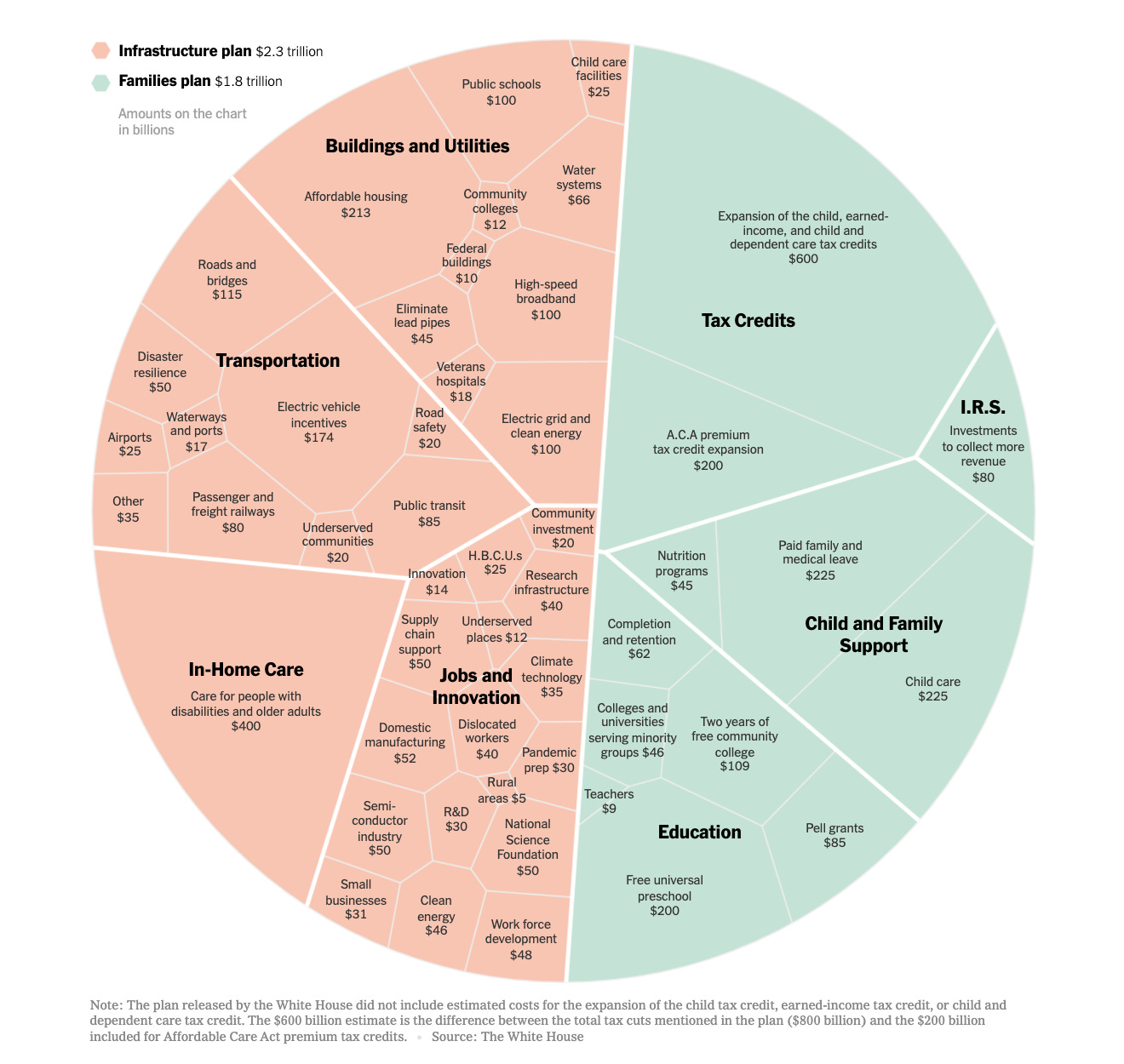

Biden’s Families Plan is the third of his economic packages. Billed at $1.8 trillion over ten years, the Families Plan complements the immediate support provides by the Rescue Plan and the long-term Jobs/infrastructure Plan.

Source: New York Times

The Families Plan concludes the sequence, but the family has been a key preoccupation of all three of Biden’s programs.

The Rescue Plan offered hundreds of billions in support for child care providers and families in the form of family tax credits. It established what amounts to a temporary child benefit system. The Jobs/infrastructure plan provided $400 billion for elder care. As David Dayan summarizes in the American Prospect, the Families Plan adds to that a long-term continuation of child tax benefits, hundreds of billions for child care and Federal backing for paid family and medical leave.

