When I arrived at Yale back in 2009 I was deeply impressed/shocked by the degree to which the assumption of “forever war” had become entrenched there. I sat in on courses at the law school where the only interest was in jus in bello. Questions of jus ad bellum were cast aside as utopian irrelevance. Having been raised in West Germany and absorbed the end of the Cold War against that background, it was a considerable shock. My reaction was to put together an undergraduate course on War in Germany from the Thirty Years War to the present, which was an effort to historicize the arc of modern militarism and to insist on its historicity. This term I’m reviving the course at Columbia, under the sign of an American administration which is far more explicit in its commitment to the timeless importance of great power competition.

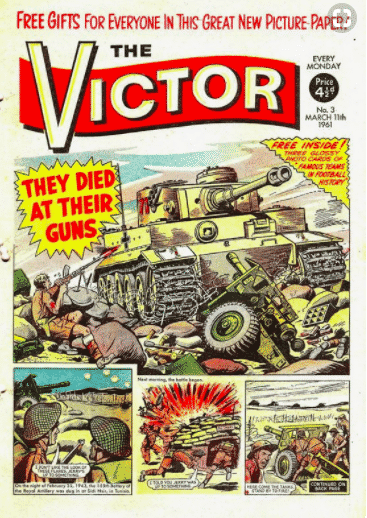

It is also a rather personal project in another sense. My early childhood was entirely formed by the military/World War II play culture of 1970s Britain. Victor and Commando comics, Airfix soldiers and war gaming were my obsessions. From an early stage I was drawn, for reasons I cannot fully explain, towards the German side.

The shock of actually moving to Germany in 1973, to Heidelberg, an academic, left-wing university town deep in the heart of the Federal Republic was considerable. I turned out to have not one (the ordinary one) but two imaginaries subject to a more or less explicit taboo. It was not that there was no culture of militaria in West Germany, but it belonged in the shadows rather than the central position it occupied in 1970s Britain. Children were not particularly welcome where the memories of the Wehrmacht lurked.

Much of my formation from that point forward was shaped by that tension.

It will be my weekly preoccupation for the next three and a half months. I’d be delighted to have people’s reactions, comments and suggestions on the syllabus and powerpoint, which I will post on a semi-regular basis.

The powerpoint for Lecture 1 is here: WinG2018 Lecture 1.

The syllabus is as follows.

War in Germany 1618-2018

Spring 2018

For much of modern history Germany was Europe’s battlefield. Its soldiers wrote themselves into the annals of military history. But it was also a place where war was discussed, conceptualized and criticized with unparalleled vigor. Nowhere did the extreme violence of the seventeenth century and the early twentieth century leave a deeper mark than on Germany. Today, as we enter the twenty-first century, Germany is the nation that has perhaps come closest to drawing a final, concluding line under its military history. This course will chart the rise and fall of modern militarism in Germany. For those interested in military history per se, this course will not hold back from discussing battles, soldiers and weapons. But it will also offer an introduction to German history more generally. Through the German example we will address questions that haunted modern European history and continue to haunt America today. How is state violence justified? How can it be regulated and controlled? What is its future? How did Germany become the state that has come closest to drawing a final, concluding line under its military history?

Lecture 1 Jan 17 War in German History

Lecture 2 Jan 22 The Thirty Years War as civil war, religious war and apocalypse

Lecture 3 Jan 24 Westphalia, the European state system and the rise of Prussia

Lecture 4 Jan 29 Frederick the Great and Prussian militarism

Lecture 5 Jan 31 Perpetual war or perpetual peace? Cabinet wars and their enlightenment critics

Section 1: Prussia’s precarious rise: Thirty Years War to Frederick the Great

Lecture 6 Feb 5 Napoleon, Prussia and the destruction of the ancien regime

Lecture 7 Feb 7 1813: people’s war and national liberation

Section 2: Absolutist war, enlightenment criticism and Kant’s vision of Perpetual Peace

Lecture 8 Feb 12 Clausewitz a philosopher of war?

Lecture 9 Feb 14 The Congress of Vienna and the threat of revolutionary war

Section 3: Napoleon, Clausewitz and Hegel – war as historic shock.

