Afghanistan, the graveyard of demography

Doing the first Afghanistan report – Chartbook #29 – has rocked my world a little bit. I did not appreciate how complex and ambiguous was the modernization of Afghanistan’s economy and society since 2001. Nor did I appreciate the scale of the 1980s devastation. It is very rare for modern societies with an established pattern of population growth to experience a sudden and prolonged reversal. This points to a disaster of truly enormous proportions.

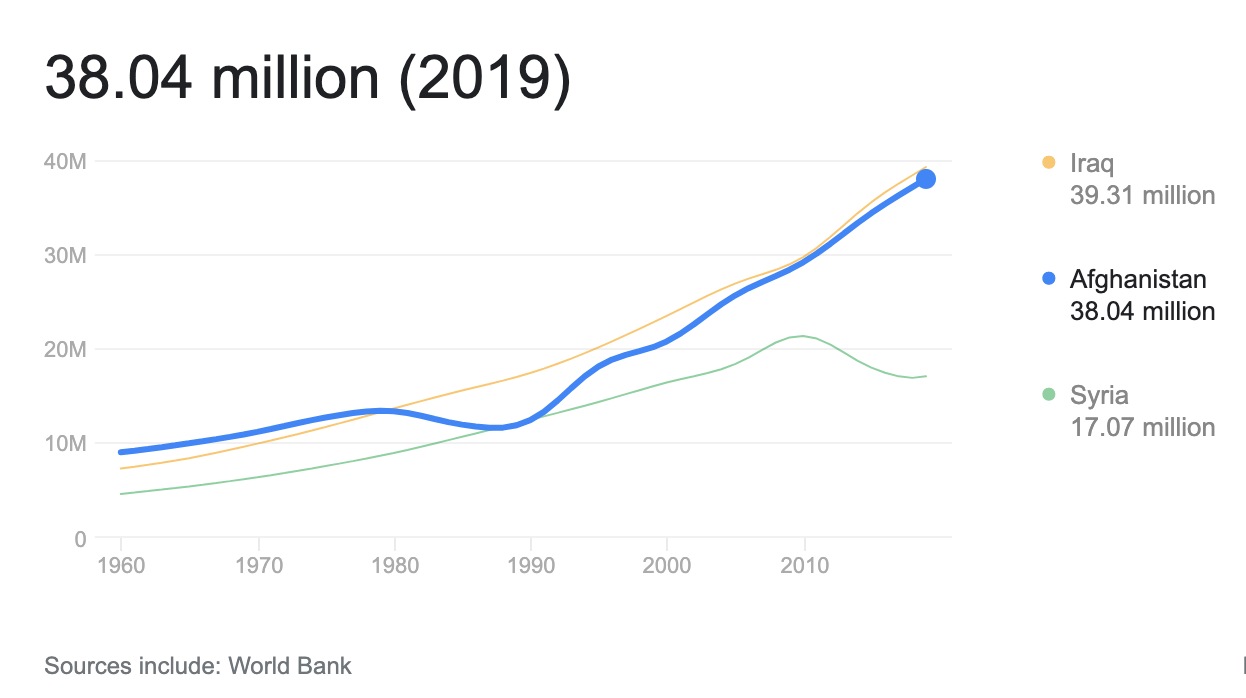

To drive home how anomalous was Afghanistan’s development, compare it to Iraq. Through the late 1970 they had similar populations on similar growth trajectories. They both fought major wars in the 1980s. But whereas the Iran-Iraq war remained largely confined to the battlefield and Saddam’s atrocities were restricted to the Kurdish and Shia areas, in Afghanistan the battle between the Soviet forces, the regime in Kabul and the resistance disrupted civil society and produced a dramatic demographic collapse. What explains that collapse?

Before we attempt to answer that question, a brief note about Chartbook.

******

I enjoy putting Chartbook together. I hope you find it interesting. I know that Chartbook is read by folks in many different circumstances around the world. I am delighted that it goes out free to the majority of readers.

But, assembling all this material does take quite a bit of work. So, if you appreciate the Chartbook content and can afford to chip-in, please consider signing up for one of the paying subscriptions.

There are three options:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

A very big thank you to all those who have given their support to Chartbook. It is much appreciated.

