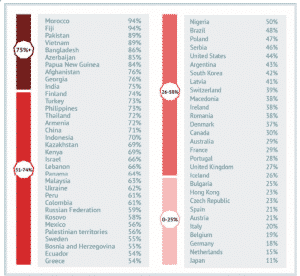

In 2014 on anniversary of WWI gallup conducted a poll on whether people would be willing to fight if their country was involved in an armed conflict. They repeated it in 2015. The results, on the face of it, are impressive for two reasons: the range of difference between countries (94 % Morocco v. 11 % Japan) and the very low numbers in many European countries (15 % Netherlands, 18 % Germany).

The European numbers are particularly impressive both in light of their deep military histories and the “security threats” that are being discussed after Ukraine and Trump’s ambiguous remarks about NATO.

When I posted the data a few days ago, the reaction was considerable. Some folks were skeptical. Others were scornful. Many pointed out that the German public’s lack of interest in fighting was hardly surprising. Some wise historian colleagues suggested that these attitudes were probably no different to those in earlier periods, but that in the event of an actual conflict people change their minds quickly. Ukraine might be taken as a case in point, where a conflict was ongoing in 2014 and where 62 percent indicated their willingness to fight. When the emergency began in 2014, Ukraine’s military was scrambled together on a volunteer basis.

All of these are valid points, but they seem to me to be ways of avoiding the force of the data. In large parts of the world, particularly in Europe, surprisingly few people say yes to this hypothetical question. Allowing for an ordinary measure of cowardice etc. one might expect the reverse. People would feel free to flaunt their patriotism faced only with the hypothetical. Instead, we seem to be presuming that they would do the oppose: say that they would not fight and then reluctantly agree to do so. Before we seek to relativize the remarkable numbers, we ought surely to take them seriously. That anything like this picture is even approximately correct is historically remarkable. And whether or not these attitudes might change in a crisis, they provide a powerful check on the possibilities of security policy under non-crisis conditions. They may also say something broader about the nature of politics or post-politics at our current moment.

Is our current situation historically novel? I think so. The suggestion that at other points in history, earlier in the 20th century one might have obtained similar results is untestable, but I find it implausible. The astonishing thing about Europe in 1914 surely is how large the numbers were that were not just ready but eager to fight. Young men volunteered on a huge scale. We know, of course, that the idea of a huge wave of enthusiasm, the so-called “spirit of 1914” was a myth and that conformist pressure was rife. But it was not entirely a myth. The fact that there was pressure to conform is indicative in its own right. Certainly, it was a world different from the one in which martial patriotism is a truly minoritarian phenomenon.

So, if I am arguing for a break, when do I think it occurred? The idea that Europe’s “postwar” history since 1945 is in fact a postwar history is clearly fanciful. France and Britain have been relentless war-fighters since 1945. Wars of decolonization shaped “postwar” Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands. Clearly fighting a war and having a population that is enthusiastically in favor of doing so are two different things. Was the conditions of French and British activism precisely the fact that they had distinct professional militaries willing and able to fight regardless of wider societal attitudes.

But West Germany in the coldwar is hardly a “postwar” society either. Conscription was general. There was by historical standards very considerable military spending. There was the omnipresent threat of annihilation.

But something did change. By the mid 1990s in less than a third of any cohort of young men in Germany were doing conscript service as opposed to civilian alternatives and from there the number dwindled. Military service became a political lifestyle choice.

How and why did this happen? My guess is that the answer is not the Cold War. My hypothesis would be that the change began in the 1970s. Crudely, one can imagine two different narratives:

The most obvious one is to see it as a reflection of the counterculture of the 1960s, fear and hostility towards nuclear war after the Cuban missile crisis, disillusionment with Vietnam. In short, the anti-militarist, anti-imperialist left won. In places like the US where a new brand of militarism clearly revived in the 1980s, it did so as part of the divisive culture wars, with the civil-military, left-right divide growing very deep. It would be another facet of the Age of Fracture a la Tom Ricks.

An alternative narrative would see the end of national-militarism not so much as a victory of the “cultural left”, but as a correlate of the rise of individualism and consumerism in a “neoliberal age”. The end of conscription in the US in the 1970s coincides with the disintegration of other collective institutions of the age of total war and the “great compression”. Europe would be following the US path belatedly.

One could derive something like this from a sociology of civil-military relations a la Sam Huntington. But something like it also seems to sit behind Frederic Jameson’s appeal to the idea of a universal army in his An American Utopia of (2014). Jameson’s is a very complex intervention indeed and not one I really feel ready to get fully to grips with here.

https://www.versobooks.com/books/2118-an-american-utopia

https://www.versobooks.com/books/2118-an-american-utopia

But, as a conversation starter, take this passage: “As for the draft, it is preeminently symbolic that Nixon ended the draft in order to put an end to popular, and in particular student, resistance to the war in Vietnam (Johnson had already modified the draft with hosts of class and racial exemptions in order to limit its political impact). More recently, during the Iraq war or what we may call the Rumsfeld period, this professional army has been further privatized—and I insist on the relevance of this word for the way it underscores the relationship with the variety of other economic or free-market privatizations all over the world inaugurated by the Reagan-Thatcher regimes. Rumsfeld further privatized this already specialized and salaried private army by outsourcing many of its functions to private corporations of the Blackwater type, and by introducing complex advanced technology in order to render other portions of the military workforce redundant—that is, by downsizing them via mechanization (a process Marx described in Capital). This very significant moment in the history of the modern army had a political purpose above and beyond its adaptation of current late-capitalist business practices: that purpose was to remove this small professionalized group possessing Weber’s proverbial monopoly of violence (currently only .05 percent of the population) from any possibility of mass democratic action and, further, to assimilate it to the structure of the police force, which it seems now to have become on a global scale.

So the first step in my utopian proposal is, so to speak, the renationalization of the army along the lines of any number of other socialist candidates for nationalization (some of which I mentioned above), by reintroducing the draft to transform the present armed forces back into that popular mass force ”

Excerpt From: Fredric Jameson. “An American Utopia.” iBooks.

Of course it is a stretch from a Gallup opinion poll about the willingness to fight, to this kind of structural account of the end of collective institutions offered in Jameson’s discussion of an AMERICAN Utopia. Saying you are willing to fight is not the same thing as approving of the military in general. The universal popular army-welfare state that Jameson has in mind is something else again. Furthermore, the most remarkable numbers are not for the US but on the European side and there are plenty of specifically European and German reasons for those. Can anyone recommend an account of the end of popular militarism in Europe that might bring together these elements, something other than Sheehan’s Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?

German debates about postheroic society may be useful. This piece is interesting W/t Paul Simon

http://www.deutschlandradiokultur.de/postheroismus-wenn-helden-nicht-mehr-noetig-sind.976.de.html?dram%3Aarticle_id=299526