In the course of writing Crashed I was so mystified by the illogic of German policy that I felt I should try to write a book about Germany since reunification in 1989. Last summer I even started work on it.

I wanted to get deeper into what Hans Knundani in the Paradox of German Power has aptly described as Germany’s “semi-hegemonic” role.

In a recent piece in the Economist Jeremy Cliffe put it well:

Why, then, is Germany less mighty than it looks? First, its size can be a weakness … too small to dominate Europe (proportionally it is about as big in population terms as California in America) but big enough that others feel daunted and seek to contain it … Second, Germany’s establishment is different. America has a powerful executive, Britain has a high degree of centralisation and France has both, but in Germany power is diffuse and plural. Opinion is more diverse than the notion of a monolithic German interest and outlook allows … So multilayered and multifaceted are German politics and public life that the country can be in fact frustratingly introverted. Even at the peak of her powers, Mrs Merkel was more a crisis manager than a visionary leader.”

In Crashed I had already begun to map much of this terrain. And in the wake of that book, the German project seemed like a “safe” place to go. Amidst the exhaustion, taking stock and returning to Germany seemed deeply attractive.

Since then, as the after-effects of Crashed have worn off, my need for that kind of reassurance has receded. So I’m focusing my attention on another project to do with climate and energy. I’ll address my German questions not in book form but cumulatively, in essays, reviews and blogs.

Wherever I go, I end up coming back to it anyway.

I

In June, which we spent in Italy, I did two pieces with German themes. The first piece was for Social Europe on Europe’s coal problem, which is really a Polish-German problem.

The trigger for the piece was the dismaying conclusion of Germany’s “Coal commission”, which advised Berlin earlier this year that Germany should not exit brown coal-fired electricity generation until 2038.

Once again, a highly sophisticated German political compromise resulted in an outcome that fails to meet the EU’s climate policy targets, let alone the urgency of the climate emergency.

In the second much longer piece for the LRB I had a swing at analyzing the transformation of the German political scene in recent decades.

The LRB piece was triggered by a request to review Oliver Nachtwey’s Germany’s Hidden Crisis, which appeared in German with Suhrkamp in 2016.

It is to Verso’s great credit that they translated Nachtwey’s book and it was a pleasure being in conversation with Oliver recently when he visited New York, but I felt that the Anglophone audience needed more context.

II

Nachtwey’s book is a product of wide-ranging debates on the German left about their country’s politico-economic transformation since the 1970s. That debate is not merely an intellectual struggle. It is a practical political argument that resulted in the division of progressive politics in Germany, monopolized in the postwar period by the SPD, first with the formation of the Greens in the early 1980s, then in the early 2000s with the splitting off of the left-wing of the SPD as DieLinke in the arguments over the Agenda 2010. Those splits have now been mirrored on the right-wing by the formation of the AfD as a real challenger to the CDU.

Played out both at the national and the federal level this centrifugal political dynamic accounts for much of the multilayered and multifaceted complexity highlighted by Cliffe.

It would be interesting to compare the three moments of “radical centerism” that produced those divisive shocks to the German political system:

in the 1980s, Helmut Schmidt’s adherence to the NATO “Doppelbeschluss” (twin track decision) for the deployment of medium-range nuclear missiles;

in the early 2000s, the Red-Green government’s decision belatedly to adopt the North Atlantic neoliberal agenda of the late 1990s;

in 2015, Merkel’s open borders decision during the refugee crisis of 2015 (preceded by her compromising Eurozone diplomacy that triggered the formation of the AfD in 2013).

There is a rich history to be written of each of those moments. Specifically with regard to Agenda 2010 and 2003 I barely scratched the surface in the LRB essay.

Meanwhile, almost week by week, new evidence is produced by economic research confirming the basic contention of Nachtwey, Fratzscher et al, that a devastating shock was delivered to the German social model in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