********

Documenting what is happening in a society suffering such violence as dramatic as that in Afghanistan in the 1980s is far from easy. The story of how the demographic data were compiled is itself mind-blowing. Unable to conduct a census in Afghanistan itself, Gallup Pakistan was commissioned by a consortium of international backers to carry out a survey of Afghan families in 318 refugee camps. They reported the losses in their families and their villages. Those data were checked and then the percentage rate of casualties are applied to growth and death rates projected forwards from the census of 1979.

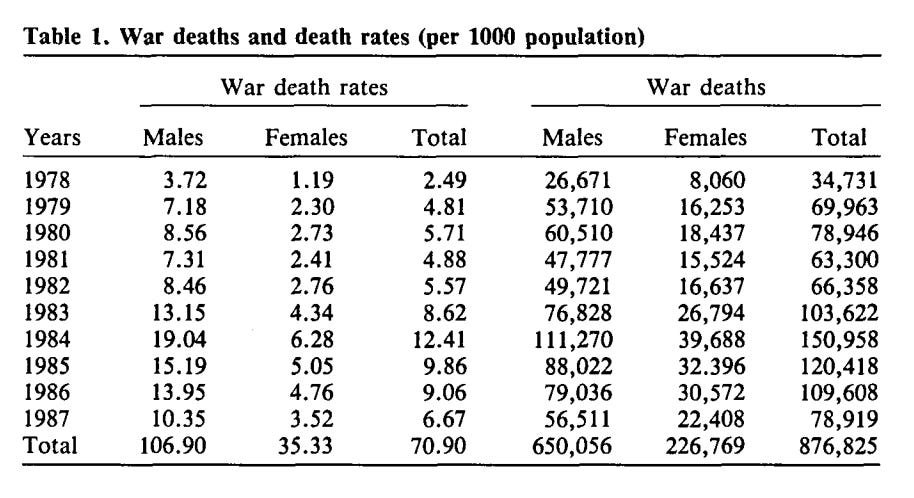

In his widely cited article of 1989 – The Decimation of a People – Marek Sliwinski produced an estimate of total casualties amounting to 1.25 million or 9 percent of the prewar Afghan population. Based on the same refugee camp survey, but using a different population base, M. Siddiq Noorzoy estimated the number of persons killed to be as high as 1.7 million. But all these estimates depend on assumptions about the underlying population impacted by the war. Applying a more sophisticated demographic approach, in 1991 Noor Ahmad Khalidi revisited the estimates, breaking the population down into separate age slices. He arrived at a figure of 876,825 dead.

Source: Khalidi 1991

Any of these numbers signifies an epic shock. To err on the side of caution I have used Khalidi’s estimates in my tables.

Though there is disagreement about the total figures, there is no doubt about the relative balance of casualties. In the provinces closest to the border with the Soviet Union overall casualties may have amounted to a staggering 16 percent of prewar population.. The most heavy toll was taken of men of middle age. Sliwnski estimated that of all men between the age of 31 and 50, 22 percent did not survive the war. Those are rates of mortality typical of combat units, applied to an entire population cohort. It suggests that all Afghan men were effectively treated as combatants.

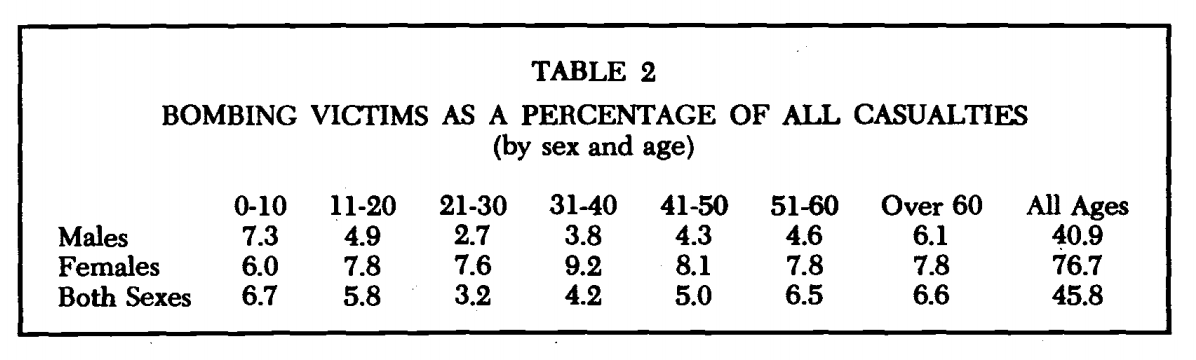

Between 1978 to 1981, the Soviets tried to clear a cordon sanitaire along the Pakistan border by depopulating it through aerial bombings. Amongst civilians, especially women, aerial bombing accounted for the largest number of casualties.

