Many of us had hoped that it would not come to this.

In Sunday’s elections in Italy, triggered by the premature fall of Mario Draghi’s government, the right-wing coalition of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, Matteo Salvini’s Lega and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli D’Italia, seem set to score a decisive victory. The center-left party PD is not polling badly. It will likely come in second in terms of share of the vote. But without an effective coalition, it is doomed to defeat.

Leading in the polls by a decisive margin are the Fratelli d’Italia, who emerged as champions of the hard-right from the fall of Berlusconi’s last government in the midst of the Eurozone crisis. Founded in December 2012, the Fratelli reconstitute what was once the neo-fascist movement. This traces its origins to the MSI, established in 1946 by survivors of Mussolini’s Salo Republic. In 2018 the Fratelli scored just 4.4 percent of the national vote. On Sunday they may well score six times that share. In the autumn of 2022, a hundred years on from the fascist seizure of power, Italy’s first woman Prime Minister is likely to be Giorgia Meloni, who in her youth hailed Mussolini as a great leader .

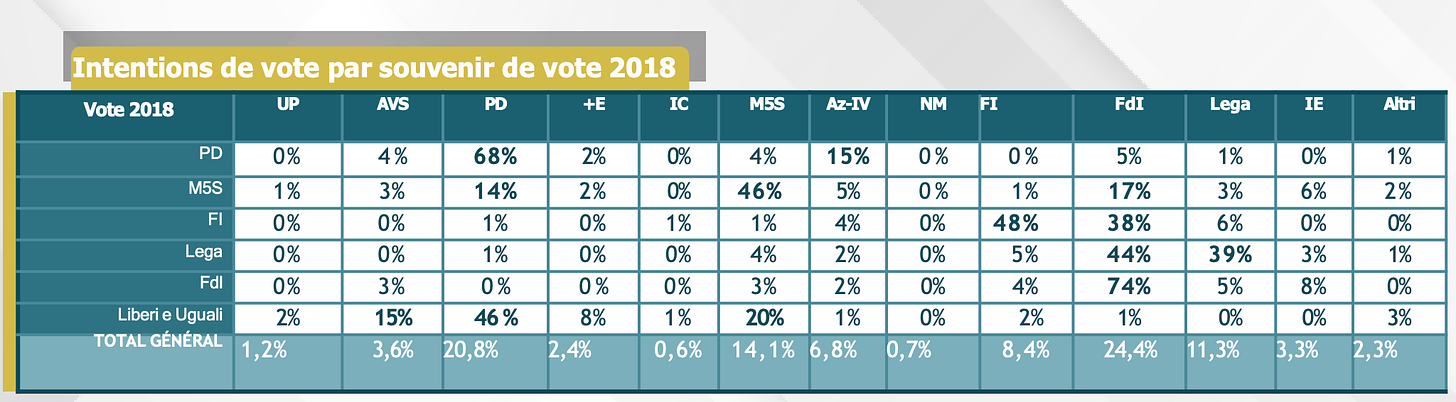

Compared to 2018 it seems that the Fratellli will gain their success largely by bleeding the electorates of the other conservative parties. According to the polls, they will likely take 44 percent of the vote cast for the Lega in 2018 and 38 percent of the Forza Italia vote. They will take a far smaller share from 5Star.

Source: Cluster17

5Star is bleeding voters in every direction, to the Fratelli but also to the PD.

Clearly, for many of us, the prospect of Meloni’s victory is a distressing one and it begs the question of who is voting for this party and why the center-left seems set to do so badly.

Recording the latest Ones and Tooze podcast on the upcoming Italian election, I realized that though there was plenty of analysis of the history of the Italian far-right and the figure of Giorgia Meloni, I had not seen any polling data in the English-language media showing us who was expected to vote for them, or any of the other contenders.

It is all very well to have the overall polling numbers, but to get a sense of what is actually motivating electoral currents you want to know how men and women of different ages in different parts of the country with different occupations, education and income level are going to vote.

Drawing a blank in the English-language media I put out a call on twitter and got a series of extremely useful replies from twitter friends. Thank you in particular to @tommsabb @ericvautier @jtbrowe @FulvioLorefice & @antoniofocella

****

A set of data from Corriera Della Sera paint the basic picture.

There are slight differences between women and men in party preference, with women slightly preferring the older parties of the right i.e. the Lega and Forza Italia. Men slightly prefer the PD and the Fratelli. But the big difference on gender lines is that a far larger share of women declare themselves undecided or uncertain about whether they will vote at all.

With regard to age it is striking that it is the center-left PD that does relatively well with the youngest voters. The PD also scores particularly well with those over 65, voters whose preferences were shaped before the break of 1992, when the Cold War party system collapsed. The prospective votes for 5Star are heavily weighted towards the youth vote. By contrast, Fratelli d’Italia does relatively poorly with both younger and older voters and concentrates its support amongst the middle-aged. This tendency is even more pronounced for the Lega.