Lecture 10 Feb 19 Prussia, Bismarck and reunification

Lecture 11 Feb 21 Moltke and the invention of the modern General Staff

Section 4: Bismarck, Moltke and the problem of German unification

Lecture 12 Feb 26 Imperial Germany in an age of global militarism

Lecture 13 Feb 28 1914

Section 5 Debating the July crisis of 1914

Lecture 14 Mar 5 “Blood mill”: Towards attrition

Lecture 15 Mar 7 Midterm

Spring Break No Section

Lecture 16 Mar 19 1917-1918: Germany’s attempt to win World War I

Lecture 17 Mar 21 From war to civil war? Making peace in Germany

Section 6 The storm of steel: war, revolution and the front generation

Lecture 18 Mar 26 German soldiers and the making of Hitler’s dictatorship

Lecture 19 Mar 28 Blitzkrieg: a new model for twentieth-century war?

Section 7 Myth of the Blitzkrieg

Lecture 20 Apr 2 Narvik, the Atlantic, Tobruk, Ostfront: Hitler’s world war

Lecture 21 Apr 4 Racial war

Section 8 Race war

Lecture 22 Apr 9 Defeat

Lecture 23 Apr 11 Justice at Nuremberg

Section 9 Nuremberg: Judging Hitler’s War.

Lecture 24 Apr 16 Looking back: Legacies of German militarism

Lecture 25 Apr 18 The question of rearmament

Section 10 Coming to terms with the past: cold war memory politics

Lecture 26 Apr 23 Under the Shadow of destruction Cold War Germany

Lecture 27 Apr 25 Post-military security policy – a new German model?

Section 11 From Cold War to post-military society?

Lecture 28 Apr 30 Final

Weekly sections:

Section 1: Frederick the Great and the Rise of Prussia

Questions: Why was the impact of the Thirty Years War on Prussia so devastating? From sandpit to superpower – how do you account for the rise of Prussia? How enlightened was Frederick the Great? Should Frederick the Great be a German national hero?

Section 2: Absolutist war and its critics: Kant and the project of Perpetual Peace

Questions: What made absolutist war so controversial? What was the logic of Kant’s project of perpetual peace? Was Kant’s project realistic?

Section 3: Napoleon, Clausewitz and Hegel: War as historic shock

Questions: How could Napoleon crush Prussia in 1806? Why is Clausewitz, a Prussian patriotic rebel against Napoleon, still required reading for American soldiers today?

Section 4 Bismarck, Moltke and the Wars of Unification

How did Bismarck and Moltke enable Prussia to escape from the impasse of the 1848 revolution? What risks did they run in the wars of unification? How did they contain the risks of revolution exposed by the Franco-Prussian war?

Section 5 Debating the July crisis of 1914

Questions: Was Germany principally responsible for the drive to war in 1914? How important was “military culture”? Was the Schlieffen plan of August 1914 a “Clausewitzian” mirage or a reflection of geostrategic necessity?

Section 6 Storms of Steel: War, revolution and the Front generation

Questions: Revulsion at the horror of war and the trench warfare of World War I in particular is natural. How did certain German intellectuals and politicians form an affirmative vision of war? How did they see it reshaping society? What conclusions did they draw?

Section 7 Myth of the Blitzkrieg

Questions: The victories of Hitler’s Wehrmacht between 1939 and 1941 were more stunning than anything since Napoleon. The term Blitzkrieg is commonly used to describe this revolution in warfare. What substance, if any, lies behind this term? Was it a formula for success or ultimate defeat?

Section 8 Racial War and its legacy

Questions: Hitler’s war was a racial war. How do we account for the complicity of the Wehrmacht in acts of racial war, including participation in the Holocaust? Was it the result of ideological motivation? Was it a matter of peer pressure or the context of particular campaigns? Were there legacies of German colonialism?

Section 9 Judgement at Nuremberg

Questions: Germany’s army committed extraordinary crimes between 1939 and 1945. How were they to be judged? Who would sit in judgment? How does one judge responsibility in military command chains? Beyond judging war crimes can war itself be criminalized? When should soldiers disobey orders? Were the victors wrong to pronounce judgment at Nuremberg?

Section 10 Coming to Terms with the Past: Cold War Memory Politics

Questions: Germany prides itself on having its Vergangenheitsbewältigung, coming to terms with the past. But how was that work done? When was it done and by whom? How were the politics of memory shaped by the Cold War? And which history did the Germans come to terms with, their history as perpetrators or their history as victims?

Section 11 After war: Post military strategy

Questions: German rearmament in the 1950s was controversial. The effort to win the Cold War in the 1980s with a further round of rearmament split German society again. How did this legacy shape how Germany took advantage of the end of the Cold War? How did Germany face the new dilemmas of international security and intervention? Will its post-military security strategy be viable given the rebirth of geopolitics. Is the richest democracy in Europe a model global citizen or a free-rider?