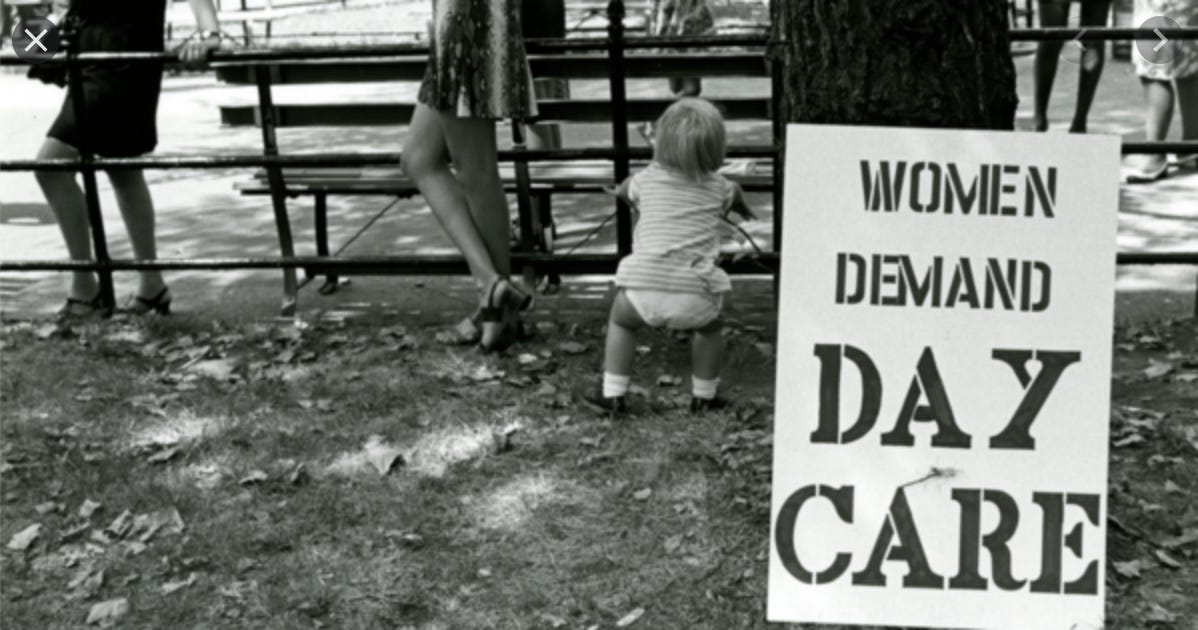

Pushing a progressive agenda for families and young people, the Biden administration takes up a cause whose historic origins can be traced back at least to the 1960s.

The Johnson administration launched Head Start in 1965 to address the acute problem of child poverty – at the time, half of Americans living in poverty were children.

In 1971 Congress passed the Comprehensive Child Development Bill that was intended to create a nation-wide system of federally-funded child care centers, affording women greater opportunity to enter the workforce and both custodial and educational support for children. As Palley and Shdaimah stress in their foundational history – In our hands. The Struggle for US Child Care Policy – with the backing of the AFL-CIO, child care centers were seen as comprehensive support centers for children and their parents, offering basic health care as well as educational services and help with extra-curricular socialization.

As Walter Mondale remarked at the time: “the American people must realize that there is no answer to the unfairness of American life that does not include a massive preschool comprehensive child development program. Anything less than that is an official admission by this country that we don’t care.”

Despite the fact that the Bill was passed with bipartisan support by both the House and the Senate, it was vetoed by Richard Nixon. In the explanation for his veto he warned that public child care would weaken the family and import to the United States the practices of the Soviet Union.

The coincidence of the decisive battles over child care policy in the early 1970s with the “Nixon moment” was anything but accidental. The early 1970s were a turning point.

As Melinda Cooper has shown, in her highly original book Family Values, the breakdown in existing monetary order and the social upheaval of the late 1960s unleashed a challenges to the status quo on multiple fronts at once – in gender politics, sexuality, the politics of race and economic policy. The alliance between neoliberalism and neoconservatism answered in kind, linking a defense of a restored “traditional” family to a reassertion of the market order and an overturning of the New Deal compromise on welfare.

Cooper’s is an American story. But the association of neoliberalism and new social conservatism axing on the family had a powerful resonance also in Thatcher’s Britain.

For Thatcher, famously, there was no such thing as society. The alternative to society, however, was not simply the individual, but the family. As Thatcher herself put it: “Who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families.”

The family is a core institution for all forms of bourgeois order. The family is the place, one might say, where social forces reach critical mass. But, in recent decades, families, and American families in particular, have become an ever more crucial arena of success and failure, of the accumulation of social and cultural capital and social and psychological dysfunction.

This manifests itself in ceaseless debates about individual choice and the pressures and expectation of childhood, young adulthood and parenthood. But, as James Chappel summarizes it in a review of Cooper, all these personal and collective stresses were framed by the new dispensation of economic policy, which saw the nuclear family rather than the state, “as the privileged site of debt, wealth transfer, and care.”

Nothing in the Biden agenda of 2021 puts this basic dispensation in question. What the Biden administration is responding to, is the fact that the specifically American model of family policy – or non-policy – the model that was first framed half a century ago in the culture wars of the 1970s, has reached an impasse.

Whereas the Washington consensus that emerged from the collapse of Bretton Woods in the early 1970s forced convergence on some key issues of economic and financial policy – the abolition of exchange controls, central bank independence, trade liberalization, the protection of intellectual property, a global regime (or non-regime) of banks supervision, to name the key areas – in other fields of policy the pressure of convergence was much less pronounced. One field of divergence was environmental protection and climate policy. Another was family policy.