III

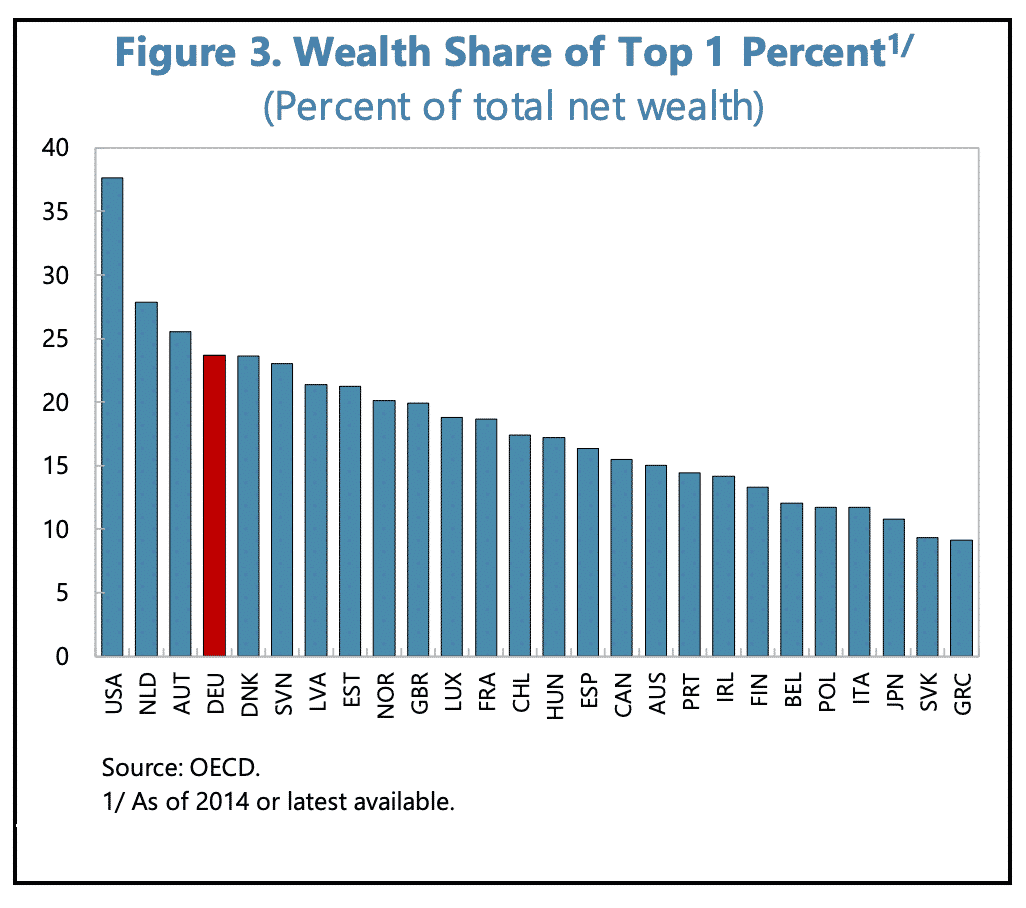

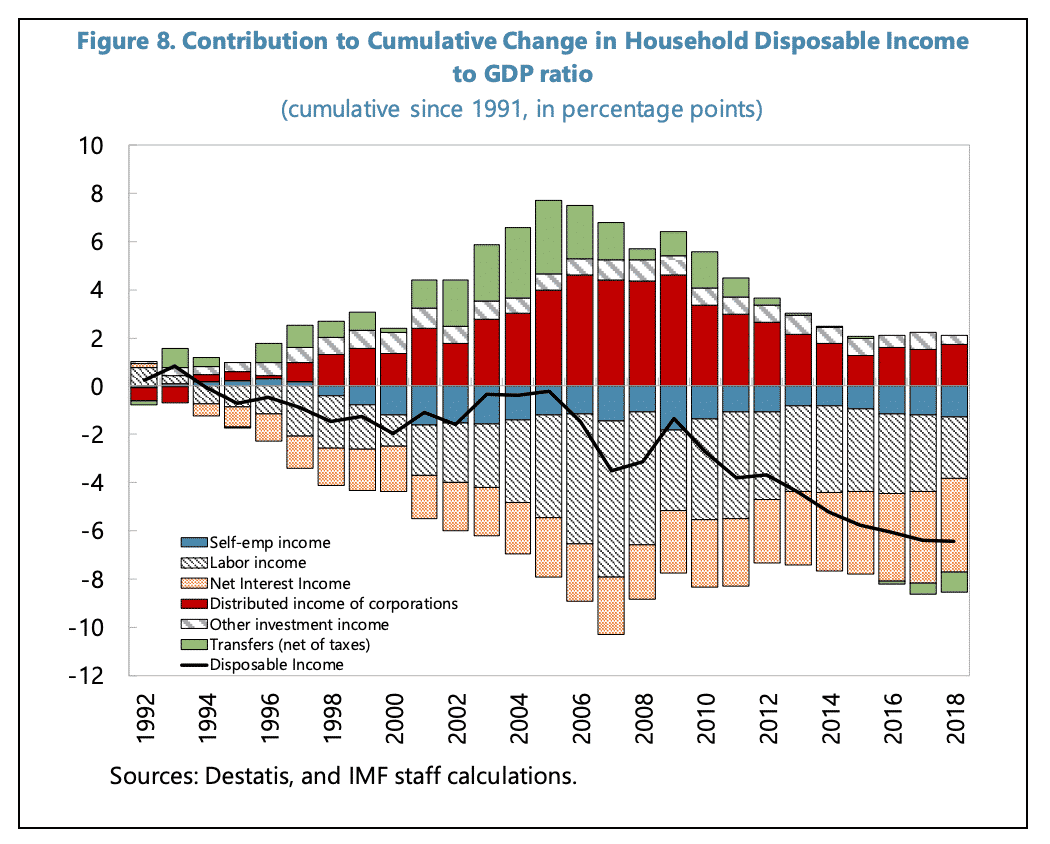

Most spectacularly the IMF in its recent Article IV consultation with Germany highlighted the connection between Germany’s surging inequality and its vast and destabilizing current account surplus. For ease of understanding the IMF even offers a handy flowchart illustrating the connection between inequality and macroeconomic imbalance.

Today, Germany runs a trade surplus which, in proportion to GDP, is far in excess of the levels achieved during the golden age of the “economic miracle”.