On the educational axis a pattern emerges that is visible in many modern democracies and has been highlighted by Thomas Piketty. Amongst those with University degrees the center-Left PD will likely score more votes than the Fratelli and the Lega put together. Liberal progressive politics has become the domain above all of better educated Italian voters. The Fratelli achieve relatively similar support across all educational levels whereas the Lega sees a clear bias towards the lowest levels of qualification.

And this is confirmed when we look at occupational data. The center-left PD does best with the liberal professions, white-collar workers and teachers. It does badly with workers and the unemployed. The Lega vote is heavily tilted towards workers, whereas 5Star scores highly amongst the unemployed. What brings the Fratelli their likely success is that they do relatively well across all occupations, scoring poorly only amongst students.

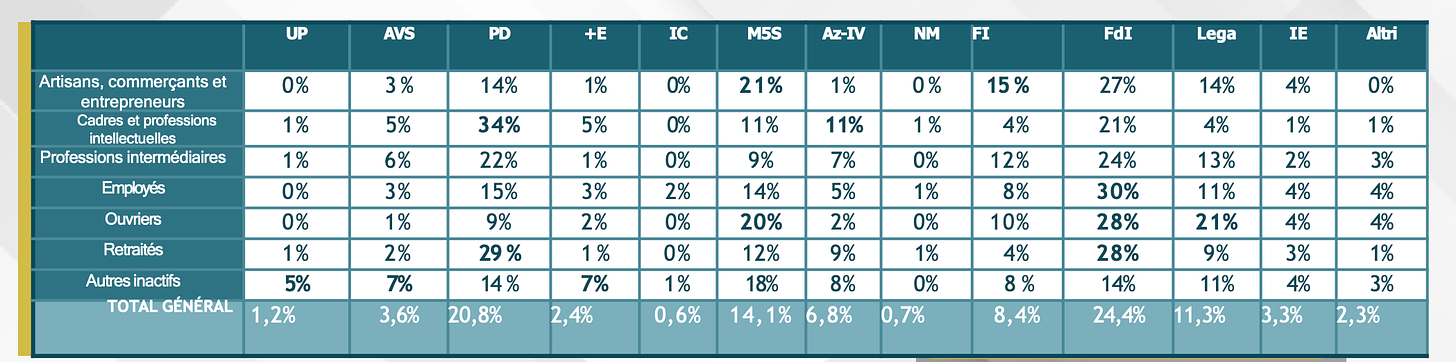

The social analysis group Cluster17 offers a slightly different breakdown of occupations, which highlights in even more stark form, the differences suggested by the Corriere data.

Source: Cluster17

According to Cluster17 the center left will score a miserable 9 percent amongst workers as against 29 percent amongst retirees and 34 percent amongst managerial and professional voters. The Lega reverses this pattern, scoring twice as well amongst workers as amongst the electorate at large. But it will be the Fratelli that will score the largest share of Italian working-class votes. Since workers make up 30 percent of the electorate this pattern strongly favors the right-wing coalition. All told the three-party right-wing coalition will likely capture 58 percent of Italian workers’s votes this year.

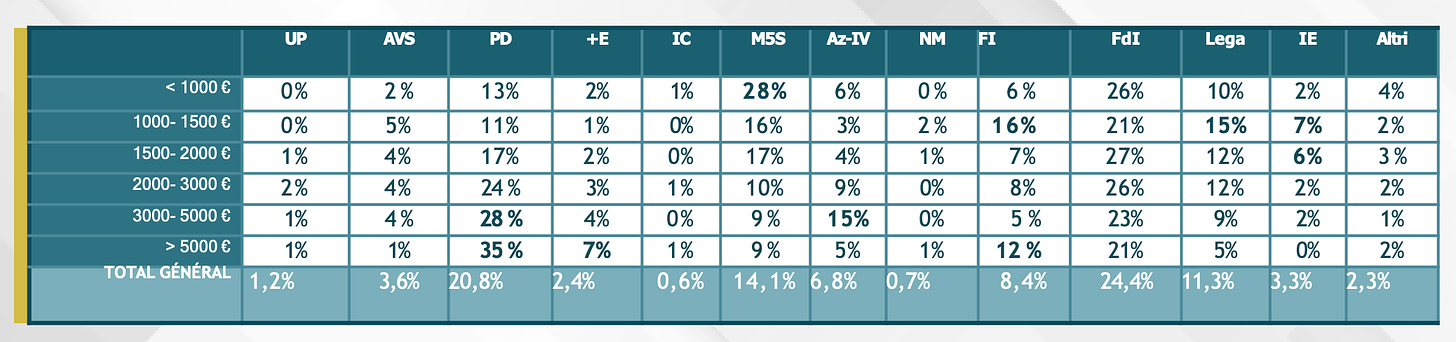

The pattern implied by the occupational data is strongly confirmed by data regarding income. Support for the center-left PD increases monotonously with income. Those on over 5000 euros per month are almost three times as likely to vote for the PD as those on under 1000. The reverse is true for 5Star. 5Star will likely take 28 percent of the lowest income group, twice its overall vote share. The Lega’s vote is strongest in the 1000-1500 bracket. Once again, the Fratelli stand out for the fact that their vote share varies relatively little across income classes.