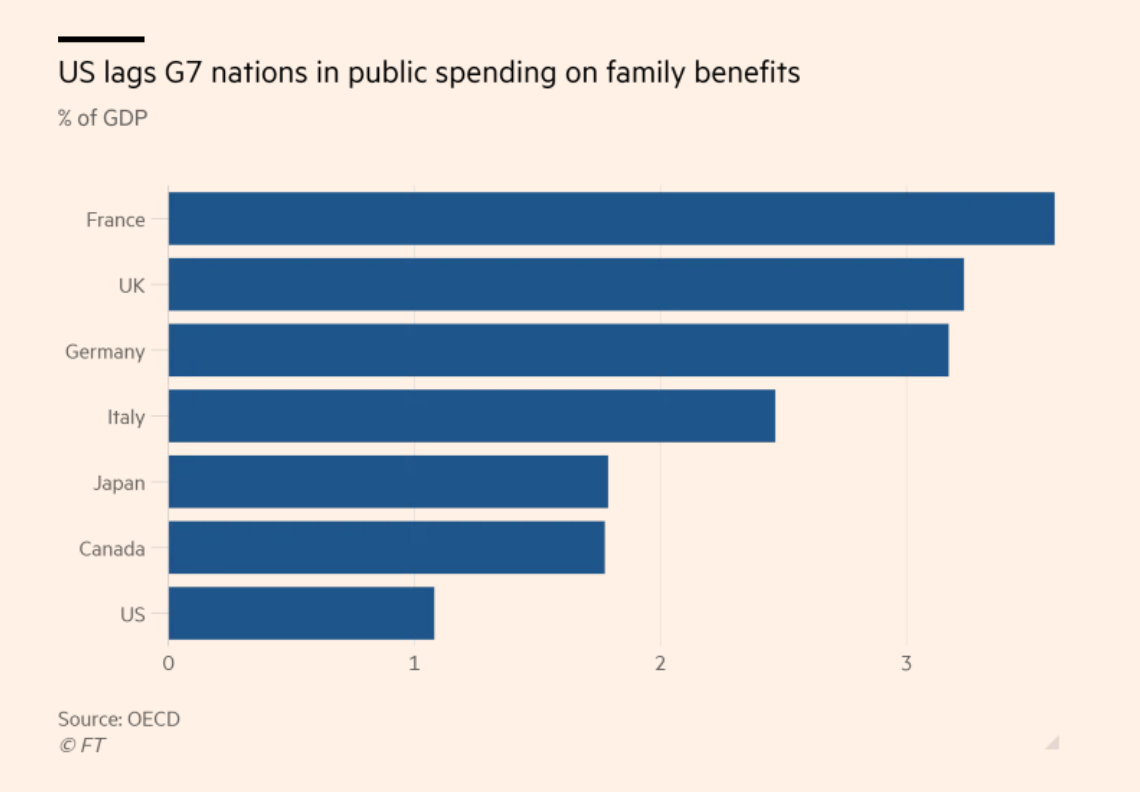

Europe’s welfare states are the outgrowth of state regimes driven by interest group pressures and natalist ambition. They are the opposite of revolutionary. But they do put a considerable amount of public money behind families and care-givers, as core units of reproduction, labour and economic activity.

France since World War II has eagerly promoted natalism. The newly unified Germany has formed a hybrid of Christian Democratic conservatism with the childcare ambitions of the GDR. The UK has an expensive privatized childcare regime, but also spends significantly on child benefits. Though, by no means luxurious, Europe’s child and family support regimes are vastly superior to those of the US.

The distinctive path of the US out of the common crisis of the 1970s was a family policy regime of absolutely minimal state spending. As a result, amongst the advanced economies, it is the most difficult place to raise a family on a median income.