Source: Sliwinski

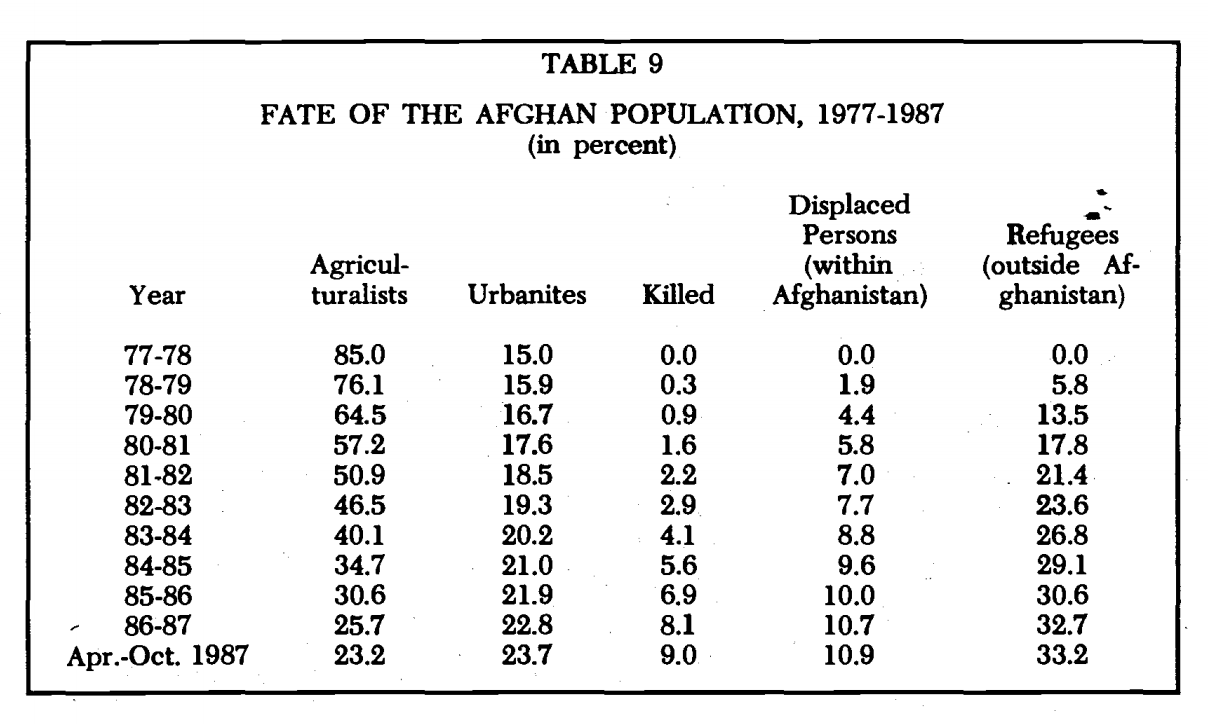

In 1982-4 the focus shifted to “clearing” the northern and central zone around Kabul. Then the focus shifted to control of trunk roads and railways, linking the central area to the Soviet Union. The overall impact was to depopulate the countryside and drive people either into the cities or into refugee camps. Sliwinski quotes officials in Kabul to the effect that “if only 1 million people were left in the country, they would be more than enough to start a new society.” If we combine mass death, displacement and the movement of population within the country, the result is a truly staggering rearrangement of population.

Source: Sliwinski

The share of Afghans engaged as agriculturalist in their home villages fell from 85 percent in prewar Afghanistan to 23.2 percent by 1987. The urban population surged. Nine percent died as a result of the war. All told, at 43 percent, refugees, inside and outside Afghanistan, were the largest group of the population. Less than half the population were in settled rural or urban circumstances. Cambodia under Pol Pot, or Poland under Nazi occupation come to mind as societies which have experienced analogous levels of disruption.