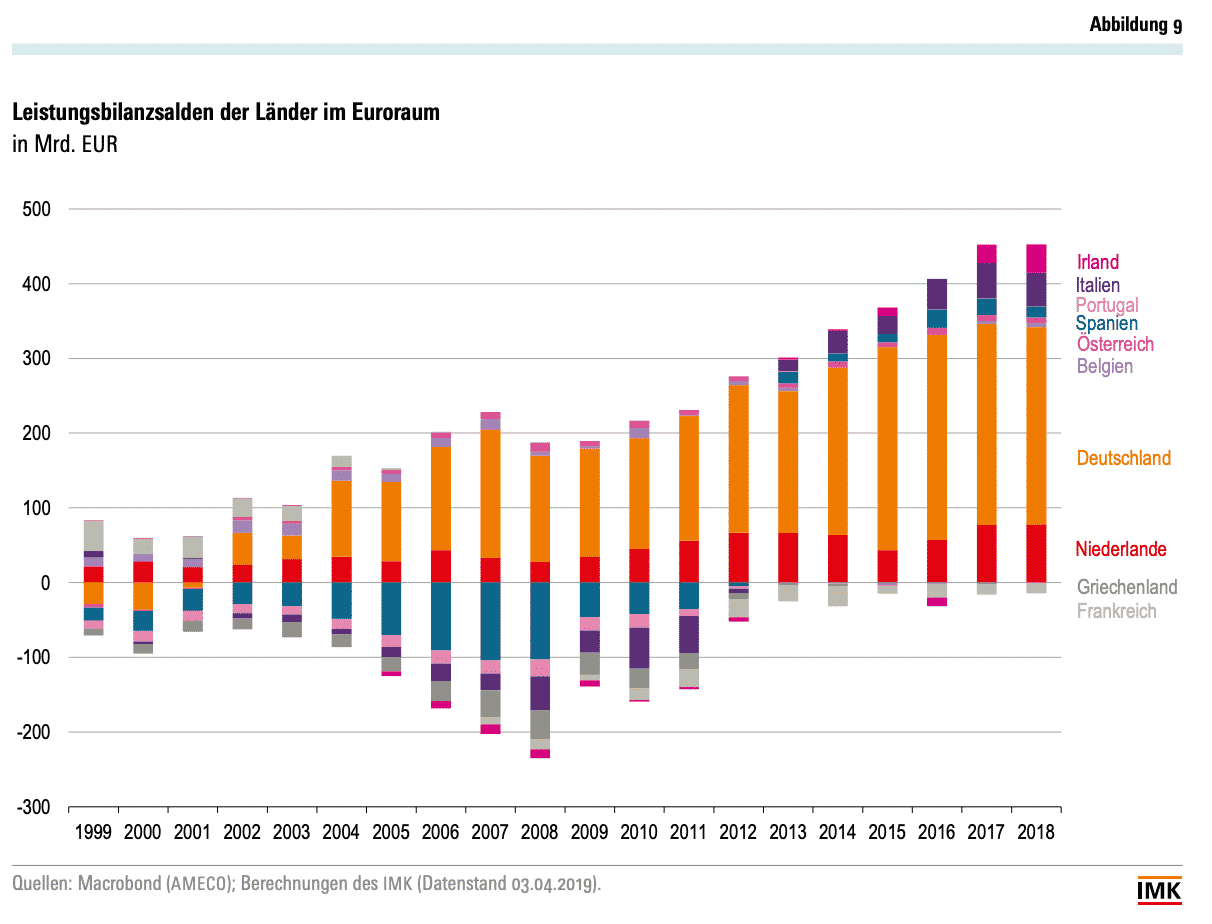

Here are Germany’s figures in European comparison from an excellent recent report by the IMK, the macroeconomic research institute of the German trade union movement, now headed by Sebastian Dullien.

And, as the IMF shows, the surge in that outsized current account surplus from the early 2000s onwards coincided with the surge in income inequality.