Source: FT

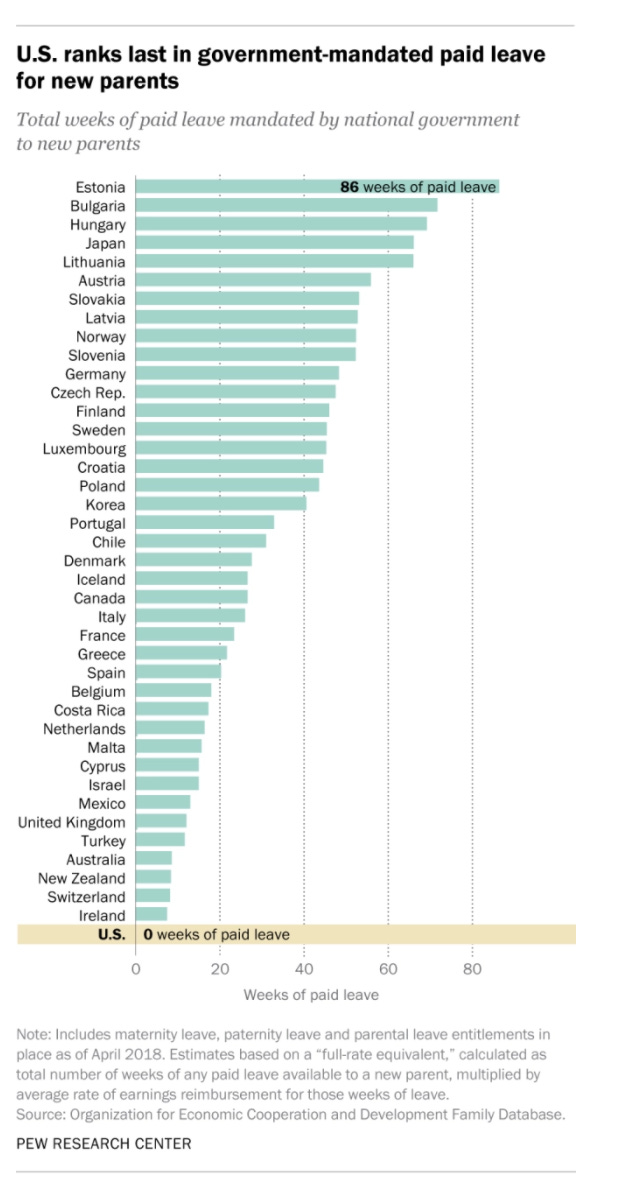

When it comes to basic entitlements in most advanced economies, the United States flouts conventional civilizational standards. No federal laws require paid leave in the U.S. The U.S. is the only wealthy country that does not legally require parental leave. Public childcare provision is grossly inadequate.

Source: Pew

Before the pandemic, only 20 percent of private sector workers in the US had any paid family leave entitlement and only 8 percent of those on low wages.

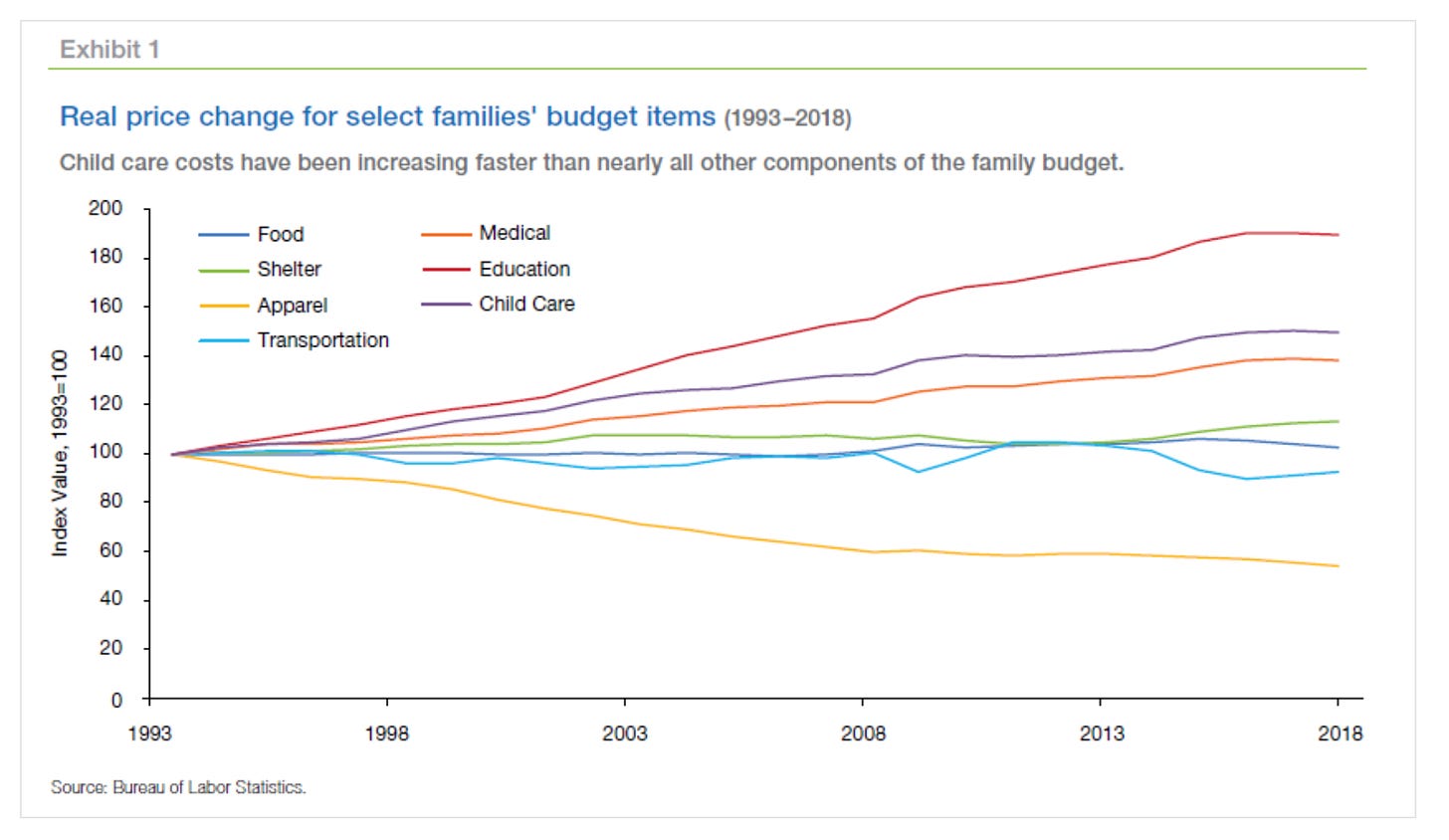

Private childcare in the United States is not just expensive, like education it has risen in price relative to all other expenses of the typical American family.