Source: Cluster17

So, apart from not attracting the votes of students and pensioners, the occupational and income data do not really give us a clear view of the far-right Fratelli voters. Meloni who is herself from a working-class background and a tough suburb of Rome will do well with working-class voters, but that does not mean that she will do particularly badly with other social groups.

So what does motivate those who will cast their vote for the Fratelli? The answer is to be found most clearly on the side of culture and beliefs.

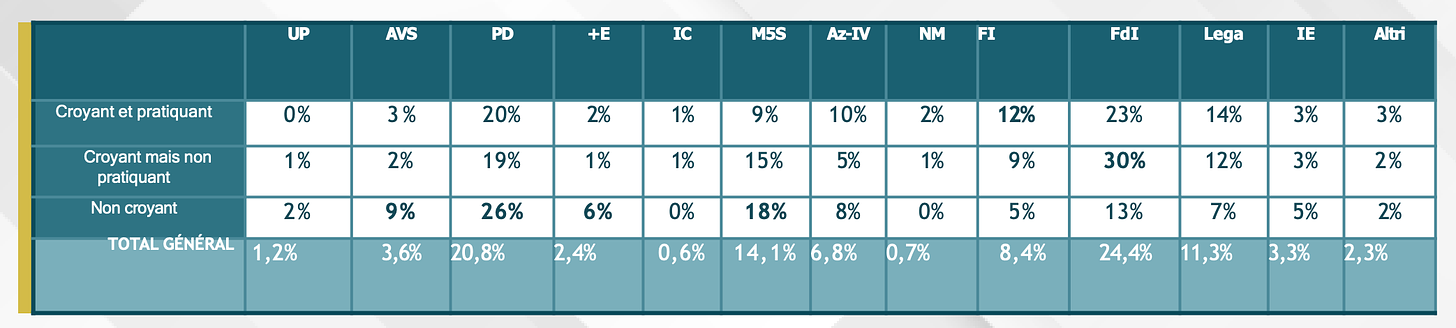

One fundamental divide within the Italian electorate is drawn on grounds of religion.

Source: Cluster17

Italy is a society in which a quarter define themselves as non-believers. 20 percent are practicing Catholics. And half identify with Catholicism but do not practice.

The Center-left scores by far the best amongst those who describe themselves as non-believers. 5 Star, likewise, does relatively well with non-believers (27 percent of the total). The Lega and Berlusconi’s Forza D’Italia do far better with practicing Catholics than with any other group. The Fratelli does best with those who declare themselves to be religious but are not practicing, which is also the largest segment of Italian society – 52 percent. Conversely, three of the right-wing coalition parties scores very poorly amongst the non-believers.

To dig deeper, Cluster17 divides the Italian population into a series of socio-cultural segments.

Source: Le Grand Continent

These groupings are defined by three different cleavages:

(1) Pro-migrant, pro-EU and anti-authoritarian v. voters who are anti-migrant, eurosceptic and authoritarian in cultural attitudes.

(2) Voters who favor or oppose redistribution between classes and between North and Southern Italy.

(3) Religious v. secular.