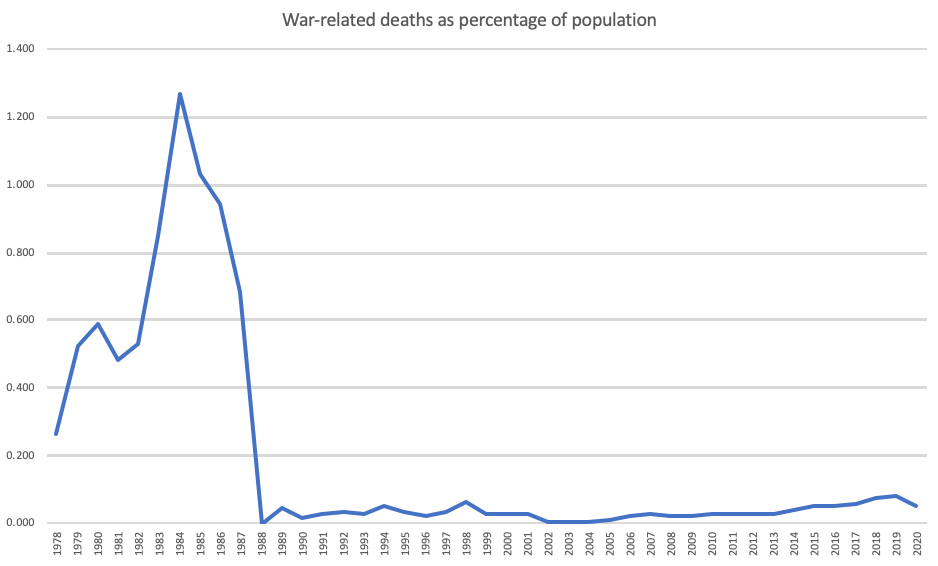

Even using Khalidi’s low estimates, the story is stark. The rate of war-related mortality surges in the 1980s and then falls sharply at the end of the war. Never again has Afghanistan experienced the intensity of destruction experienced in the 1980s.

The general failure to grasp how radical this break is, the sense that Afghanistan since 1978 has experienced a continuity of violence, is most likely explained by the fact that between 1992 and 1996 intense fighting spread to Kabul. A modern city in ruins provided graphic images.

Source: A view of Kabul as documented by Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) during civil war, which shows destruction caused by in-fighting of fundamentalist groups following the fall of the pro-Russian government of Dr. Najibullah in 1992.

If we take the country as a whole, the demographic data suggest that Afghanistan in the 1990s was actually beginning its slow recovery from the horror of the 1980s. The question is how fast.