Source: Freddie Mac

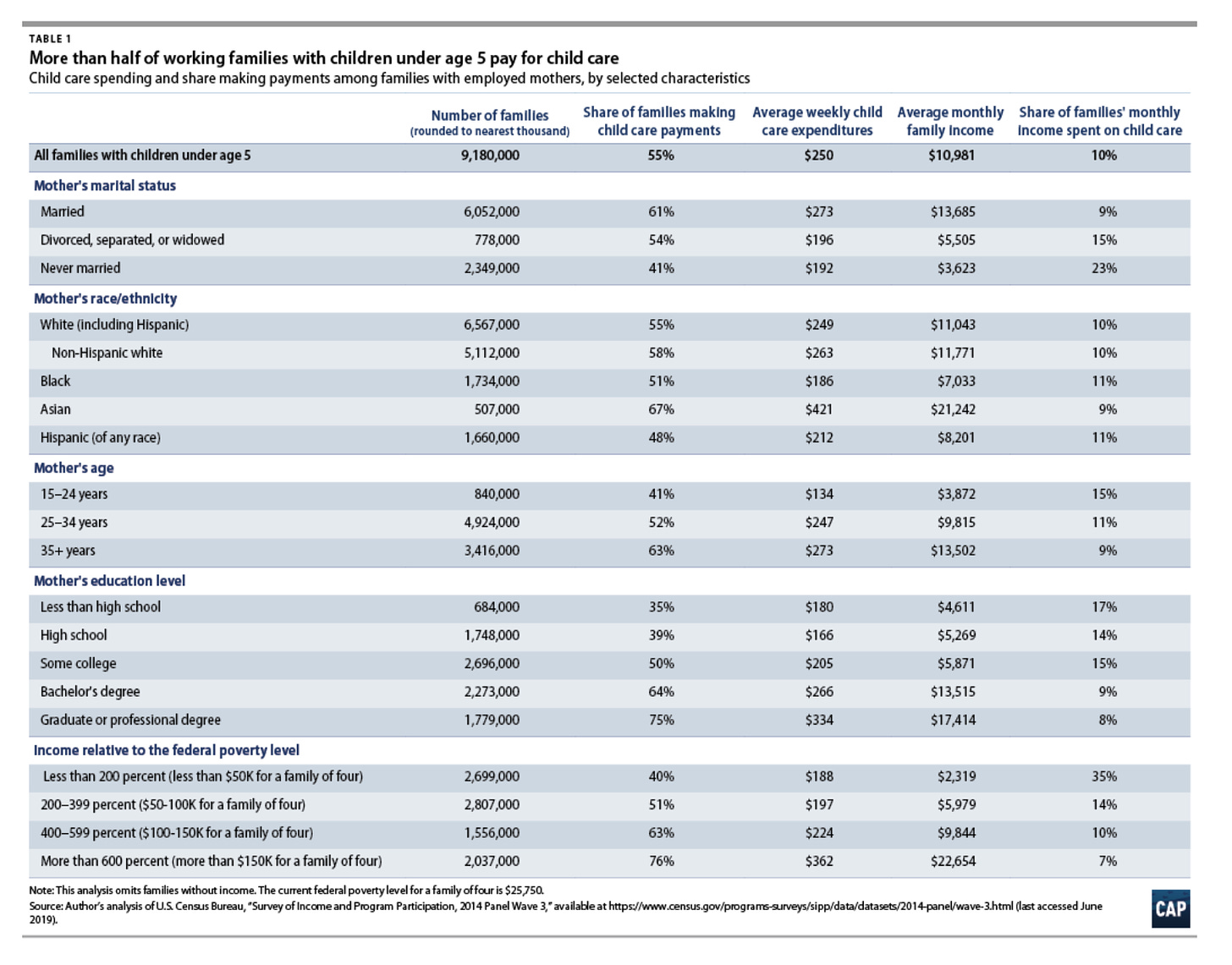

The consequences for American families and children are dramatic. Whereas high income families pour resources into their children’s care and education, lower income and middle-income families struggle. According to census data collected in 2019, in low income families that do afford childcare, it eats up on average 35 percent of their monthly income. Only for the top quarter of American households are child care costs officially classified as “affordable”, i.e. they amount to no more than 7 percent share of income.

Source: Center for American Progress

Increasingly, this threadbare patchwork has been identified as not only socially inequitable but a dead weight on American economic performance. On virtually every assessment, early childhood education yields huge returns.

The choices facing American parents are invidious. With more than one child, unless both parents enjoy high salaries and the prospect of long-term career advancement, the cost-benefit analysis of childcare is unfavorable.