German inequality may not be at the levels we are familiar with in the US but the shift has been dramatic. And that shift coincides exactly with the period of the Red-Green government. It is not reducible to the Agenda 2010 program, but began already in the late 1990s with the dramatic weakening of trade union bargaining power.

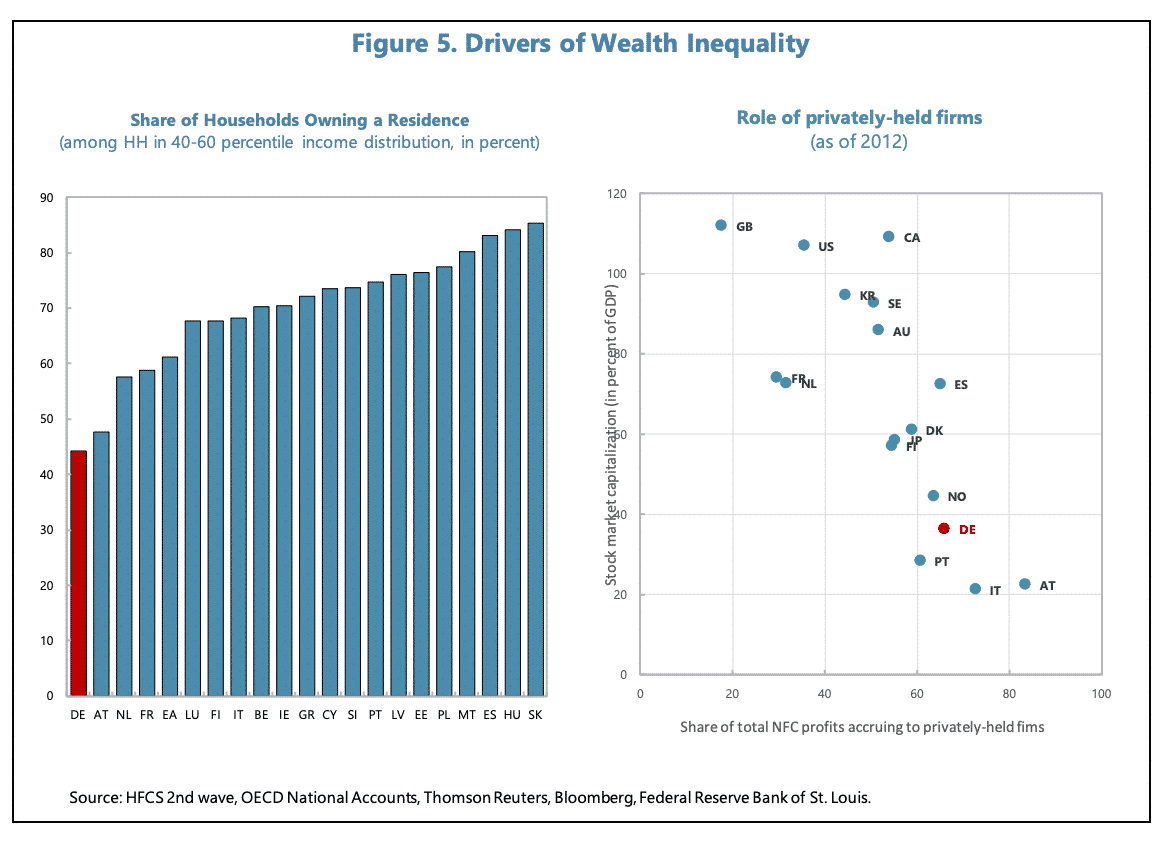

The one area where German inequality truly is stark is in wealth.