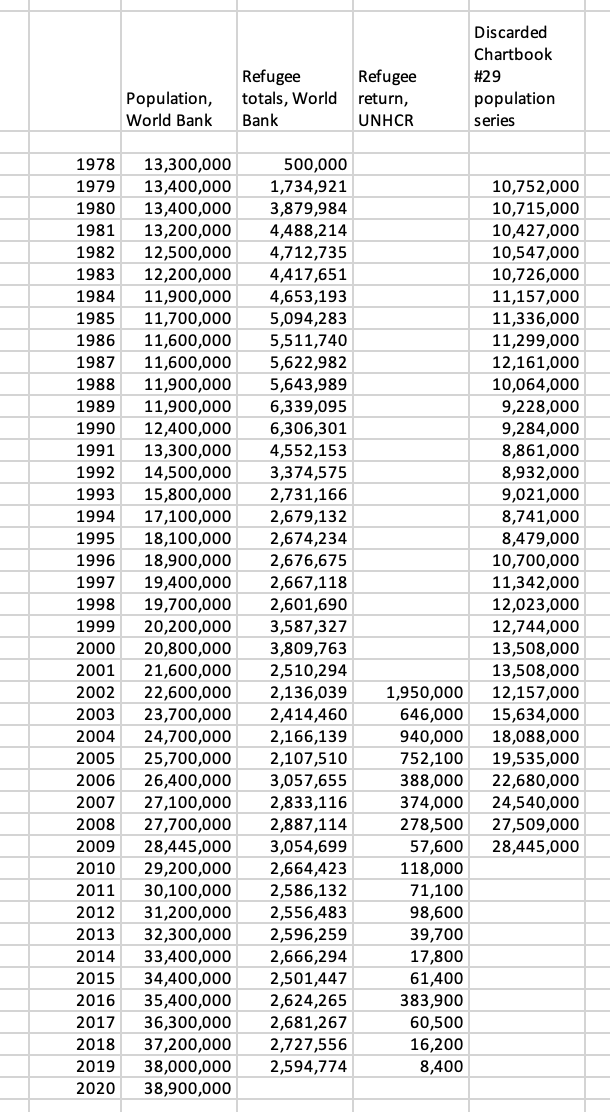

In Chartbook #29 I used a set of figures for population whose origins are frankly a little obscure. They show a very low population in the 1990s and a surging increase after 2001. I chose them because I assumed that they excluded the refugee population. I was looking for a measure not of the Afghan population as a whole, but of the population remaining in Afghanistan. Since what I was after was the percentage of casualties amongst those exposed to the fighting, it seemed like the best series to use. The discrepancy to World Bank population figures was large. The gap I assumed was due to the refugee population. The US authorities counted over 6 million returnees after 2001. That was enough to explain the difference.

But the more I have learned about the difficulty of accounting for the refugee population, the less secure this approach seems. The safest figure to use is simply the population of all Afghans, whether inside or outside the country. I have recalculated the key tables here using the standard World Bank figures and updated those in Chartbook #29 online accordingly. The upshot is that as the intensity of combat declined in the 1990s in most of the country – the air raids stopped – the demographic recovery began. As a result, after 2001 the population doubles rather than tripling.

The refugee numbers are really a minefield. It is generally agreed that in 1990-1991 6.3 million Afghans were living in camps. After that, the overall number decreased. By the late 1990s the UNHCR count had fallen to 2.66 million. But the numbers fluctuate. In 2001 the figure was back up to 3.8 million. So how, if there were 3.8 million refugees in 2001 could over 6 million have voluntarily returned to Afghanistan over the following twenty years? How could there be more returnees than there were people in camps in 2001?

The answer is that the refugee population is not static. People leave the camps to return, are then forced back into the camps from which they then “return” again.

Though the overall trend has been downhill since 2001, there were 2.6 million living in camps in 2000. As the Taliban advance becomes ever more ominous, that number is swelling by the day.

As this excellent MPI report notes, “only in January 2015, at the height of the Syrian crisis, did Afghans finally lose the status that they had held for 30 years as the world’s largest refugee population.” If Afghans again take to mass flight, how will their neighbors – above all Pakistan and Iran – react?

In 2016 the then Pakistani government demanded that all Afghans leave the country, precipitating a forced return of 500,000 people. In light of the ensuing chaos, in 2017 it relented. It is reckoned that 2.8-3 million documented and undocumented people from Afghanistan continue to live in Pakistan. Imran Khan’s government has let it be known that it will accept no more. The proposed solution is to build camps on the model of Iran, not inside Pakistan but along the border to Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, relations between the US and Pakistan – once a designated ally in the region – continue to be strained. Military aid to Pakistan was terminated by Trump. Then, after Pakistan helped to arrange talks with the Taliban, Prime Minister Khan was received at the White House. Talks were held between Pakistani security officials and Jake Sullivan at the end of July 2021. But Biden has yet to make time for a phone call with Prime Minister Khan.

Though the Taliban were a creature of Pakistan’s intelligence agency, in 2014 the Pakistani military struck a heavy blow against TPP, the Pakistani associate of the Taliban. Right now, Islamabad and Washington share an interest in stabilizing Afghanistan. And so does China, which has One Belt One Road projects stretched across the region. In 2020, TPP reformed. Under the influence of AQ-inspired leaders, TPP has widened its appeal to strike against Chinese as well as American assets in the region. There is no outward sign, at least, of cooperation between the US, China and Pakistan. With victory apparently within sight, the Taliban in Afghanistan show no interest in coming to the table. As the FT quoted Moeed Yusuf, Pakistan’s national security adviser: “Everybody’s lost leverage over the Taliban”.

To the North, Tajikistan has announced that it is preparing to receive as many as 100,000 refugees from Afghanistan. It is already pre-positioning supplies. Tajikistan has mobilized 20,000 reservists to secure its border and has asked Moscow, which has troops stationed in the country, to help it in containing any spillover of armed groups.

As Carter Malkasian remarked to the FT: “The most painful moment is yet to come”. Given Afghanistan’s history, let us hope fervently that he is wrong.