced to sell their possessions, cut back on meals or send their children out to work in order to buy food.”

We should not say that we were not warned. These are the signs of a famine to come.

In a situation of acute food shortage, logistics are critical. Famine is normally concentrated in pockets. If food can be transported into the worst-affected areas, the suffering can be mitigated. In Afghanistan that depends on truck transport and truck transport depends on imported petroleum, which has to be paid for.

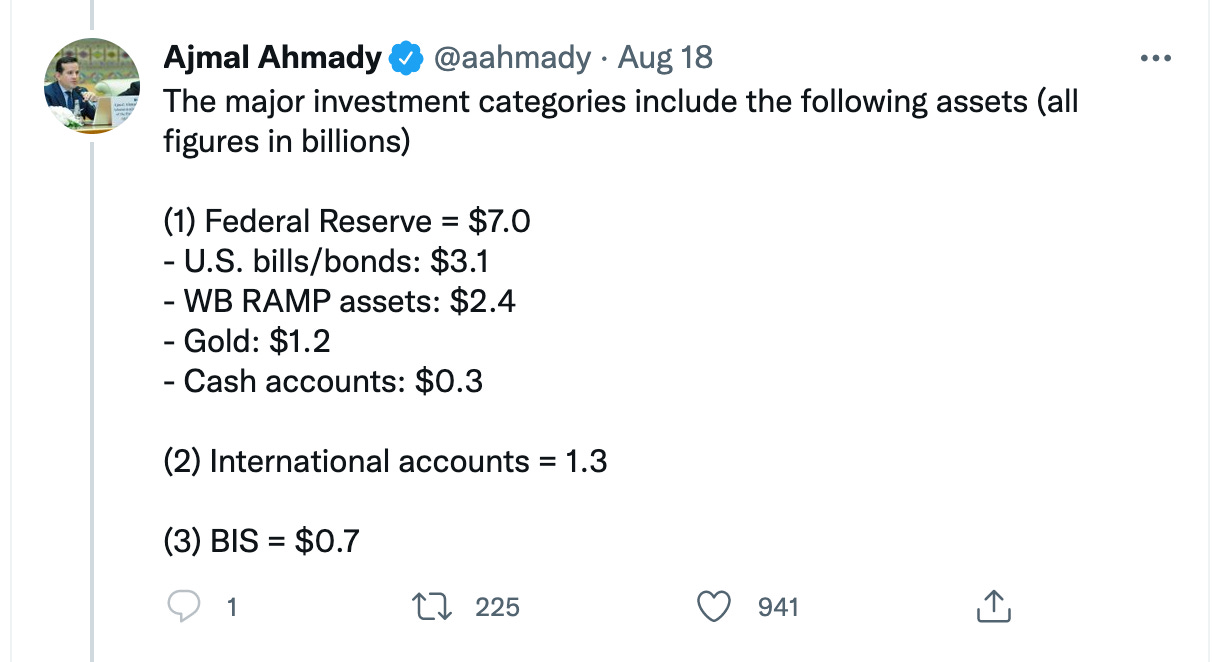

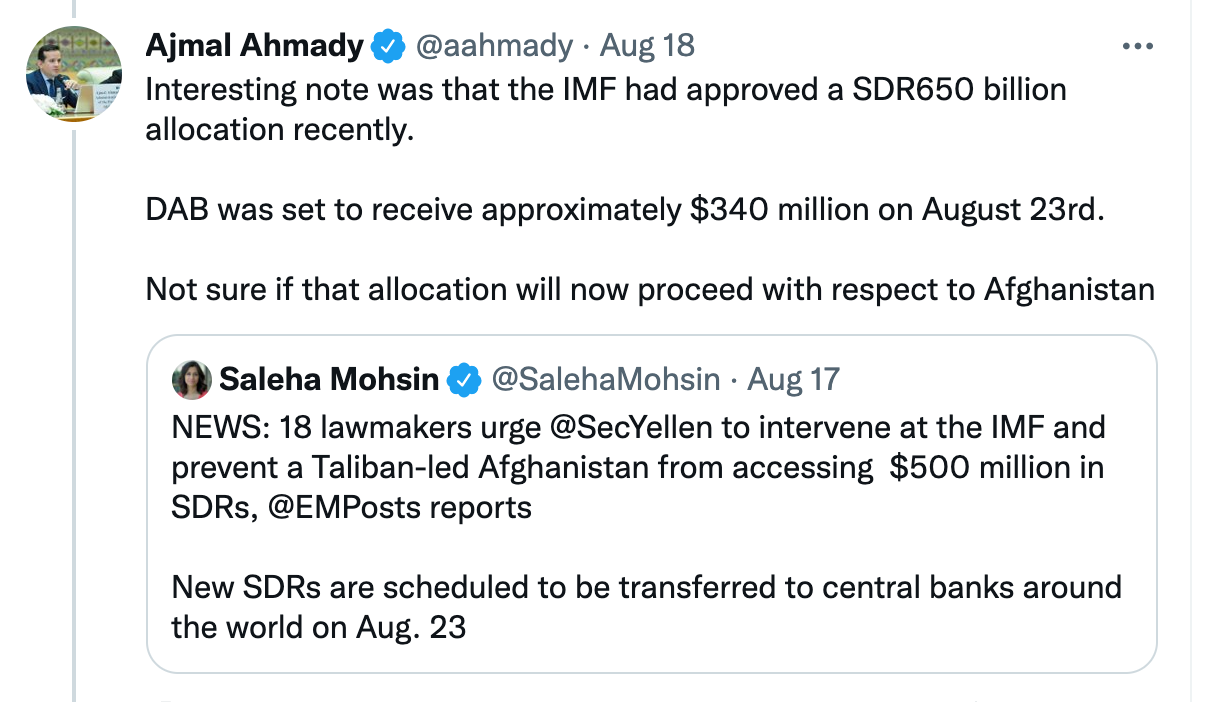

And here is the thing, Afghanistan, notionally, has the funds to tide it over. Its national currency reserve is listed at slightly over $ 9 billion. That is enough to cover its import bill for well over a year. But those reserves are not in Kabul. As departing central banker Ajmal Ahmady tweeted, the Taliban were shocked to discover that the funds were, in fact, disposed of as follows:

As the Taliban seized Kabul, the US imposed a block on all of Afghanistan’s national reserves in the United States. The World Bank and the IMF have both stopped the disbursement of funds, as has the German aid agency, a major donor.

Worryingly, this was accompanied by a political campaign in Washington to deny “funds for the Taliban”.

The Wall Street Journal has followed up with hawkish editorials demanding that none of the IMF’s “funny money” should be made available to Kabul.

The United States is the last country in the world that should, at this moment, be taking the lead in securing Afghanistan’s survival. But someone must. What is needed is a multilateral financing package both to cover the immediate humanitarian crisis and Afghanistan’s acute import needs. The overwhelming majority of this should come in the form of grants. If loans are involved, the funds in the US Federal Reserve need not be released. They can serve as collateral for a funding scheme. But given Afghanistan’s trade position its ability to service international debt is extremely limited.

In light of Afghanistan’s immediate existential crisis, financial flows should not be thought of, first and foremost as a means of leverage. If that removes one more tool of influence from the arsenal of the Western powers, so be it. It is time to accept that we cannot impose our will on the situation and to focus, instead, on rescuing what can be rescued.