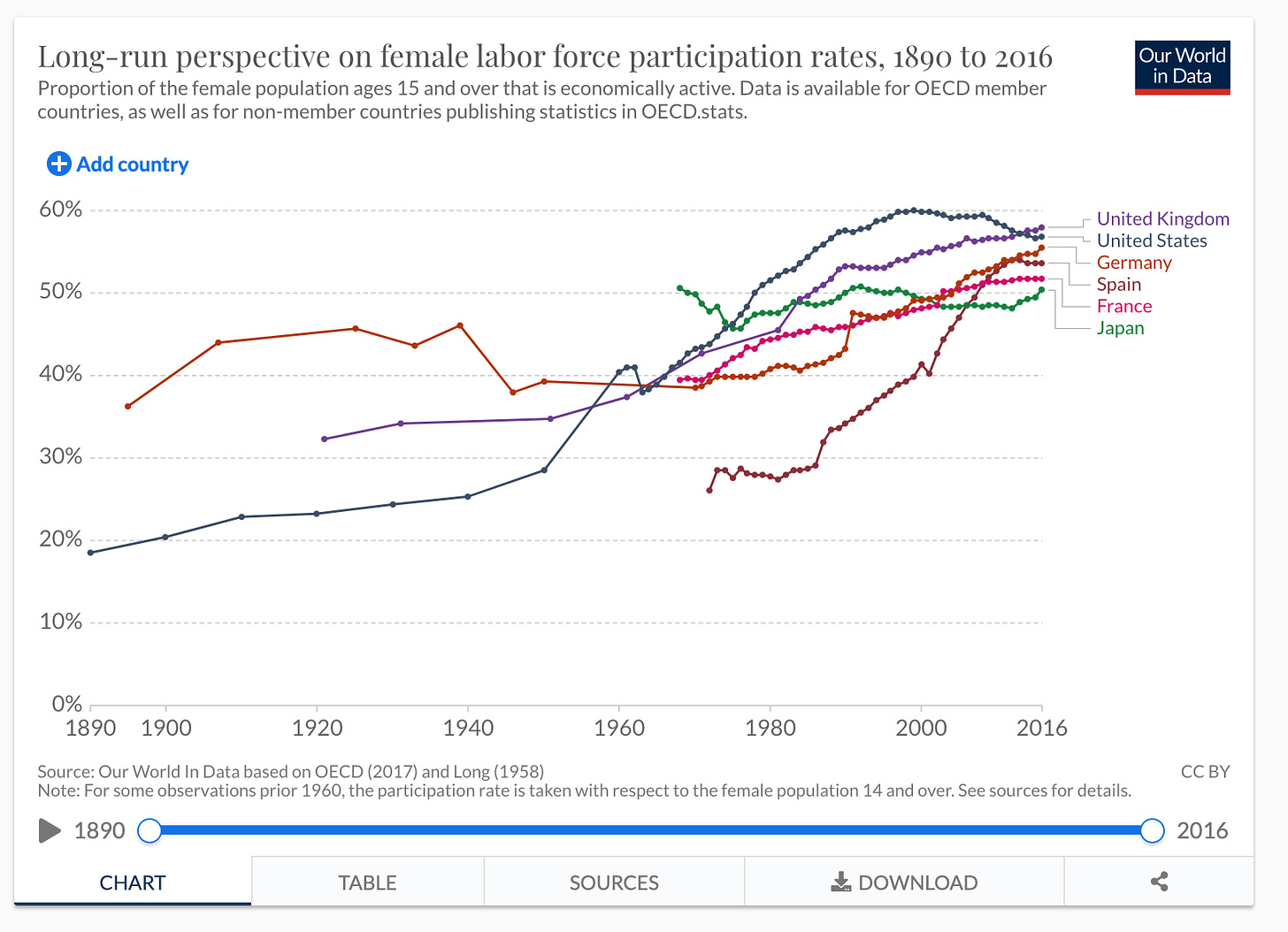

Little wonder, it is argued, that labour force participation by American women, has stagnated whilst other countries have caught up or even overtaken the US.