Not only does Germany have a cluster of immensely wealthy business owners, but the fact that the majority of the population still rent their homes rather than owning them means that there is relatively little wealth accumulation in the middle and upper middle class. Leveraged asset bubbles drive middle class and upper middle class accumulation in most other advanced economies.

To return to the shock of the early 2000s: as the IMF shows, it set in motion a dynamic which despite increasingly tight labour markets progressively squeezed the disposable income of German households. The shift in income from wages to profits and tax changes that discouraged the distribution of those profits lowered disposable income as a share of GDP between 2005 and 2017 by 6 percent.

In macroeconomic terms 6 percent of GDP is an enormous shift. Think almost twice the size of the defense budget in the US.

The shift in income away from households to the corporate sector has had a particularly dampening impact on consumption precisely because it has been concentrated on lower income households with a higher propensity to consume.

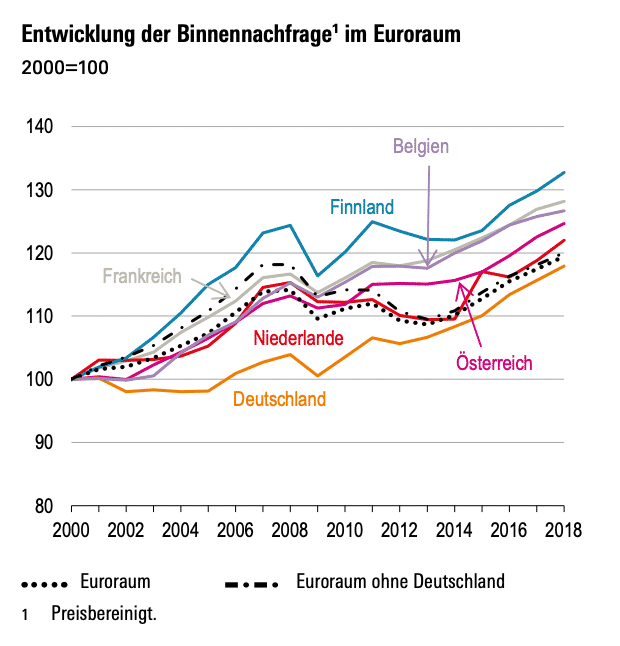

Lower consumption in turn translates into lower imports which helps to further increases Germany’s current account surplus. No one would worry about Germany’s buoyant exports if they were matched by equivalent imports. It is the chronic depression of German domestic demand (both consumption and investment) that is the cause of so much international criticism.

Here the IMK report offers a telling graph on German domestic demand.