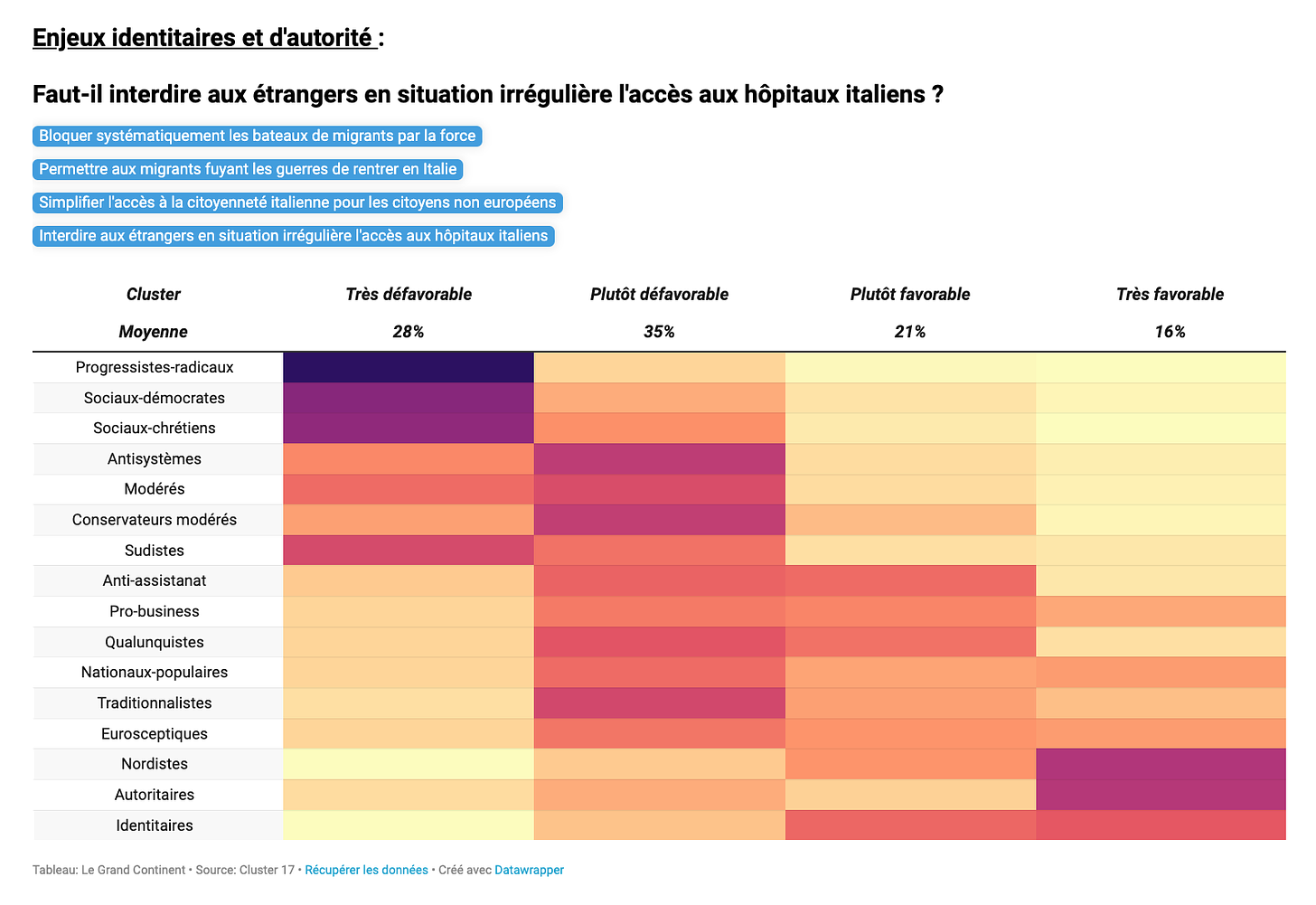

One can distinguish the different cluster of social and cultural attitudes by asking a series of questions, such as for instance: Should illegal immigrants be banned from access to Italian hospitals? This is a view that is popular with authoritarians and identitarians and opposed by progressive-radicals, but also by social catholics and social democrats.

Source: Le Grand Continent

What emerges from this elaborate exercise is an image of the kinds of social and cultural milieu which give their support to each of the Italian parties.

Source: Le Grand Continent

The upshot of this analysis it that the relative weakness of the left is due to the fact that it only appeals strongly to three social-cultural clusters: progressive-radicals, social democrats and social-christians. These groups tend to be older or younger, under-representing middle aged groups. They tend to be highly educated. The three bases of support for the PD are united in their opposition to identitarian policies, but are split on religion. The PD’s opposition to radical reform makes it difficult for them to capture any of the popular vote that is opposed to the identitarian politics of the right, but is attracted by the anti-systemic message offered by 5Star.

The strength of the Fratelli, by contrast, lies in their ability to mobilize support from 5 distinct conservative clusters ranging from moderate conservatives to identitarians and authoritarians (whose vote the Fratelli split with the Lega). Strikingly where the Fratelli score most strongly are not with modern radicals of the right, but with traditionalist. They also score heavily with anti-welfarists (anti-assistanat).

The upshot of this analysis is that the surge in support for the Fratelli does not mark a break with the pattern that was already established in 2018. The basic rearrangement of social identity and voting was already established in the decades since the end of the Cold War. By 2018 Italian workers had drifted into the right-wing camp. What Meloni has done is to take votes above all from her right-wing rivals and to bind together a wide range of right-wing and conservative opinion in a camp that refused any compromise with Draghi’s cross-party government. 5Star still takes a lot of the lower-income and youth vote that might otherwise be available to the left. That leaves the PD as a predominantly upper-middle class party that represents the educated and higher-income classes but has no chance of building a viable majority.

****

I love putting out the newsletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.