Source: Our World In Data

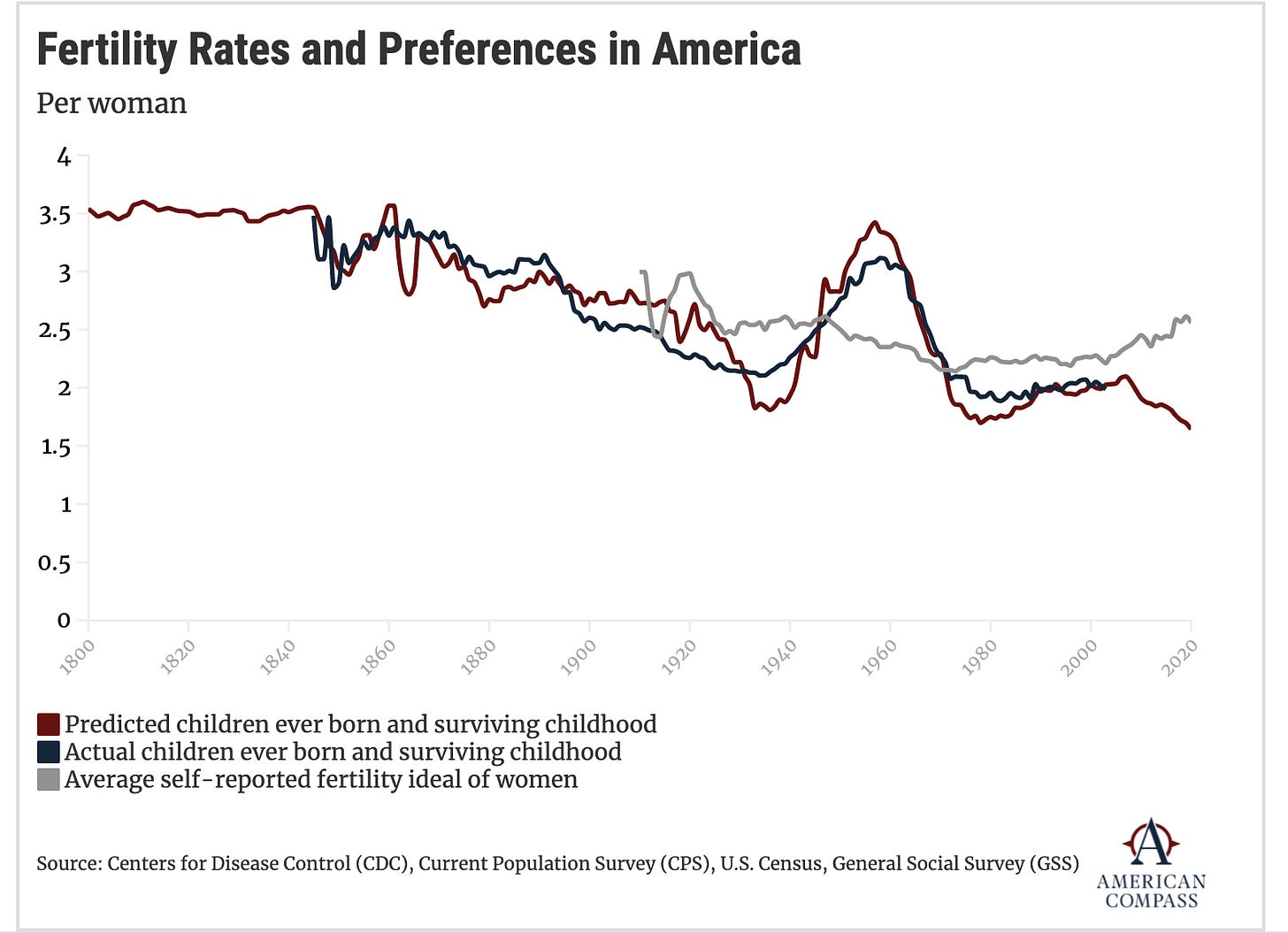

Little wonder also, that from the early 2000s there has been an increasingly large gap between the number of children American women give birth to and the number they would, ideally, like to have.

Source: Stone (2021)

In the current moment, a mounting sense of unease about the fabric of American society blends with a preoccupation with national decline.

In its history to date, economic growth in the US has been driven by population expansion. In 1900 the population of the US stood at 76 million, the population of the UK was 30.5 million and that of France, 38 million. By 2019 the population of the US had exploded to 328 million, whereas that of its European counterparts had merely doubled to 66-67 million. In the half century since 1970 America’s population has grown by 125 million people, as many as the entire population of France and the UK put together.

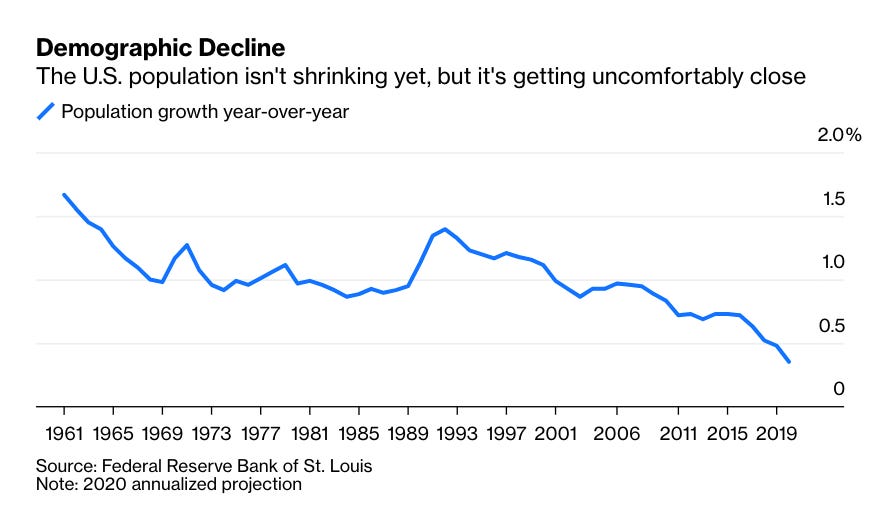

Population expansion drives investment and growth. America’s dynamic demography gave American business a rapidly expanding market. Now, as Noah Smith remarks in a recent Bloomberg column, the US is losing its “population advantage”.

Source: Noah Smith Bloomberg

Both declining immigration and the falling birth rate are driving this slowdown. As childcare costs surge, ceteris paribus, it is hardly surprising that Americans are having less kids.