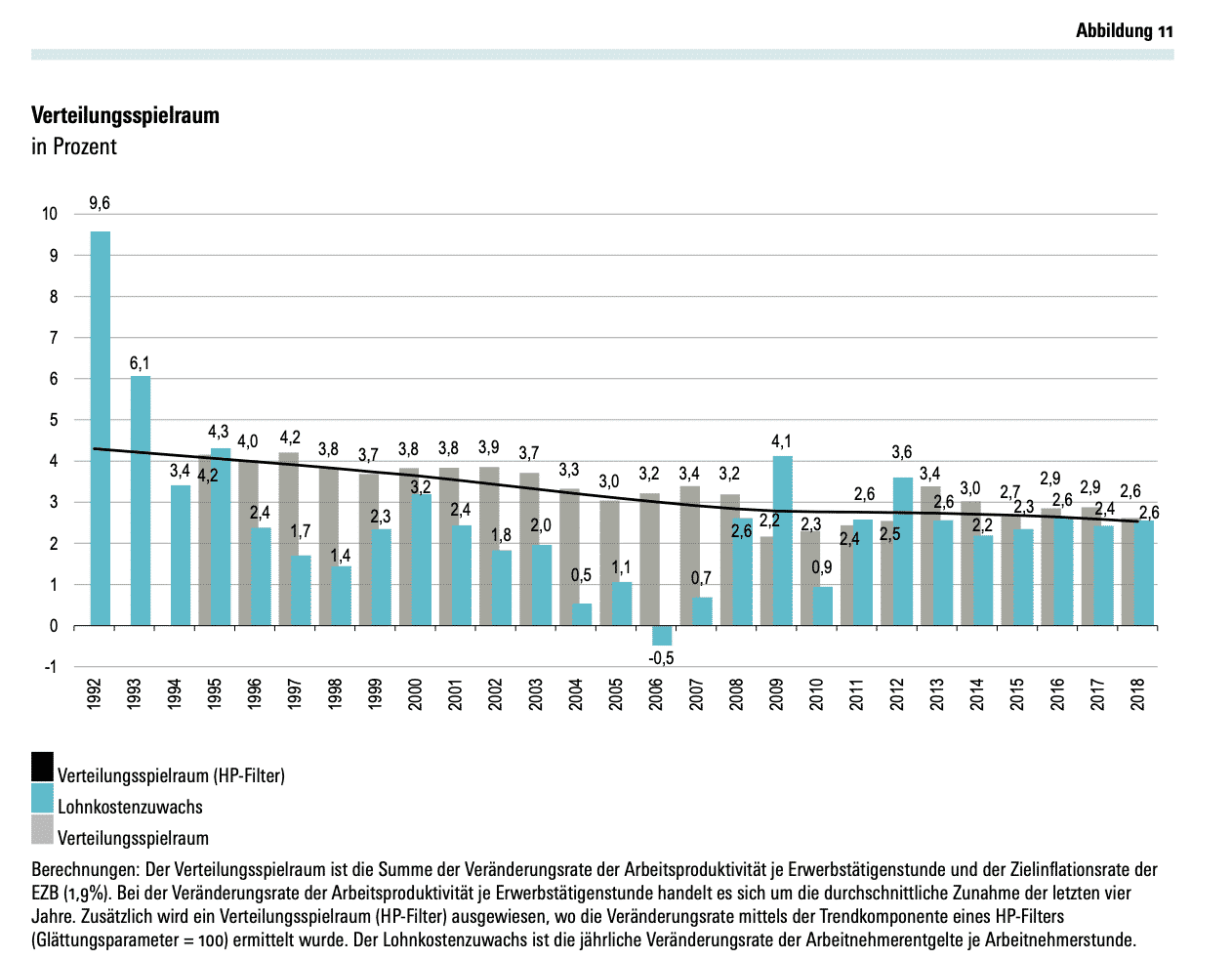

Viewed from the labour market side the IMK report, from which they really ought to produce an english-language slide pack, shows the persistent failure of German wages in the early 2000s to match productivity gains.

This produced a unit labour cost gap between Germany and the rest of the Eurozone which, more than a decade later, despite a few good years of wage growth in Germany, still has not closed.

Relative to 2000, Germany’s unit labour costs in 2018 were still slightly below those of Portugal after that country had suffered a decade of miserable recession.

IV

In diagnosing these imbalances, the economic side of the political economy, comes easily. To have this degree of consensus amongst all leading authorities is remarkable.

The IMF’s Article IV comments on the link between surging inequality and the outsized current account surplus surely warrants a response from the SPD-controlled Finance Ministry.

But the politics still leaves me scratching my head. I feel I need

(1) a thicker description of what happened in the Red-Green government that opened the door to Agenda 2010. Anke Hassel and Christof Schiller’s Der Fall Hartz IV is outstanding. I also found Gregor Schöllgen’s biography of Schröder illuminating. But I want more.

(2) a structural comparison of the three moments of radical centrism – in the early 80s, the early 2000s and in the 2013-15 – that have done so much to reshape the German political landscape. (I am bracketing reunification as sui generis)

(3) a clearer map of how the political complexity and the dramatic socio-economic shifts unleashed in the 2000s helped to frame and limit Germany’s semi-hegemony. I am still not convinced I understand the politics that drove/drive eurozone crisis management in Berlin.

(4) a better and more detailed grasp of how these same forces affect the profoundly disappointing course of Merkel’s Energiewende and Germany’s laggardly decarbonization.