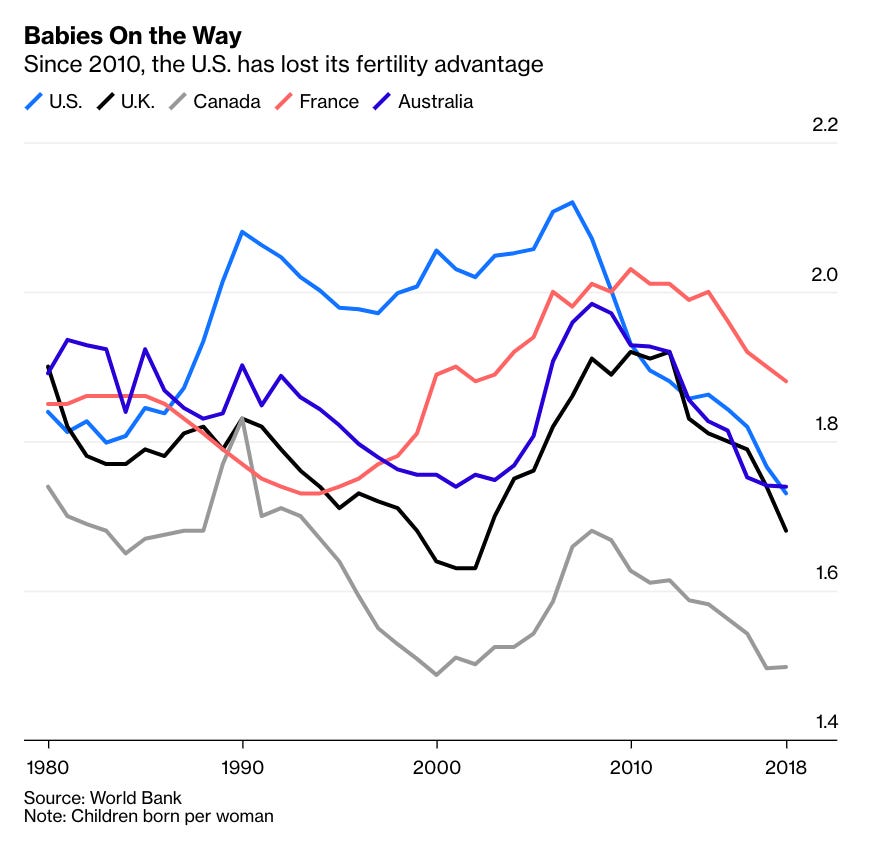

Source: Noah Smith Bloomberg

In the figures for births we see a particularly sharp inflection after 2007. Was the financial crisis one shock too many? Was a critical pain threshold reached? As Noah Smith points out, decline is also driven by job market prospects and the particularly marked decline in the Latino birth rate.

Whatever the immediate cause, since Larry Summers intervention of 2013 on the theme of secular stagnation, demographic concerns have merged with a wider discourse about national slowdown.

Melinda Cooper has addressed the stagnationist nexus of demography and economics in two brilliant essays. As she shows, in 1920s the fear of British Malthusians about overpopulation gave way to an increasing preoccupation with population decline. Keynes was increasingly worried about the possibility of long-term stagnation. It was Alvin Hansen’s theorizing about secular stagnation in his address to the American Economic Association in 1938 that Summers would take up in 2013. In recent times, the first place where the fear of secular stagnation driven by demographic slowdown was widely addressed was in commentary on Japan in the 1990s. In both cases, Cooper argues, a preoccupation with demography provided a convenient way of not talking about social inequality and underconsumption driven by the maldistribution of income.

The Biden administration is clearly preoccupied with issues of national competition. It is possible that concern about demographic decline and secular stagnation are on its mind. But if this is the case, the administration is keeping it quiet. As far as I am able to tell, Biden’s proposals have so far avoided any mention of demography. The focus is squarely on the 1960s and 1970s agenda of social uplift, inequality and child poverty.

Like the American Jobs Plan, the measures proposed in the American Families Plan will please many campaigners. But, as with the American Jobs Plan, the question is whether the Families Plan is anywhere near large enough.

If one adds up the entire Families Plan, the elder care element in the Jobs Plan and the family support element of the Rescue Plan, we arrive at a figure in the vicinity of $2.5 trillion. Spread over 10 years that makes $250 bn per annum. On a generous estimate that is enough to raise America’s public spending on families by a little over 1 percent of GDP. Added to currently spending on families that would put the United States roughly on a par with Italy, a country which in Europe is widely regarded as having a failed regime of family policy.

The Biden plan does not provide any paid leave for those dealing with short-term illness of their children. For that Biden is asking for Congress to pass a separate Healthy Families Act. And with 12 weeks paid family leave, the United States will remain close to the bottom of the league tables. One can only imagine how those will look ten years from now when the Biden Plan, if passed, would finally come into full effect.

And then, finally, there is the big catch. As with the American Jobs Plan, the numbers in the Families Plan are the administration’s first ask. They are matched by payfors, tax increases, which are themselves hugely contentious. Whether either the tax or spending plans can find a majority in Congress remains to be seen. In family policy, as in climate policy, the Biden administration wants to patch the ailments of American society and bring it into line with other advanced economies, but it remains hobbled in its scope for truly bold action. As Jeff Stein remarked in the Washington Post, the Families Plan reflects both the ambition and the limits of the Biden Presidency.